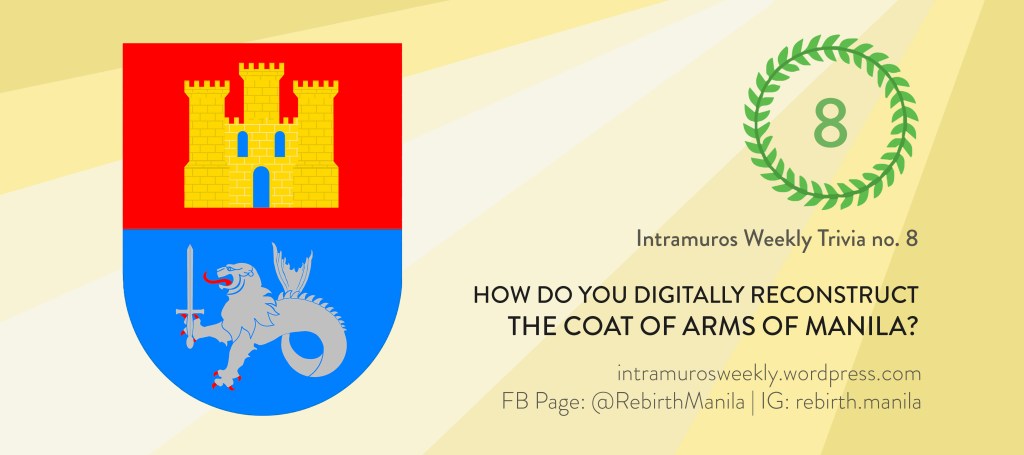

HOW DO YOU digitally reconstruct the original coat of arms of Manila?

By Rancho Arcilla

07 June 2020. Edited: 18 June 2020, 14.17

Branding is everything.

Digital art in this digital world is very important, and with the rise of the art of branding comes the need for exactitude, uniqueness, and consistency. Though anachronistic, it would be interesting to know how old brands can be recreated in new, modern, and digital methods–like say the original coat of arms of Manila.

For today’s Intramuros Weekly trivia (07 June 2020), we will do exactly that!

In a Royal Decree by Philip II, dated 20 March 1596, the City of Manila was officially “ennobled” when it was granted its own coat of arms. The blazon, as indicated in the decree, is roughly translated by Blair and Robertson as follows:

“…a shield which shall have in the center of its upper part a golden castle on a redfield, closed by a blue door and windows, and which shall be surmounted by a crown; and in the lower half on a blue field a half lion and half dolphin of silver, armed and langued gules–that is to say, with red nails and tongue. The said lion shall hold in his paw a sword with guard and hilt…”

The original text are as follows:

“…un eſcudo, en la mitad dèl à la parte ſuperior vn Castillo de oro en campo colorado, cerrado, puerta y ventanas de açul, y con vna Corona encima; y en la parte inferior en campoaçulmedio Leon, y el otro medio Delfin de plata, armado, y tan paſſado de guías, que es Vrias, y lengua de colorado, teniendo en ſu pata vna espada, con su guarnicion, y puño…”

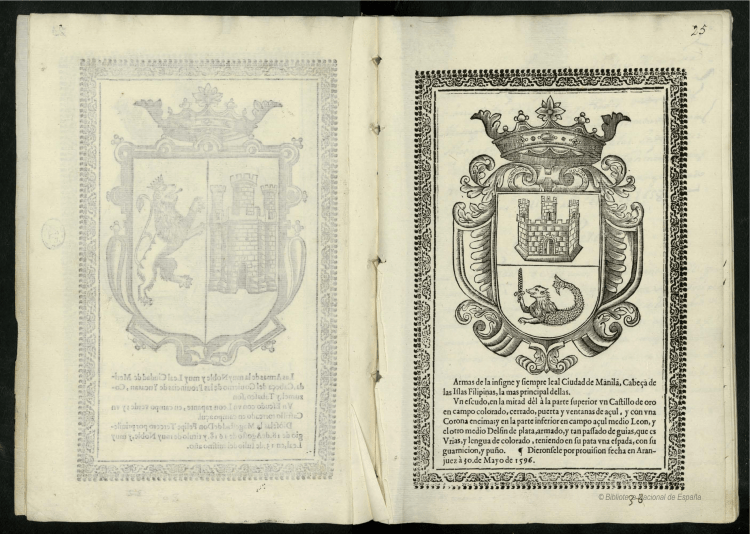

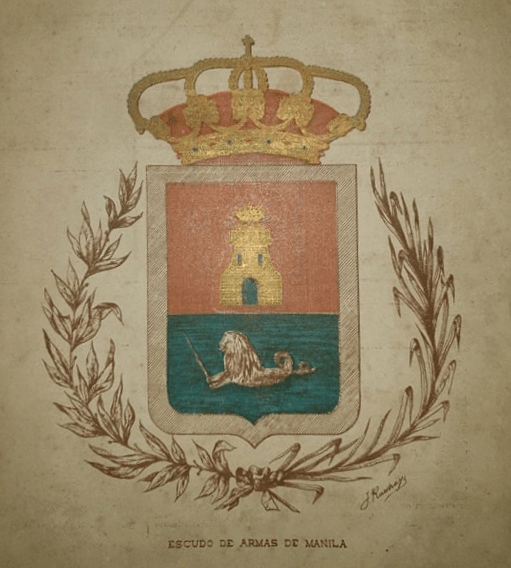

We suspect that the original illustration attached to the 1596 decree was lost, and to make up for this, Blair and Robertson attached an illustration from 1683, instead:

The most famous depiction of the coat of arms of Manila, however, is from the Noticias Civiles y Eclesiasticas de Indias (1654):

Other depictions also exist, such as in the Colección de Arms y Blasones de Indias (1767)

There are two problems: (1) None of these are contemporaneous with Philip II’s 1596 decree; and (2) none of them are colored, which is interesting given that the decree specifically instructed the use of vivid colors. With these limitations, how do we digitally recreate the Manila coat of arms as accurately and as precise as possible?

THE BLAZON

For those familiar with blazonry, this is not a problem. The first and most important concept in heraldry is the blazon. To put it simply, the essence of a traditional coat of arms is its blazon.

In modern times, the “logo,” as we all know now today, is guided by the “brand guideline.” Similar to the “brand guideline,” the “blazon” is the official, written description of armorial achievements which guides its depictions in drawings.

A coat of arms or arms is therefore primarily defined not by a picture but rather by the wording of its blazon. In recreating Manila’s original 1596 arms, you therefore do not necessarily need a picture as a guide; you just need to know the blazon. But of course, knowledge of basic heraldic customs also helps.

The grammar of blazonry is the set of rules and procedures concerning how blazonry are written and interpreted. This is a topic for another time, but for those interested, Bruce Miller (1988) is an interesting read. See references below.

So what can Manila’s 1596 blazon tell us?

THE TINCTURE (COLOR PALETTE)

In heraldic custom, colors are referred to as tinctures. The need to define tinctures is one of the most important aspect of blazonry.

The tinctures in Manila’s blazon, as translated by Blair and Robertson, are the following: gold (from “oro”), blue (form “açul”), red (from “colorado”), and silver (from “plata”). No other colors were used. However, blue, red, silver, and gold are not the correct jargons used in blazonry. It must be noted that Blair and Robertson were not exactly experts on European heraldic tradition, and their translation of Manila’s blazon should be scrutinized.

A bit of a background, the original coat of arms of Manila would have probably been created by the Cronista Rey de Armas of the Court of Philip II of Spain. The Cronista Rey de Armas, or the Chronicler King of Arms was a civil servant who had the authority to grant armorial bearings. Most countries at present have their own versions of the office of the Cronista. By way of analogy, in modern Philippines, for example, the some of functions of the Cronista are similar to the heraldic mandate of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, albeit with much less authority.

As such, for one to understand the tinctures used, translations should not be taken literally, considering Spain’s established heraldic customs. One has to consider the heraldic tradition that went with the process, and as such, certain nuances in tinctures must be established. For example, in European tradition, there are five basic tinctures, two metals, and two furs.

The five tinctures are as follows: Gules (red), Azure (blue), Vert (green), Sable (black), Purpure (purple). The two metals are: Or (gold), and Argent (silver). Meanwhile, the two furs are Ermine (with sable) and Vair (with azure)

The problem with Blair and Robertson’s translation is that blue (0000FF/0,0,255) is a different hue from azure (007FFF/0,127,255). While gules, or, and argent closely correspond to the modern red, gold, and silver, blue, as we know today, was not used in traditional heraldry. The use of blue (0000FF/0,0,255) would have been a mistake. To illustrate the difference:

As such, the correct tincture with the corresponding Hex, RGB, and CMYK are as follows:

For sake of simplicity for public, the rest of the article shall use the simple languages of red, gold, and silver, instead; except for blue, where we will continuously use azure in its place.

THE CHARGES (AKA SYMBOLS)

A charge is an emblem or device occupying an escutcheon (shield). Manila’s blazon has two charges: a castle made of gold (“oro”) and a sea-lion of silver (“plata”).

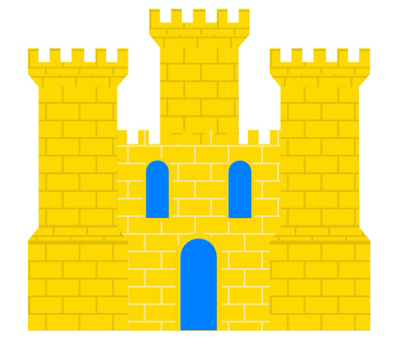

The Castle

The universal interpretation for the castle is that it was sourced from the arms of the Kingdom of Castile. This is most probably correct, since the blazonry of Castile is also gold and azure (Gules a triple-towered castle Or masoned Sable and ajoure Azure). Therefore, even if the blazon was silent on the number of towers, three are usually drawn in homage to the traditional arms of Castile, which has three towers as well. Note that the door and windows are indicated as azure (“açul”).

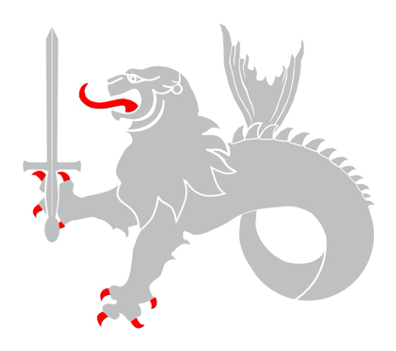

The Sea-Lion

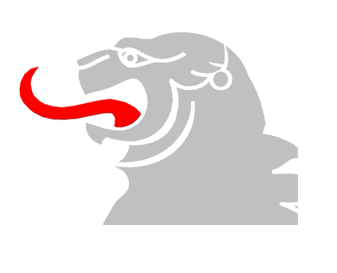

The silver (“plata”) sea lion, on the other hand, is merely described as half-lion (“medio leon”) and half-dolphin (“medio delfin”). In modern times, this is also known as the merlion. However, unlike most sea-lions in heraldic traditions, the sea-lion of Manila does not have webbed feet. The color of the claws and tongue (“lengue”) are in red (“Colorado”), while the silver sword (“eſpada”) has a guard (“guarnicion”) and a hilt (“puño”).

ESCUTCHEON

The Escutcheon, or the shape of the shield, was not indicated. The only wording used was “escudo,” which translates to “shield.” However, the “Iberian” style was traditional for Spanish arms. Following this heraldic custom, the correct shape of the Manila escutcheon is as depicted below:

CROWN

A crown (“corona”) was indicated by the blazon but no other descriptions were included. Depictions of the crown were therefore very liberal. The Noticias Civiles (1654) and the Colección de Armas (1767) ornamented their crowns with jewels and precious stones, most probably in reference to the symbolic crown of the King. However, in our digital recreation, we prefer a more simple crown so that we can refrain from using colors other than gold, the traditional color for crowns. With the design inspired from Noticias Civiles, sans heavy jewelry, here is what we came up with:

What Manila’s arms did not have

Important to note that Manila’s blazon only called for an escutcheon (shield) with charges and a crown–nothing more. However, in the case of the Noticias (1654), Collecion de Armas (1767), and Morga (1609), they added an elaborate stylized mantle surrounding the escutcheon. This is not part of the blazonry, but it does add some stylistic flair. For our digital recreation, we shall refrain from using other armorial achievements.

So how does a correct digital representation of Manila’s arms look like?

With everything considered, I was able to digitally create this piece which I hope would best give the original 1596 decree justice:

WHO GOT IT WRONG?

I can cite many, but for this Intramuros Weekly Trivia let us cite at least three.

The first would be the Manila coat of arms as depicted in wikipedia. While it got the red tongue right, it did not use the correct color of the claws and the hilt of the sword. Moreover, the hue of blue used is not azure.

Another case is from La Ilustración Filipina, dated January 21, 1894. In fairness to them I can not comment on the color since what I have is only a photograph, and besides, the colors used must have naturally faded over the years. However, what I can comment on are the charges. The castle, for one, has an unnecessary crown on top of it. Moreover, the Sea-Lion’s tongue and claws are not red.

Another one is from the Royal Postal Tour who shared a colorized version of the arms from the 1654 Noticias Civiles. The problem with this colorized print is that it got the colors wrong. Firstly, the field of the lion-dolphin is blue, not azure. Secondly, with regard to the charges, the doors and windows of the castle were incorrectly colored with gold, and the claws and tongue of the lion-dolphin are also incorrectly colored with silver.

Why does all of these matter? Because branding is important.

Manila’s status as the most important city during the Spanish colonial era is cemented by the fact that it was the only city granted and ennobled with the right to bear its own coat of arms. No other city in the Philippines has this historical status. Manila’s old arms was its unique brand and identity represented in paper and ink.

With the absence of the modern computer and printer, getting the right colors consistent all throughout would have been impossible. The blazon, being the essence of an armorial achievement, must therefore be respected. The sea-lion, for example, is a very common heraldic charge found in many European-styled armorial achievements. However, with the gorgeous manicured red claws and a vivid red tongue, Manila’s Sea-Lion becomes unique and easily separable from all other sea-lions. In branding, recognizability, integrity, value, and consistency are virtues which can never be dispensed of.

About the Author: Rancho Arcilla

John Paul Escandor Arcilla, known professionally as Rancho Arcilla, is the author of the Intramuros Register of Styles (2021). He served as Chairperson of the Intramuros Technical Committee on Architectural Standards (TCAS) from June 2022 to May 2024. As TCAS Chairperson, Arcilla oversaw the review of all development, including new constructions, in the Walled City.

Arcilla was also the first Archivist of the Intramuros Administration. With mandate from Atty. Guiller Asido, Administrator of Intramuros from 2017 to 2022, Arcilla established the Administration’s Archives and Central Records Section, serving as its first Section Head from July 2019 to June 2024.

He has an MA in Philippine Studies from UP Diliman and a BA in Asian Studies from the University of Santo Tomas. Arcilla specializes on colonial architecture. In 2021, Arcilla was instrumental in the development of the Revised 2021 Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of Presidential Decree No. 1616, the main framework and legal instrument in the management of Intramuros District. The architectural provisions of the IRR and the Intramuros Register of Styles (2021) is based on his MA thesis Walls within Walls: The Architecture of Intramuros (2021).

References

Biblioteca Nacional de Espana (nd). Noticias civiles y eclesiásticas de Indias y otros documentos [Manuscrito]. Retrieved form bi t. Ly /3cOzl2z

Biblioteca Nacional de Espana (nd). Colección de armas y blasones de Indias [Manuscrito]. Retrieved from bi t. ly /2XOkSzg

Blair, Emma Helen, ed. (1911) The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803. Retrieved from bi t .ly/ 2AlW2xX

Elementhree (2018 Dec 10). What to Include in Your Brand Guidelines [Walkthrough]. Retrieved from bi t. ly/ 3fewx0r

Encyclopaedia Britannica (nd). The nature and origins of heraldic terminology. Retrieved from Bi t. ly/ 3fbG2xf

English Heritage (nd). A Beginner’s Guide to Heraldry. Retrieved from bi t. ly/ 2BUFYUj

Fleur de Lis Designs (nd). Heraldry and the Parts of a Coat of Arms. Retrieved from bi t. ly/ 2YAirQn

Miller, Bruce (1988). Master Bruce’s Guide to Excruciatingly Correct Blazon. Retrieved from bi t. ly/ 3d9J4Az

Presidential Museum and Library (nd). The Ancient Archipelagic Ultramar: Symbol of Manila, the Presidency, and the Philippines. Retrieved from bi t. ly/ 2AlX9O9

Royal Postal Tour (2013 Sep 2). Retrieved from bit. ly/ 2XMO4qt

Brought to you by Renacimiento de Manila

Leave a comment