The Bahay na Bato Styles of Manila

Rancho Arcilla

14 June 2020

Geographically being located at the crossroads of civilization and by virtue of being part of the regional maritime trade work of Southeast Asia, the development of architecture in the Philippines is a reflection of thousands of years of acculturation, adaptation, and innovation. The vernacular (or pre-colonial) style, as encapsulated in the quintessential Bahay Kubo (cube house)is a reflection of Austronesian heritage, while the colonial style, as symbolized by churches and the classic Bahay na Bato (stone house) illustrate the complex interlacing or of opposing cultures and the unique adaptation and interpretation of western tastes, styles, and innovation in a tropical setting.

In their book Ancestral Houses of the Philippines (1981) Fernando Zialcita and Martin Tinio were probably the first to comprehensively and intensively discuss about Spanish colonial era residential spaces. Zialcita and Tinio traced the Bahay na Bato from the Bahay Kubo, which in turn was connected to an overall nascent Austronesian architectural heritage of houses on stilts. The authors posit that structures in Manila during the early years of Spanish occupation resembled peninsular and Latin-American constructions, however as earthquakes, fires, and wars repeatedly ravaged the city over the years, the type of architecture resilient to all of these eventually returned back the quintessential Bahay Kubo, thus, in the later half of the Spanish regime, the Bahay na Bato, the “all weather house”was born. This architectural evolution, the authors suggests, started with Manila and eventually spread to the rest of the provinces of the Philippines as far away as Batanes in the North, albeit with contextual environmental adaptations.

However there is a misnomer on the term Bahay na Bato. Firstly, it is not necessarily made of stone. The “bato” in Bahay na Bato is a actually a misnomer as the stone used is merely an accessory—a “curtain” if you will. In reality it’s the wooden posts that hold everything up. Secondly, it is not necessarily residential. As the “All Weather House,” it housed not only the family; it also housed heavy industry (such as in the case of the Sunico foundry), educational institutions (such as UST, Ateneo, San Jose, among others), military installations (such as Fort Santiago), cigar factories, warehousing, and other non-residential uses.

ISTILONG QUIAPO

As with his 1981 book, Zialcita made another groundbreaking work with his unpublished manuscript ISTILONG QUIAPO. Together with Erik Akpedonu, they are perhaps the first to attempt to discuss different styles under the Manila Bahay na Bato type. With Quiapo as compass, the authors were able to nuance a total of 8 different styles:

- Flowers in Trellis Style;

- Horizontals and Verticals Style;

- Platter Style;

- Board and Batten Style;

- Quadrant Style

- Straight and Narrow Style; and

- Liberation Style.

Important to note, however, the these styles are reflective of the Manila urban setting, and provincial styles were in not included. In some cases, however, Quiapo/Manila styles can sometimes also be seen in the provincial setup. This is an article for another time.

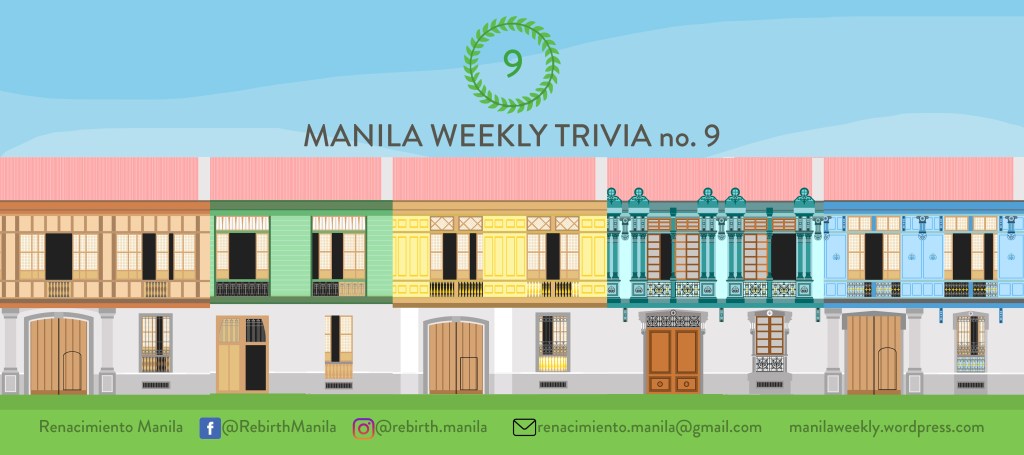

In this article we shall be discussing only four of these styles, namely: Flowers in Trellis, Horizontals and Verticals, Platter, and Board and Batten.

The Four Basic Styles

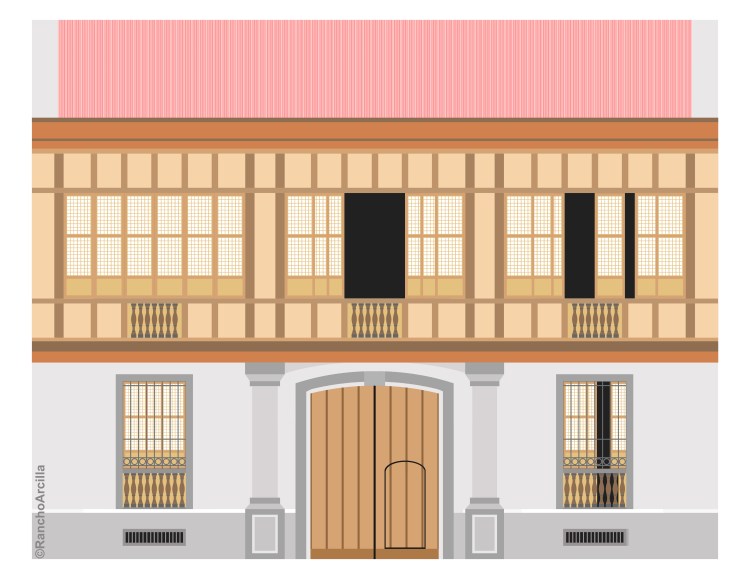

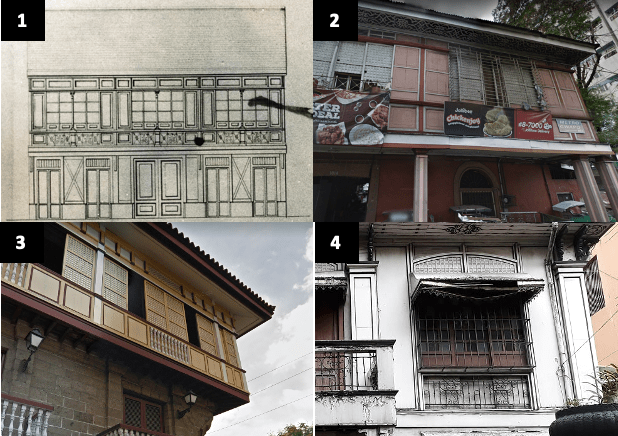

BOARD AND BATTEN STYLE

Prevalence: Manila, Mid 19th Century to 1880s.

The Board and Batten is the oldest Bahay na Bato style. Arguably speaking, this was how the Bahay na Bato type might have started in Manila. As what was suggested earlier, structures in Manila during the early years of the Spanish regime resembled peninsular and Latin-American constructions; however as earthquakes, fires, and wars repeatedly ravaged the city over the years, the type of architecture resilient to all of these eventually returned back the quintessential Bahay Kubo, thus, in the later half of the Spanish regime, the Bahay na Bato, the “All-Weather House” was born. It is assumed that when this “All-Weather House” was born, it took the form of the Board and Batten.

The Board and Batten Style is characterized by the manner on how the wall of the second-story was constructed. Board and batten, or board-and-batten siding, describes a type of exterior siding or interior paneling that has alternating wide boards and narrow wooden strips, called “battens.”

Aesthetically speaking, the exterior of a Board and Batten Styled house is simple and almost devoid of decorative elements. They tend to have no ventanillas at all, and for the few that have, they’re usually very small when contrasted against the entire length of the windows. With evolving tastes and changing trends, this style was prevalent until the 1880s when it was superseded in popularity by the Platter Style.

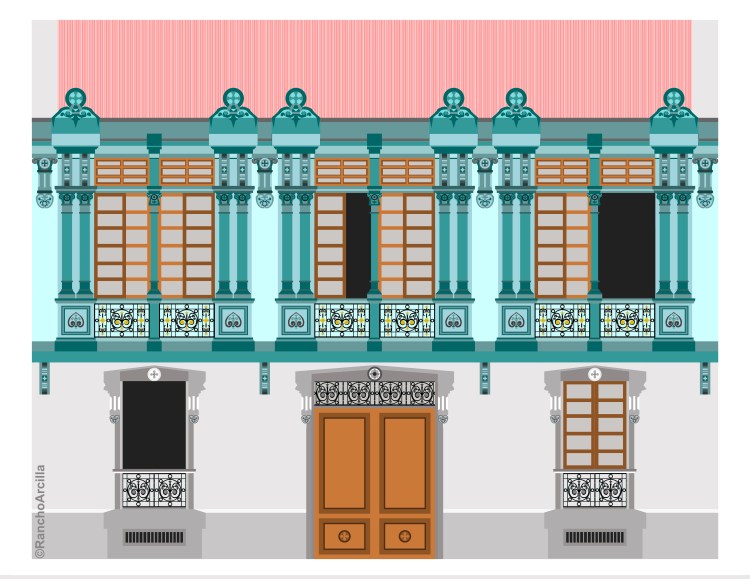

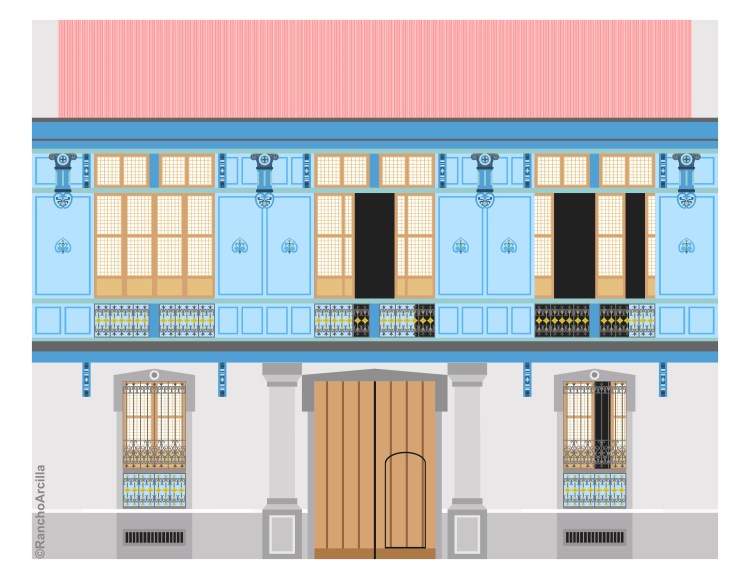

Flowers in Trellis Style (Bulaklak sa Trellis)

Prevalence: Manila, 1890s

Of all the basic styles, the Flowers in Trellis was the most elaborate, and if the Philippines had its own version of the Rococo, this would be it. As what the name suggests, Zialcita likened this style to flowers hanging from a garden trellis or net (see image below). Common motifs and design ideas include flowers, acanthus leaves, fruits, vegetables, and sometimes animals. Every space is ornamented, even the roof–such as in the case of the Teotico House which sported exquisite flower-themed acroterias (acroterion).

Decorative grills are are noteworthy in Flowers in Trellis styled houses. A common theme was the abaniko, a type of hand-held fan which in itself mimics the shape of the anahaw leaf.

The brackets supporting the second floor overhang were usually highly ornamented as well. Vegetables such as pumpkins may sometimes be seen hanging in some of them.

The style peaked in the 1890s but as an architectural fad it did not last long, however, and only a few of them remain today. Examples of extant structures following the Flowers in Trellis are found in Quiapo and Bataan–such as the Teotico House along Barbosa St., and the three-story Casa Bisantina at Las Casa Filipinas de Acuzar, a theme-park and beach resort in Bataan.

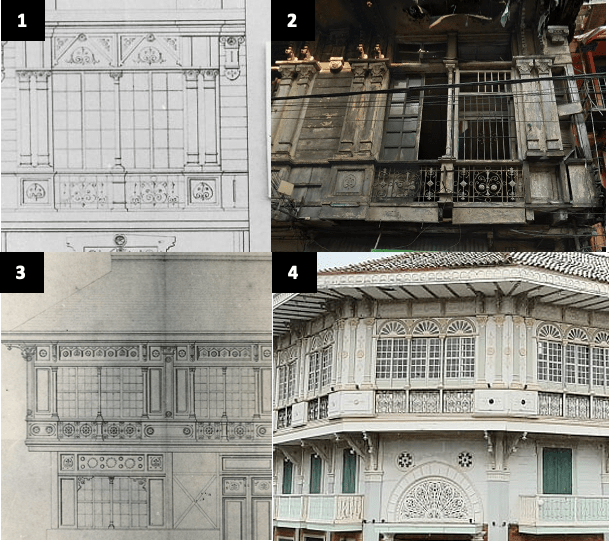

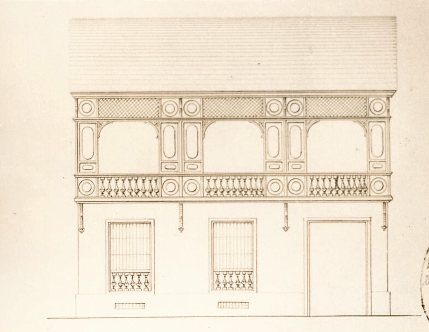

Platter Style (De Bandehado)

Prevalence: Manila, 1880s – mid 1940s

One can find a little bit of humor in comparing Flowers and Trellis with the Platter Style. For one, while Flowers in Trellis was named after flowers hanging from a garden trellis; the Platter Style, on the other hand, is named by Ziacita after dishes, specifically large plates or platters–the same items used to serve food in dinners.

Simply put, Platter styled houses are typified by “platter designs,” as if one is purposely hanging dinner plates in the exterior walls of one’s house. While the rectangular platter was the most common, some houses had circular platters as well.

This kitchen-themed style was the most flexible as well. While some houses such as the Santiago House in Quiapo exhibit almost purely the Platter Style, most of the houses using this design usually combine it with other styles as well, such as the Flowers in Trellis.

Being very flexible, the Platter Style was the most common Bahay na Bato style in Colonial Manila. Its prevalence lasted from the 1880s, from the decline of the Board and Batten, to the start of World War II in the mid 1940s. The Second World War effectively ended the “Platter era” in Bahay na Bato constructions.

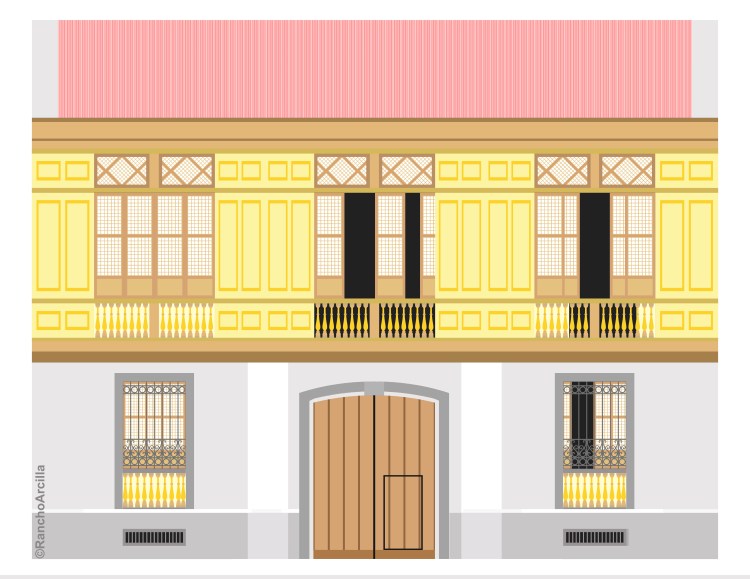

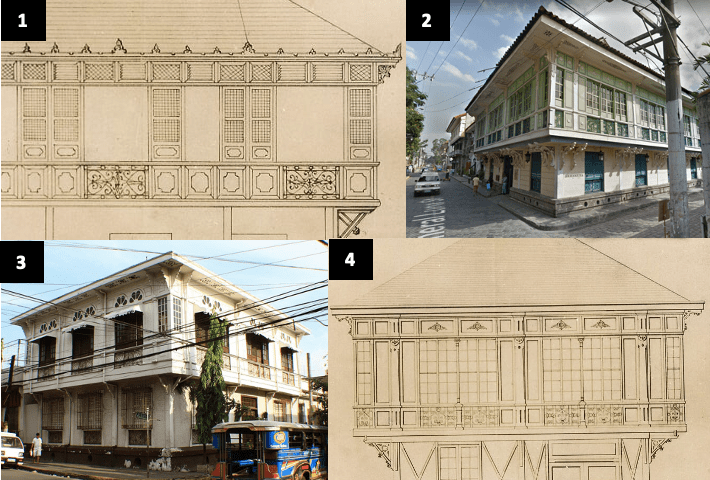

Horizontals and Verticals

Prevalence: Manila, 1900s-1940s

The Horizontals and Verticals Style was the most “modern” of the basic styles. Modern in the sense that it emerged the latest (early 1900s) and was also the most aesthetically devoid.

The use of wooden horizontal panels running the entire length of the exterior is not new, as the Flowers in Trellis sometimes utilized this. However, in the Horizontals and Verticals Style, this design was most pronounced. As the name suggests, it was characterized by the contrasting vertical lines and horizontal lines made from the lines of the wooden boards running horizontally the entire length of the facade versus the vertical lines of the windows which run the entire height of the second story. This horizontal-vertical contrast was made possible with the absence of decorative elements.

The post-war era signaled the beginning of frugality, simplicity, and modernity. The Horizontals and Verticals, being the simplest of them all, managed to continue to the post-war era, albeit in a new form: the Liberation Style.

This style, however, is a topic for another time, but for one to visualize the Liberation Style, one simply need to remove the ventanillas and the espejos from the Horizontal and Vertical Style. However, with the absence of these vertical elements, the Horizontals and Verticals Style ceased to be, and in its place the Liberation Style emerged.

Some notes on the architecture of Quiapo and Intramuros in the 19th Century

Apart from both being bordered by the Pasig River, the heritage and cultural treasures of Intramuros and Quiapo share many interesting similarities. While it is indeed true that the present dominant character of Quiapo has become deeply religious in nature while that of Intramuros to an antiquated Spanish-period one, these two districts have a long way to go when one untangles the surface and explore the history and art of these two historic centers.

Historically, both Intramuros and Quiapo derive their names from aquatic plants. The place name “Quiapo” was named after a plant species of the same name that abounded its estuaries, while Intramuros—whose original name was “Manila”—was derived from the plant “Nilad,” which filled the Pasig River.

And it is with Manila’s tropical climate where these plants abounded that typified human settlement. The warm and humid climate coupled with the common occurrences of devastating earthquakes throughout the Spanish era brought about the development of the Bahay na Bato architecture—the stone ground floor, usually made of Adobe from nearby Guadalupe, provides the foundation and sturdiness of the building; while the wooden second floor gives the structure both good ventilation and flexibility.

The Bahay Na Bato, a product of centuries of architectural adaptation, is of course a common architectural feature across the colonial Philippines, but what sets Intramuros apart is its unique urban landscape and social context—the congestion within the enclosure of the walls restricted horizontal growth, giving rise to elaborate courtyards to compensate for lost open spaces; while the significance of Intramuros as the political nucleus of the Spanish East Indies made it the neighborhood of the most exalted altas sociedades or elites of the colonial society.

The later-half of the 19th Century, however, saw the gradual outward migration of the elites from the congested Walled City, bringing with them their architectural tastes and ideas of what a house for fit for the wealthy should look like. It is during this time that we see the likes of the Ayalas, Hidalgos, Zaragozas, Padillas, Paternos, Ocampos and Tuazons resettling in the tranquil and then spacious land of Quiapo, with its then serene esteros and fertile soil. What made Quiapo even more ideal is its relative proximity with Intramuros which, until the early 20th Century, was the center of political and religious life in Colonial Society. This may very well explain the architectural similarity of Quiapo and Intramuros during the 19th Century: Quiapo as a new neighborhood for the rich carried with it similar designs from the residences of the old Intramuros.

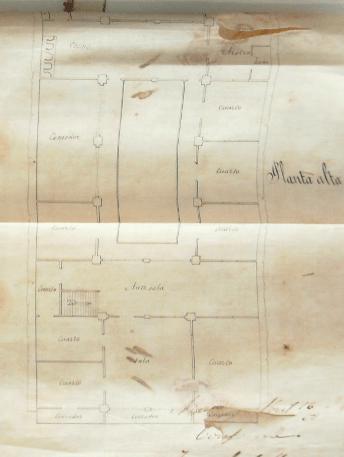

The Courtyard and the Lack of Setback

Although Quiapo is less congested and lacked a wall enclosure, archival drawings show that both of them have strikingly similar schematics in terms of elaborate and spacious courtyards and lack of setbacks —quite ironic for the spaciousness of Quiapo. The courtyard aspect is specifically noteworthy, because while Intramuros and Quiapo share this attribute in abundance, we find that this feature is relatively very uncommon in other districts such as Santa Cruz, Tondo, or Ermita.

The similarity of Intramuros and Quiapo in terms of architecture is made even more interesting given that the structures found in other nearby centers such as Santa Cruz, San Miguel and Binondo have developed into something distinctly different. The development of the bahay na bato of Binondo and Santa Cruz are deeply influenced by their respective centers’ deeply commercial character—something that both Intramuros and Quiapo lacked; while the very rural character of San Miguel made it ideal for summer mansions, such as the Summer Palace of the Governor General (Malacanang).

World War II, however, erased the last remains of Intramuros’ last remaining vestiges of the past, but with Quiapo relatively untouched by war, perhaps the still existing bahay na bato mansions of the Paternos, Santiagos, Padillas, and Zamoras along Hidalgo Street can still serve as examples of how houses used to look like, not just in Quipao, but also in Intramuros.

About the Author: Rancho Arcilla

John Paul Escandor Arcilla, known professionally as Rancho Arcilla, is the author of the Intramuros Register of Styles (2021). He served as Chairperson of the Intramuros Technical Committee on Architectural Standards (TCAS) from June 2022 to May 2024. As TCAS Chairperson, Arcilla oversaw the review of all development, including new constructions, in the Walled City.

Arcilla was also the first Archivist of the Intramuros Administration. With mandate from Atty. Guiller Asido, Administrator of Intramuros from 2017 to 2022, Arcilla established the Administration’s Archives and Central Records Section, serving as its first Section Head from July 2019 to June 2024.

He has an MA in Philippine Studies from UP Diliman and a BA in Asian Studies from the University of Santo Tomas. Arcilla specializes on colonial architecture. In 2021, Arcilla was instrumental in the development of the Revised 2021 Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of Presidential Decree No. 1616, the main framework and legal instrument in the management of Intramuros District. The architectural provisions of the IRR and the Intramuros Register of Styles (2021) is based on his MA thesis Walls within Walls: The Architecture of Intramuros (2021).

Leave a comment