By Beatrice Ann Dolores

21 June 2020

The arquitectura mestiza, also known as “Ancestral House” or “bahay-na-bato” in the Philippines, not only is an evolution of the bahay kubo through its building materials used but also in transcending the essence of a Filipino’s characteristics and how it gave importance to nature through its design. Its design also took into great consideration the safety and wellbeing of its users. This is mainly exemplified by its two most notable features: the stone ground floor and the elevated wooden quarters.

The stone ground floor upgraded the elevated stilts of bahay kubo to withstand earthquake yet still protect the occupants from the seasonal flooding. Aside from keeping the occupants dry from seasonal flooding, the living quarters are strategically elevated to catch the winds which are stronger at higher elevations (Zialcita & Tinio, 1980). Together with the wide system of windows which stretch from one end to another and its generous space indoors, natural ventilation is utilized and thermal comfort is optimal despite the nonexistence of electricity during the Spanish colonial period. It also made sense back then that large living spaces were provided because of the large number of family members they used to have.

To reduce heat gain and to serve as buffer from the elevated living quarters, some houses have an extended surrounding portion called volada. There is also an elaborate system of fenestration which optimize and allow the users to alter the openings in whichever they please.

This is done mainly through the broad and grooved window sill that holds two sets of sliding shutters: a set of capiz or oyster shell shutters, and a set of louvered shutters (Reyes, 2013). The users then have control with the amount of daylight, heat, view and wind they will allow inside the dwelling. Between the window sill and the floor runs the ventanilla, also with its own sliding wooden shutters and iron grills or wooden balusters as protective barrier. This also allows more airflow and light coming from the floor height to the window sill unlike conventional exterior façades. (Zialcita & Tinio, 1980). These openings around the building envelope are assisted by the fenestrations within the building like the wide double doors and wall partition panels (also known as calado) to keep the air flowing from one space to another without the use of electricity.

The wide windows also allowed more view of the dwelling’s surroundings which include nature, their neighbors, and down the streets which is most beneficial in times of cultural activities like religious processions. Those wide windows from one end to another allow the numerous members of the household to all have a chance to view the streets without any obstructions. The young ones are also given the accessibility to see using the ventanilla or “little window” while being safely protected by its grills or balusters. Children also sleep beside their little window every siesta (afternoon naps) to take in the cool, afternoon breezes (Zialcita & Tinio, 1980). All these show how everyone in the family is given consideration in the design of the building even at their simplest activities.

Wide open spaces of the structure seem to flow from one room to another, providing a spacious and welcoming atmosphere to its inhabitants. The house’s stretch of windows let the dwellers have an authentic connection to nature because of its how open it is to the surrounding environment. The inter-connectivity, wide spaces and windows not only address thermal comfort and spaciousness, they also allow outdoor interactions with their neighbors and the activities happening down the streets. These special features translate the notable characteristics of a Filipino into this architectural design: family-oriented, hospitable, and being on with the community. (Zialcita & Tinio, 1980).

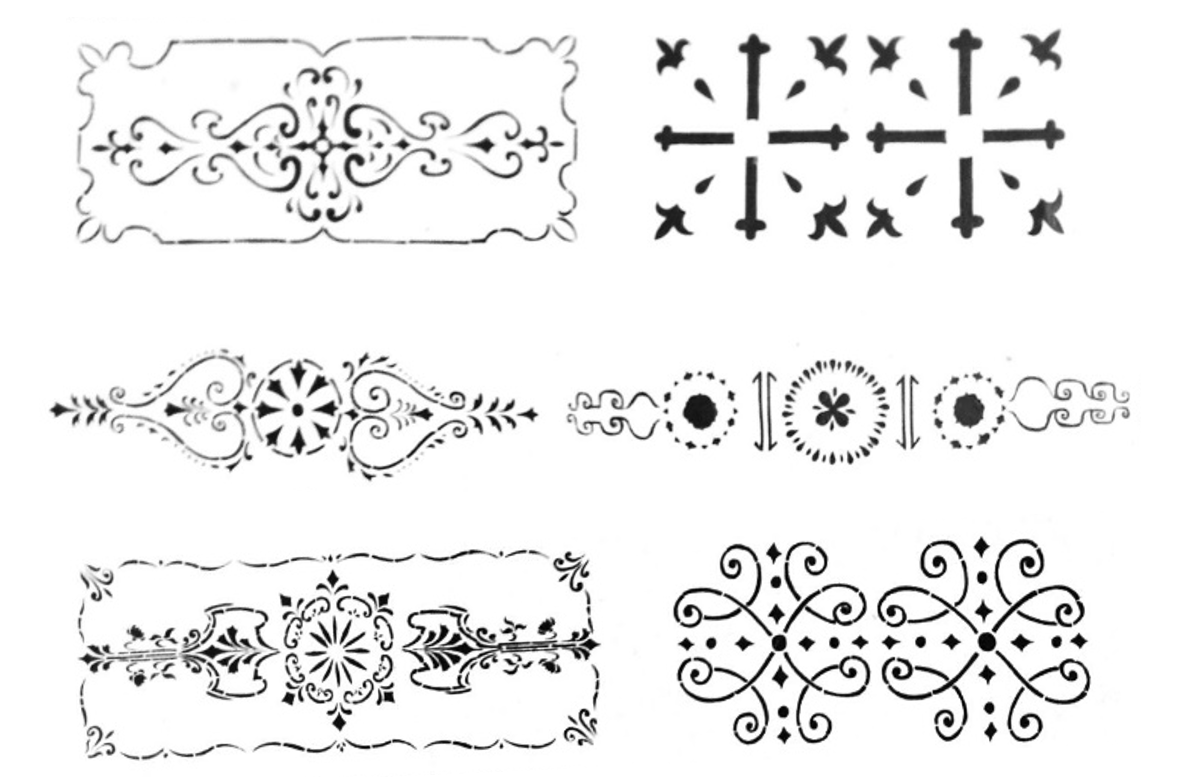

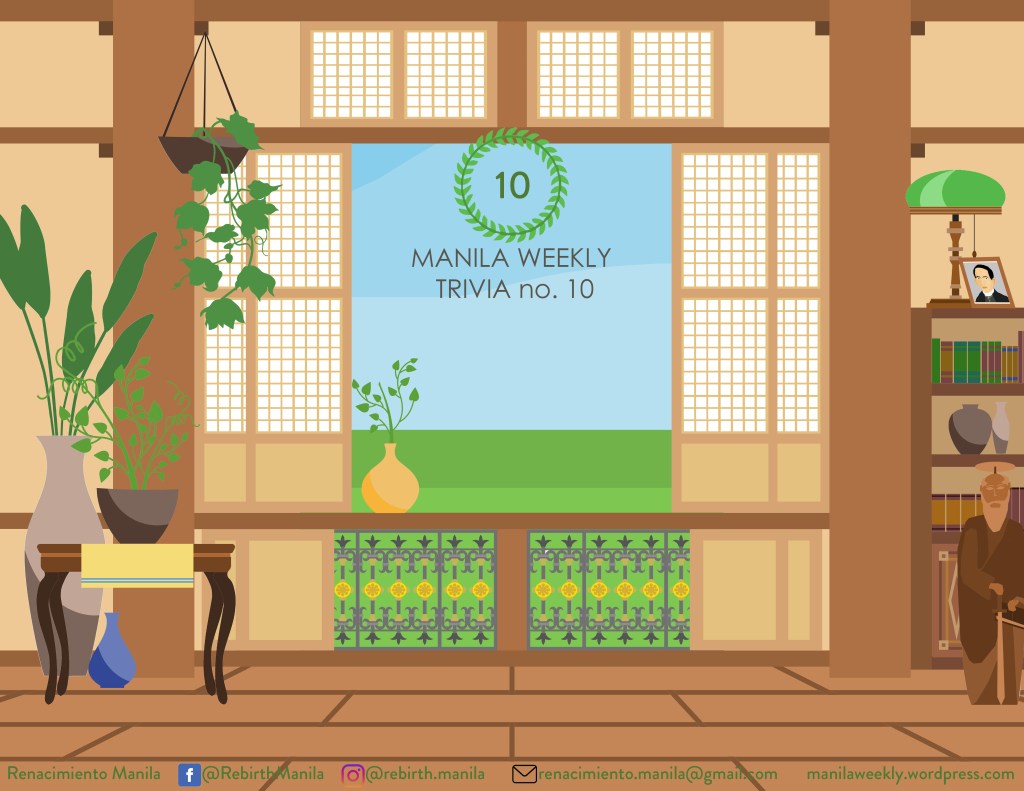

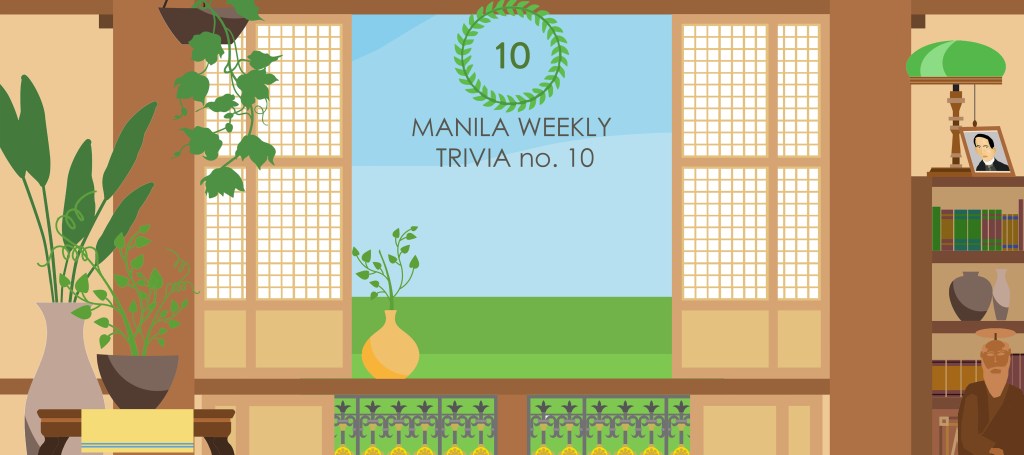

Examples of calado designs commonly found in the bahay-na-bato. Source: (Zialcita & Tinio, 1980); A door opening with a calado screen on top. Casa Manila, Intramuros.

Aside from facilitating the distribution of ventilation, the calado also served as the embellished fixture which greatly contributed to the character of the house. Calado was the translation of the essence of permeability in the bahay kubo, turned into a brand new fixture in a larger and more solid structure which allowed heat and air to move around instead of congesting at one part of the house. This traceried screen on top of partitions were an eclectic mix of Jugendstil (Art Nouveau), Art Deco, and even Revivalist styles of Classical, Gothic, and Mudejar. The Filipinos’ attachment to nature and ingenious creativity transformed these styles properly together with the abstraction of notable botany like the sampaguita, irises, roses and lilies. Therefore, aside from the structure’s openness to nature itself, it also donned nature through its ornamentations like a garden of freshness and simplicity on its walls and fixtures (Zialcita & Tinio, 1980).

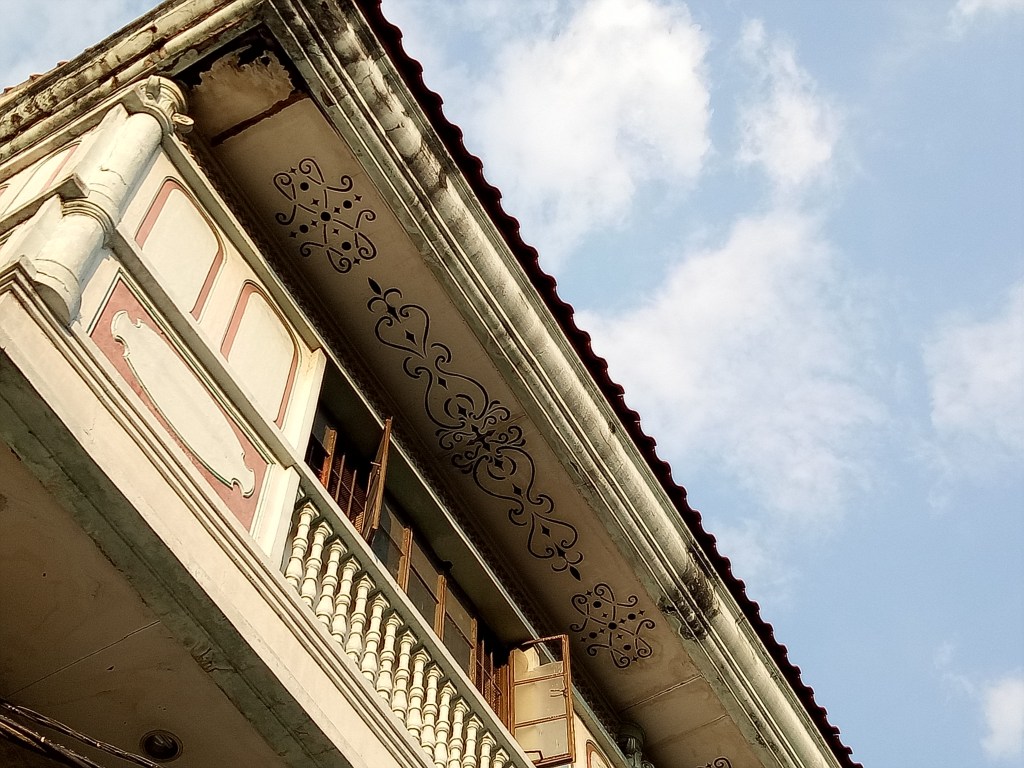

BONUS: Even the underside of eaves which serve as exit points for hot air have traceried patterns as ornamentation.

References

Buensalido, J. L. (2014). Random Responses: A Crusade to Contemporize Philippine Architecture. Makati: Buensalido + Architects.

Cultural Center of the Philippines. (1994). CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art. Manila: CCP.

Reyes, E. V. (2013). Philippine Style: Design and Architecture. Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Turalba, M. V. (2005). Philippine Heritage Architecture before 1521 to the 1970s. Anvil Publishing.

Zialcita, F. N., & Tinio, M. I. (1980). Ancestral Houses. GCF Books.

Texts and photographs by Bea Dolores

All rights reserved by the author.

21 June 2020

This article is an excerpt from the author’s undergraduate architectural thesis. Any form of plagiarism is prohibited. We encourage the use of paraphrasing, summarizing and/or revision, and to utilize the references provided above. For more information, contact the author through Renacimiento Manila’s social media platforms.

Leave a comment