Joshua Tulod and Diego Gabriel Torres

25 October 2020

Filipinos traditionally go to cemeteries during All Saint’s Day or ‘Undas’ to visit the graves of their departed loved ones. But this year, all cemeteries, columbariums, and memorial parks across the country are closed to the public because of the pandemic.

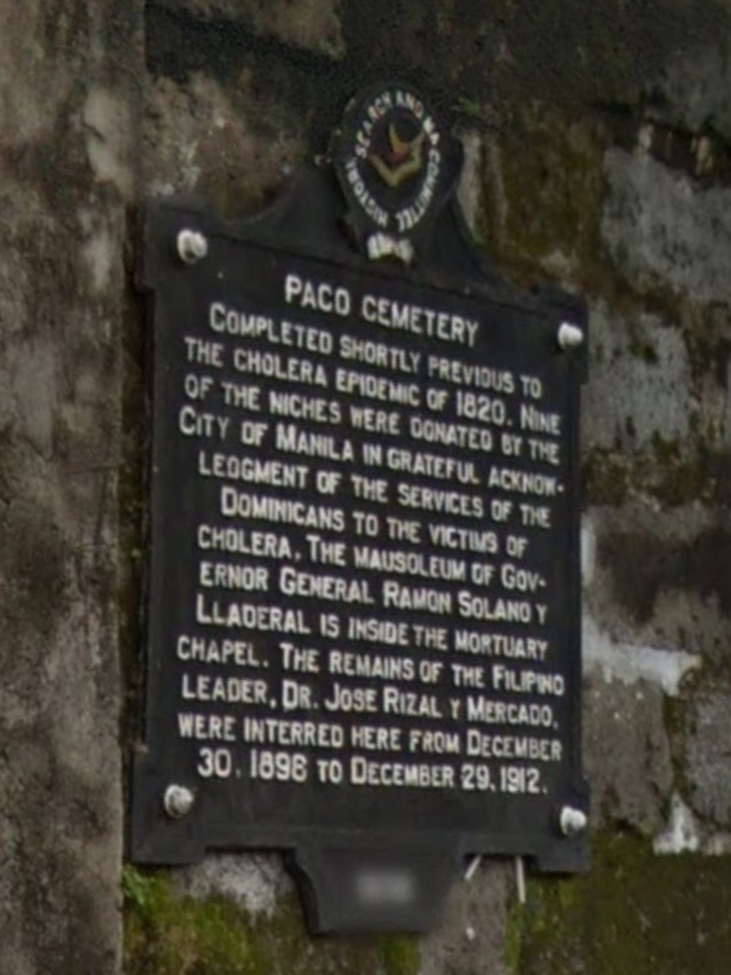

Epidemics have always been part of Manila’s history, even shaping the city’s development. Smallpox and cholera epidemics in the 19th century spurred the creation of many of Manila’s cemeteries. One such cemetery was the Cementerio General de Dilao, known today as Paco Park.

The Cementerio General de Dilao or Paco Cemetery was built due in part to the cholera outbreaks that swept the city in the 19th century. It was developed and planned by Maestro de Obras Don Nicolas Ruiz. The cemetery was officially opened in 1822, although burials were already allowed at the cemetery before it opened.

Paco Cemetery is circular in shape, with two enclosures. The inner enclosure was part of the original cemetery structure. The walls were built with five tiers of niches for burials, with a total of 1,782 niches (including those in the outer wall). A new outer wall was built in the middle of the 19th century to accommodate the growing needs of the city. Pathways for promenades were built later on top of the walls. A small, domed Roman Catholic chapel was also built inside the walls of the park and was dedicated to St. Pancratius.

Image credits: (Left) Public domain, (Center) Photo by Dennisraymondm, released under CC-BY-SA 3.0. Left and center pictures are retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. (Right) screenshot from Google Maps Street View.

The niches could never be permanently owned, and so after four or five years the relatives of the dead would have to renew their lease. Otherwise, the remains of the deceased would be taken out, to accommodate new burials, and thrown in the bone pit located at the Osario.

Behind the mortuary chapel is a gated space called the Osario or Angelorio. It was a place of interrment for infants and children. However, it is also used as an ossuary (hence the name) where bones are collected and stored if the niche rental was not renewed.

Several important figures in Philippine history were buried in Paco Cemetery. These include the former Spanish Governor-General Ramon Solano y Lladeral, General Lawton, and a number of bishops. Their bodies are mostly interred within the chapel.

Screenshots from Google Maps Street View.

The GomBurZa priests – Fr. Jose A. Burgos, Fr. Mariano C. Gomes and Fr. Jacinto R. Zamora – were buried in Paco Park after their execution by garrote because of charges of subversion arising from the 1872 Cavite mutiny.

Our National hero Dr. Jose Rizal was also buried originally in Paco Cemetery after his execution at Bagumbayan in 1896. His remains were exhumed in 1898, but a cross (with his reversed initials “RPJ”) still marks his gravesite within the park.

The Cemetery became an icon of Manila, and was frequented by tourists and visitors during the Spanish and American period. Paco Cemetery, along with many of Manila’s Spanish era cemeteries, was closed in 1913 as part of the campaign to improve Manila’s sanitation.

Paco Park also has two markers – facing the chapel, on the left is titled Mute Witnesses to the Burial of the National Hero Jose Rizal, dedicated to the old acacia trees that were ‘witnesses’ to where Rizal’s body was initially interred. On the right is a marker, a tribute to the National Artist Ildefonso Paez Santos, the first landscape architect in the Philippines.

Paco Cemetery was declared a national park in 1966 and has since been restored as a public park. It is administered today by the National Parks Development Committee.

Today, Paco Park is famous as a venue for prenup shoots and garden weddings. The peaceful atmosphere makes the park an ideal location for dating couples, tour groups and families looking for a quiet spot in the city. Paco Park also hosted cultural events such as ‘Paco Park Presents’, where musicians and chorales performed traditional Filipino music.

Paco Park at regular school days used to be quite filled with groups of students practising for speech choirs and other school requirements, usually by sections, despite the fact that crossing the streets surrounding the park is tricky, thanks to the truck lane. Paco Park also was site to class pictures of some of the earlier Manila Science High School batches.

But for now, Paco Park – just like its successor cemeteries in Manila – remains closed to visitors as a result of the pandemic.

References

Gaerlan, M. R. (2014). Sampaloc’s Sacred Ground. Quezon City: Gaerlan Management Consulting.

https:// bluprint. onemega. com/escuela-taller-paco-park/

http:// historicalpaco .blogspot .com/2015/08/paco-park-cemetery.html

angolanews. org .uk/paco-park⅝-and-cemetery-manila-the-whole-lot-youll-want-to-know/

In V. Almario (Ed.) Sementeryong Paco. (2015). Sagisag Kultura (Vol 1). Manila: National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

Blukaraboo (2020). Exploring Paco Park and Cemetery Manila.

Manila Science High School Alumni Foundation, Inc. (2013). Ginto’t Dalisay: The First 50 Years of MaSci. ISBN No. 978-971-95749-1-0

Other Historical Markers and signs

Text co-written by Joshua Tulod and Diego Gabriel Torres. Renacimiento Manila. All rights reserved.

The Renacimiento Movement. What, then, is the Renacimiento Movement? The movement is the core philosophy of the organization. It is founded on the reality that heritage is a cornerstone of holistic development and that it is indispensable in ensuring quality of life. As such, cultural revival is necessary for the promotion of heritage in the national agenda. Heritage should be driven by the people, regardless of race, gender, creed, or religion. This cultural revival can be achieved through the following ways: government support, the advancement of private initiatives, and the engagement of the people.

Leave a comment