Arch. Carlos Cucueco III & Diego Torres

Art by Diego Torres

08 Nov 2020

CAMPO SANTO: MANILA’S CEMETERIES, PAST AND PRESENT

In every settlement, there is a place for the living as well as for the dead. Such cities for the dead are sometimes referred to as a Necropolis. Manila is not an exception.

The city of Manila has a massive necropolis to the north of the city, formed by three cemeteries whose historical value are just as important as their role of being final resting places of the dead. Today, we will discuss Manila’s storied cemeteries, past and present, to get a glimpse of the story of the development of the city’s places for the dead.

MANILA’S NECROPOLIS

La Loma Cemetery

This cemetery was founded in 1884 by a Franciscan priest named Fr. Ramon Caviedas. The cemetery is located in the northern part of the district of Sta. Cruz, although its old name was Cementerio de Binondo. Due to its location in the hilly terrain of La Loma, the cemetery later came to be known as the Cementerio General de La Loma. During the Spanish Era, this cemetery was an ideal place for burial because it was a consecrated place, and thus it became the final resting place of numerous prominent personalities. Interestingly, this privilege was used as a blackmail by Spanish authorities for the people not to participate in the Philippine Revolution. The cemetery was the site of fierce fighting between US Forces and Republican Armies during the Battle of Manila in 1899, which opened the Philippine-American War. During the Japanese occupation, the cemetery became notoriously known as a site for executions.

During its early years, the grounds of the cemetery was demarcated by a stone fence with a height of three meters. The main entrance was an impressive portal, adorned with intricate wrought iron gates, and stone sculptures. Unfortunately, only the stone pillars of the gate remain. Although the beautiful gate was lost, one modern entrance facing Rizal Avenue is adorned with a modern gate similar to the old gate in some of its details.

The cemetery has a funerary stone chapel dedicated to St. Pancratius which is still standing today. The exterior of the chapel features a beautiful dome, stone buttresses, intricate stone carvings and delicate wrought iron grills. The interior of the chapel features only a simple yet elegant design with the use of black and white stone tiles, elegant columns, and a simple altar with the crucified Christ as the focus. Unfortunately, due to its old age, funerary services are no longer held in the old church, and a new church was built near the entrance of the cemetery. Aside from the chapel, various mausoleums, tombs, and other types of burial places in different architectural styles can be found inside the cemetery, including the old Spanish period niche burials.

Manila Chinese Cemetery

In the late 19th century, another cemetery was established by Lim Ong and Tan Quien Sien (known also as Don Carlos Palanca) to cater burials for the non-Christian Chinese. This was because ecclesiastical authorities prohibited the burial of non-Christians on consecrated places such as La Loma Cemetery.

Structures inside the cemetery often vary depending on the social status of the person buried. For poorer people, this meant smaller plots and narrower access to these plots. On the other hand, some sections of the cemetery such as the Millionaires’ Subdivision and Little Beverly Hills were allotted for the rich. The mausoleums in these areas are often confused with little houses because these include amenities that can be found in a functional modern house such as air conditioning systems, working plumbing fixtures, kitchen area and electrical appliances. In terms of aesthetics, different architectural styles exist just like in other cemeteries.

Aside from the mausoleums, the cemetery also contained numerous Chinese temples. One of these temples is the Chong Hock Tong, a temple established in the 1850’s – years before the creation of the Cementerio de Binondo. Unfortunately, the original wooden structure was demolished due to termite damage. The structure was then hastily rebuilt using stone materials and was unveiled in 2017.

Manila North Cemetery

Formerly part of the La Loma Cemetery, the Cementerio del Norte was opened as a final resting place for anyone regardless of their religious belief. It is interesting to note that one of Rizal’s final wishes was to be buried in a place called Paang Bundok, which is the area where Manila North Cemetery is located today.

Because this cemetery is the largest in Manila, various types of burial structures and funerary monuments in different sizes, colors and styles can be found here. Also, many prominent figures in different fields are buried in this cemetery. However, the capacity of the cemetery affected the overall maintenance of the cemetery. Thus, the landscape of the cemetery changed from a final resting place with vast greeneries – which was in style during the late 19th cand early 20th centuries – into a place where you can only see overflowing funerary structures. Another problem that the cemetery faces is the growing numbers of informal settlers. Informal settlers have occupied some mausoleums which they have turned into their homes in return for being caretakers of the graves that they occupy.

Manila South Cemetery

Interestingly, even though the location of this cemetery was located within the vicinity of Makati City, the Manila South Cemetery is managed by the Manila City Government. This was because in 1925, the Manila City Government acquired the lot for the Manila South Cemetery from a part of the Hacienda San Pedro de Macati owned by the Ayala-Zobel clan. Although not as architecturally diverse as the other cemeteries of Manila, it is notable because of prominent figures who are buried here.

MANILA’S LOST CEMETERIES

Aside from these famous and still functional cemeteries, Manila has had in its long history, cemeteries which thorugh time were abandoned, closed, and built over. Some entries here are common knowledge, while others may come as a surprise.

Plaza Santo Tomas and Mehan Gardens

During much of the Spanish period, most burials were done inside the churches or in a nearby churchyard. Famous amongst these would be San Agustin Church’s still functional crypt in the old monastery that houses the Augustinian museum today.

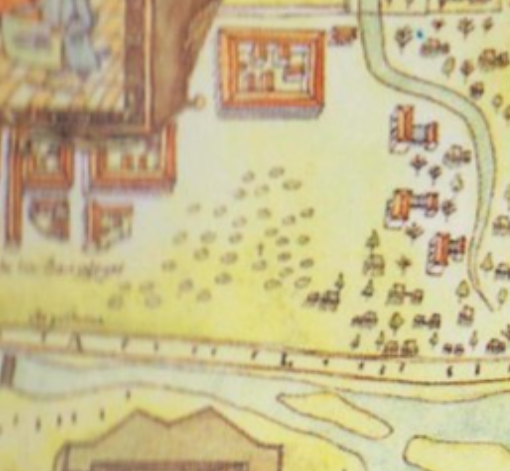

But just a few blocks from San Agustin, and just 100 feet from the Manila Cathedral, one will find a plaza that was once a cemetery. Plaza Santo Tomas begun as a vacant lot which was purchased in 1627 by the Dominican Order (whose famous church and convent – Santo Domingo – was just east of the lot) to be used as a cemetery for the order. The lot, which was flanked by Dominican run institutions such as Santa Rosa College and UST was also used as a garden with a fence around it, as seen in a map of Manila by Antonio Rojas dated 1713. The garden and cemetery was purchased by the government in 1861 and was supposed to be the location of the statue of Queen Isabel II (now in Puerta Isabel II). Due to political upheavals, the monument was moved elsewhere and later a monument to Archbishop Benavides, founder if UST, was erected in the spot.

Also shown in the 1713 Rojas map is a cemetery just east of Intramuros, outside the walls. It is labelled as “Sepultures de Sangleyes” or Chinese graves. There is even a grave cross in middle. The area is now part of Mehan Gardens.

Cementerio General de Paco (Paco Park)

The most famous cemetery of Manila is of course the former Cementerio General de Dilao or Paco Cemetery. This has been discussed in detail in a previous article.

But in summary, the Paco Cemetery was opened in 1822, with burials starting as early as 1820. The cemetery for Manila’s elite was soon filled with the dead as a result of the cholera epidemics that tormented the city. The peculiar design of the cemetery, and the practice of pulling out corpses who failed to pay rent, made it a major tourist spot in the 1800’s and early 20th century. New health policies eventually closed this cemetery in 1913.

The abandoned cemetery was turned into a park in 1961, and is now administered by the National Parks Development Committee (NPDC).

Balic-Balic Cemetery (Most Holy Trinity Parish Church)

One of the largest cemeteries of Manila used to be located on the hills northeast of the town of Sampaloc, an area known as Balic-Balic. The changing policies regarding burials meant that the dad needed to be situated in proper cemeteries. The cholera epidemic also strained Manilas inadequate burial grounds. In 1884 a large cemetery was completed in the hills of Balic-Balic. The rectangular lot had a funerary chapel in the far end and had walls with burial niches similar to Paco Cemetery. Its main entrance was a grand wrought iron gate similar to that of the old La Loma Cemetery, which was flanked by stone and wrought iron fences.

The cemetery was closed in 1913, along with other Spanish era cemeteries. In 1927, the old funerary chapel was reused as a parish for the growing community. That chapel today is the Church of the Most Holy Trinity.

Santa Cruz Cemetery (Espiritu Santo Parish Church)

Another cemetery from the late Spanish period is the old Santa Cruz Cemetery. The 863 sq.m cemetery was built near San Lazaro Hospital along Calazada de San Lazaro (Avenida Rizal today), at the edge of the city. The cemetery only had wall niches for burials, and did not accommodate ground burials.

The cemetery was closed in 1913 and like Sampaloc’s Balic Balic cemetery, the cemetery was later reused as a parish church. The former Santa Cruz cemetery is now the location of the Espiritu Santo Parish Church.

Two Malate Cemeteries (Remedios Circle and Harrison Plaza)

Malate Cemetery was located east of Malate Church, of some distance from behind the church compound. The circular cemetery was devastated during the fierce fighting in Malate during the Battle of Manila in 1945. The property was later sold by the church to the government. Remedios Circle occupies the site of the old Malate Cemetery.

South of Malate lies another, much larger cemetery. Known as the Maytubig American and Native Cemetery, the cemetery was situated east of the old Fort San Antonio Abad, near the marshes that formed the boundary of Manila and Pasay at the time. The cemetery was established in the 18th century as the Polvorista cemetery to accommodate those who died during a smallpox epidemic. The cemetery was later used by the Americans for burial of casualties of the Spanish American War and the Philippine-American War. The site is labelled as “Native Cemetery” in a map from 1907.

The site of the cemetery is occupied today by Harrison Plaza – which is currently being demolished to make way for another SMDC property.

Old Cemeteries of Tondo (near Pritil Market and former Tutuban Railway Yard)

Tondo was one of Manila’s biggest communities even during the 19th century. The Old Cemetery of Tondo was located in Barrio Tutuban. The cemetery became infamous because of the foul odors emanating from the decaying corpses as a result of frequent flooding and due to groundwater being near the surface.

The 1882 cholera outbreak necessitated a new cemetery for Tondo. Land was appropriated in Tondo’s Barrio Lecheros for a new cemetery. At the height of the epidemic, more than 2000 corpses were buried in the cemetery, leading to its closure. Public demand forced it to reopen in 1884. The second cemetery used to stand near Pritil Bridge at Barrio Lecheros surrounded by water. Although it was on a patch of land one meter higher than the surrounding area, ground water eventually penetrated the burials and so in 1902, the Americans closed the cemetery as a danger to public health.

The Old Tondo Cemetery at Tutuban was permanently closed in the 1882 and was soon runover by the tracks and trainyard of the Manila-Dagupan Railway, now PNR. The site is now built over by Robinsons Tutuban, in the portion close to Dagupan St. and Calle Moriones.

The second cemetery is shown in a map of Manila from 1907 and 1915. The site of the cemetery is flanked by the following streets: Calle Sande (Nicolas Zamora St. today), Calle Herbosa (just a little bit) and Calle Francisco. Calle Franco and Calle Gerona bisect the property today. The former cemetery is now occupied by houses and shops, just south of Pritil Market.

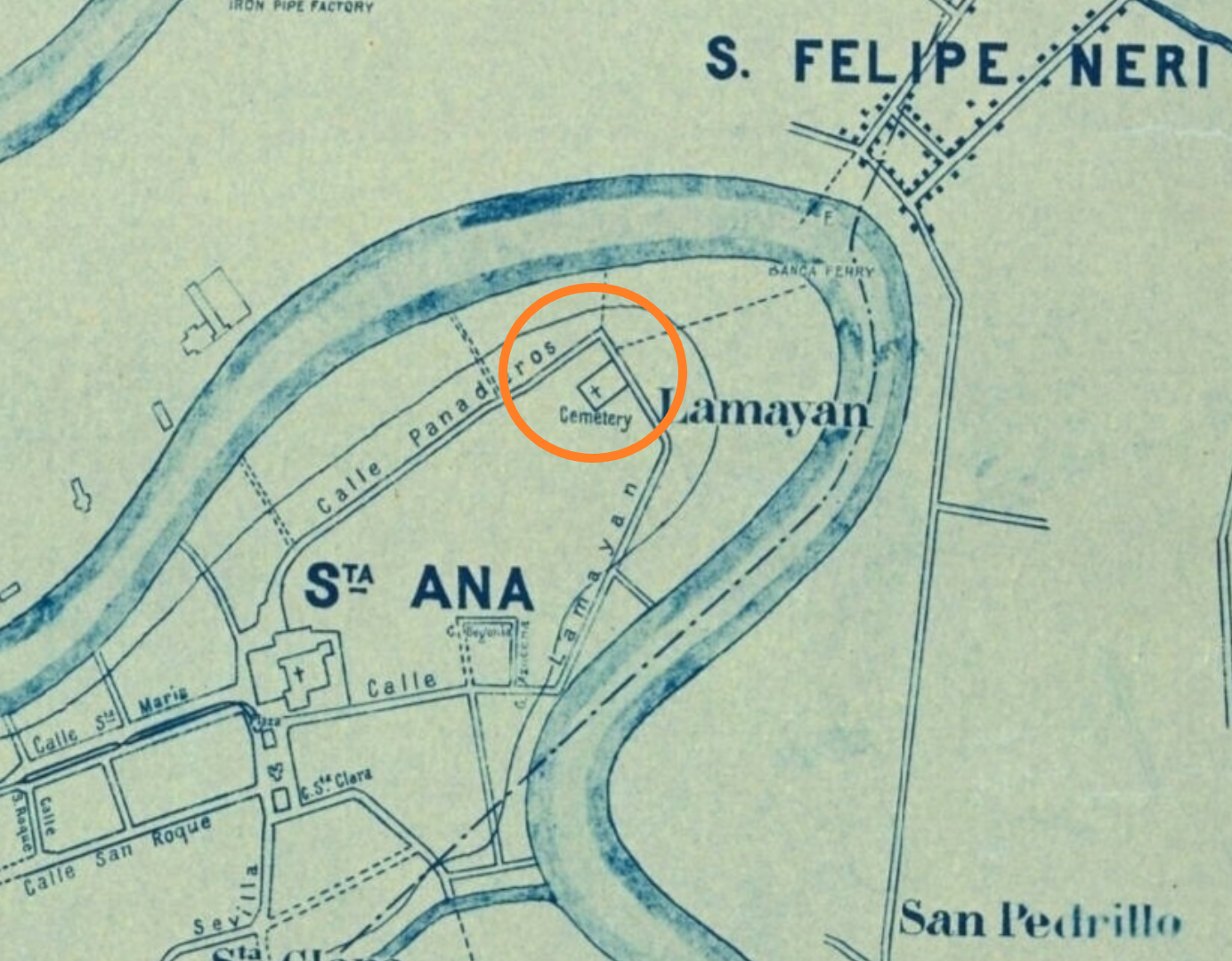

Santa Ana Cemetery (along Calle Lamayan)

The former cemetery of Santa Ana was closed along with other Spanish era cemeteries in 1913. The cemetery used to be located along Calle Lamayan, and its location is now occupied by a portion of Trinity Woman and Child Hospital and Santa Ana Town Homes 2.

Pandacan Cemetery (Pandacan Oil Depot Complex)

Another cemetery shown in the 1907 map of Manila was the Pandacan Cemetery. The cemetery was located just outside of the town, and was accessible through the street called Calle Cementerio or Calle Jesus. The area is now part of the property that used to be the location of the vast Pandacan Oil Depot complex.

References

Gaerlan, M. R. (2014). Sampaloc’s Sacred Ground. Quezon City: Gaerlan Management Consulting.

Torres, J. V. (2005). Ciudad Murada A Walk Through Historic Intramuros. Manila: Vibal Publishing House, Inc. , Intramuros Administration.

nhcp. gov .ph/cemeteries -of-memories -where -journey-to- eternity-begins

onenews . ph/cemetery-as -heritage-reliving -history-through- the-dead

La Loma Cemetery

beauty ofthe philip pines .com/la- loma-cemetery

life isa celebration . blog/2012/11/29/ the-old-and-dead -rich-of-la-loma

curator museo. wordpress. com/2007/07 /07/cementerio -de-binondo -la-loma-cemetery

lakwatsero . com/spots /campo-santo- de-la-loma-and-its -lumang-simbahan/#stha sh. K9txQtfv . dpbs

Manila Chinese Cemetery

fabulous philippines .com/chinese -cemetery-ma nila . html

amusing planet .com/20 16/04/the- luxurious-mausoleum s-of-manila. html

lifestyle .inquirer .net/242587/ must-try-undas-tour- visiting-the-manila- chinese-cemetery

news. abs-cbn .com/ancx/ culture/spotlight/11/01/20 /at-the-chinese-cemetery -art-deco -structures- are-the-fin al-resting -place-of-manilas -old-taipans

Manila North Cemetery

the urban roamer. com/ roaming -the-manila -north-cemetery

lifestyle .inquirer .net /248795 /rizal-not- get-dying -wish-simple-burial -paang-bundok

Manila South Cemetery

the urban roamer. com/ manila- south- cemetery

curatormuseo.wordpress . com/2019/11 /01/balic-balic- cemetery-burials-disinterment-1910-1919/

rappler .com /newsbreak/iq/ cemetery-trivia-former-burial-grounds

nhcp . gov . ph/cemeteries -of-memories- where-journey-to-eternity-begins

onenews . ph /cemetery-as -heritage-reliving-history- through-the-dead

Text co-written by Arch. Carlos Cucueco III & Diego Torres. Renacimiento Manila. All rights reserved.

The Renacimiento Movement. What, then, is the Renacimiento Movement? The movement is the core philosophy of the organization. It is founded on the reality that heritage is a cornerstone of holistic development and that it is indispensable in ensuring quality of life. As such, cultural revival is necessary for the promotion of heritage in the national agenda. Heritage should be driven by the people, regardless of race, gender, creed, or religion. This cultural revival can be achieved through the following ways: government support, the advancement of private initiatives, and the engagement of the people.

Leave a comment