RailwaysPh

15 November 2020

It is by the railway that brings commuters closer to their destinations more efficiently compared to other means, in terms of capacity and comfort. For the colonizers that saw with the potential of transporting resources around the country, they had harnessed the technology of steel and steam to further aspects that, in turn, will further their power.

The Philippines—or at least a handful of regions—has been witness to the heavy rail iron horses of the Ferrocarril de Manila-Dagupan that galloped the tracks from the capital from to the province, a few years before the 19th century came to close. But before the larger engines wailed with their silbato or horns, there were the trams or the Manila Streetcar system.

Preceding documents

In 1875 a royal decree was issued under King Alfonso XII’s rule to address issues on transportation, particularly the need for railroads in the Philippines.

The following year, the Administracion de Obras Públicas (Department of Public Works) submitted the Formularios para la reducción de los anteproyectos de ferrocarriles (lit. forms for the reduction of railway blueprints) which details forms for technical requirements that future railway constructions must adhere to. Also in 1876 came the Memoria Sobre el Plan General de Ferrocarriles en la Isla de Luzón (General Plan for Railways), which was submitted by Engineer Eduardo López Navarro that details plans for railways in Luzon, notably the Philippine National Railways—then Ferrocarril de Manila a Dagupan.

Tranvía de Manila (Spanish colonial period; 1882–1900)

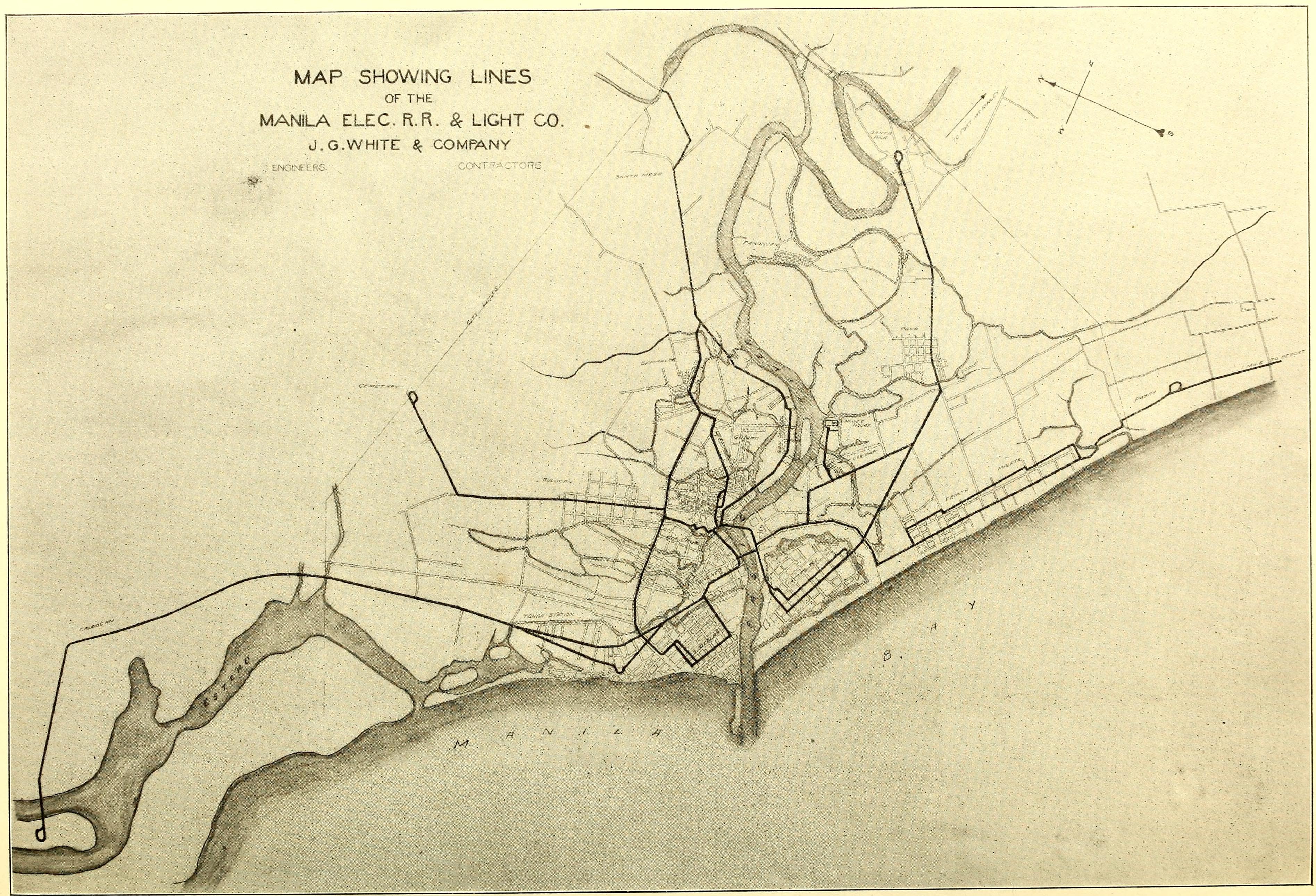

Plans for a five-line tramway system originated from León Monssour’s proposal in Madrid in 1878. These include drawn lines radiating from Intramuros, a line to Malate Church, a line serving Sampaloc locals that passes near San Sebastian church, another through Azcarraga (now C.M. Recto) in Tondo, and a line to Malacañang Palace. However, the plan would only be realized by an entrepreneurial initiative. The concession for construction of the tramway was awarded in 1881 by the Spanish government.

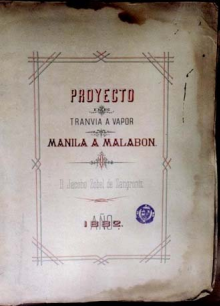

The following year, in 1882, La Compañía de los Tranvías de Filipinas was a business venture by Jacobo Zóbel y Zangroniz, engineer Luciano M. Bremon, and banker Adolfo Bayo.

Having estimated that a line to Malacañang would not reach expected demands, it was also in 1882 when the Compañía requested for a change of plans by having a route pass through Binondo Bridge instead. The construction of the Malabón Line is a deviation from the original plans by Monssour; nonetheless, the Malabón line proved to be a commercial success.

The Malabón Line’s length starts from the Plaza del Águila, in Tondo, and all the way to the San Bartolomé Church in Malabón, specifically the church square; sometimes referred to as Dulo. The tram stations can be located at Galanga and Caloocan, and travels at the left side of the existing roads.Between the Tondo and Caloocan stations, the tram line ran parallel to that of the Manila-Dagupan Railway, with a stop connecting the separate railroads. Stations of this particular line can be found at Pritil and Maypajo as well.

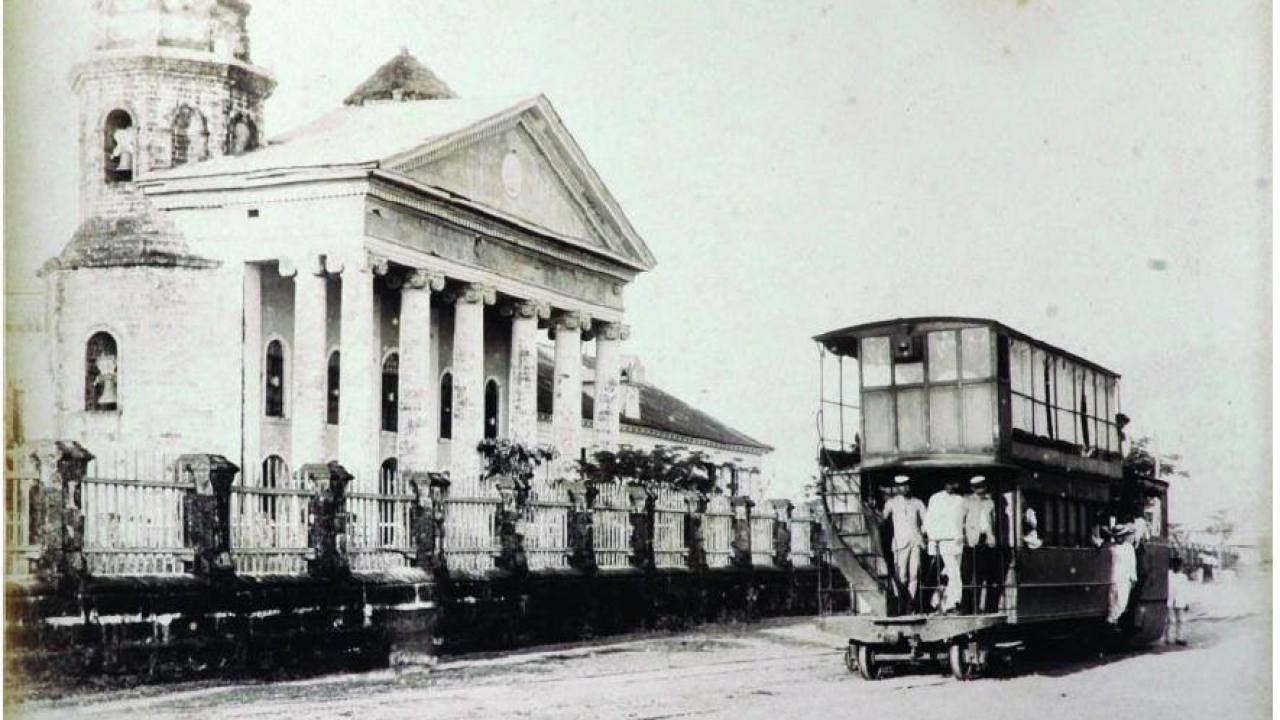

The Malabon Line was very profitable during the Spanish colonial era. It was bustling with transporting goods from agricultural businesses (such as cigars, milkfish, and sugar) from the eponymous city and Navotas. The coaches that traveled to Malabon and back at Manila are double deckers, pulled by German-manufactured locomotive “steam dummies”. The upper deck is reserved for the primera clase (first class), and the street-level accommodation is for the segunda clase (second class).

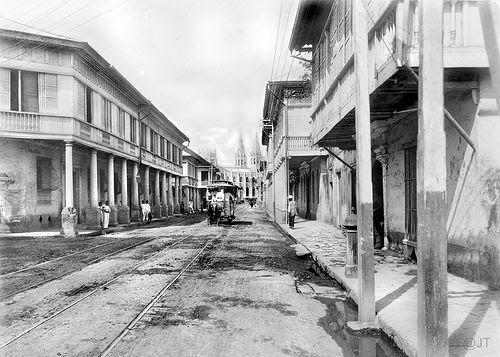

Most of the construction work for the tramway took place between 1883 to 1886. Among the five lines, the Tondo Line was first accomplished, having been inaugurated on December 9, 1883. The Intramuros Line came second, which operated in 1886; followed by the Sampaloc Line that served the arrabales near San Sebastian Church (now colloquially known as Legarda) in 1887. The following year saw the completion of the first steam railway, Malabón Line, whose construction was prioritized from that of the Malate Line which opened in 1889.

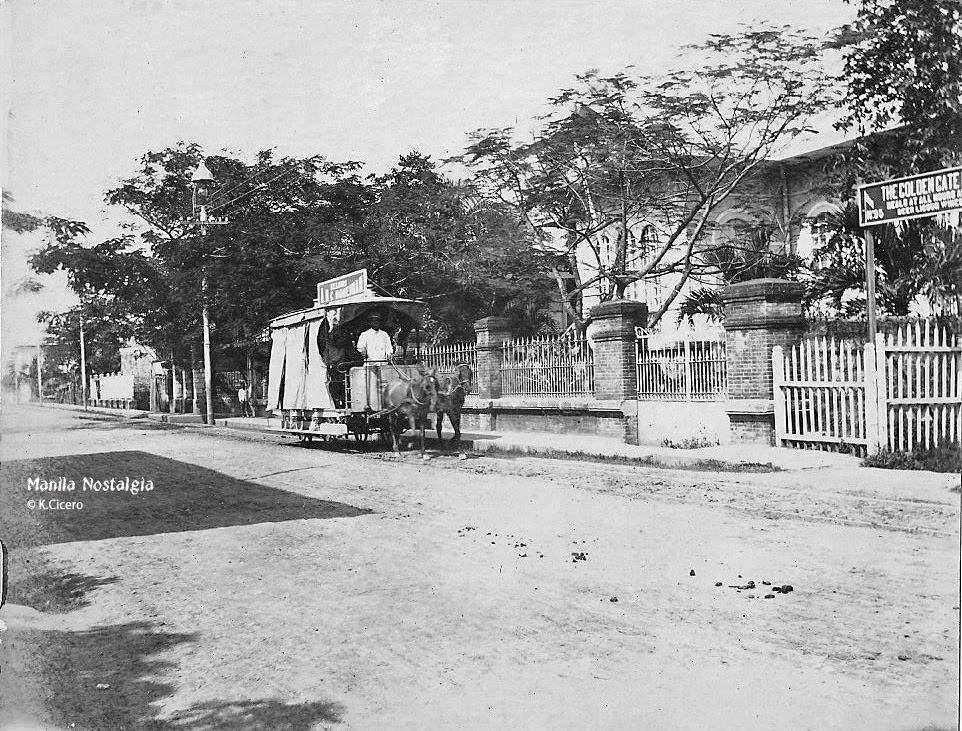

Unlike the Malabón Line, the lines Intramuros, Malate, Sampaloc, and Tondo utilized horse-drawn coaches. The seating capacity of each tranvía de sangre (horse-pulled tram) is 12, and can accommodate 8 more standing passengers. A central station just outside Intramuros was also built.

In 1889, additional carriages were added to the existing light rail fleet. The tram company also offered three classes; the primera clase costs 20 cents, the segunda for 10, and the tercera for 5 cents. As for the Malabón Line, it operated four steam locomotives, hauling two coaches each on the revenue. Overall, the length of the tram lines was 16.3 kilometers long.

In line with the events of the Philippine Insurrection, the Spanish withdrew their governance in 1898, thus ceasing the expansions of the tranvía network by the Compañía. In 1900 the Intramuros Line suspended operations. This makes it the shortest-lived railway line in Philippine history.

Manila Electric, Railroad, and Light Company (American colonial period; 1902–1945)

At the time of the Philippine-American War, the Malabon Line was dubbed the Kansas and Utah Short Line. This particular line was controlled by an army of Americans that time.

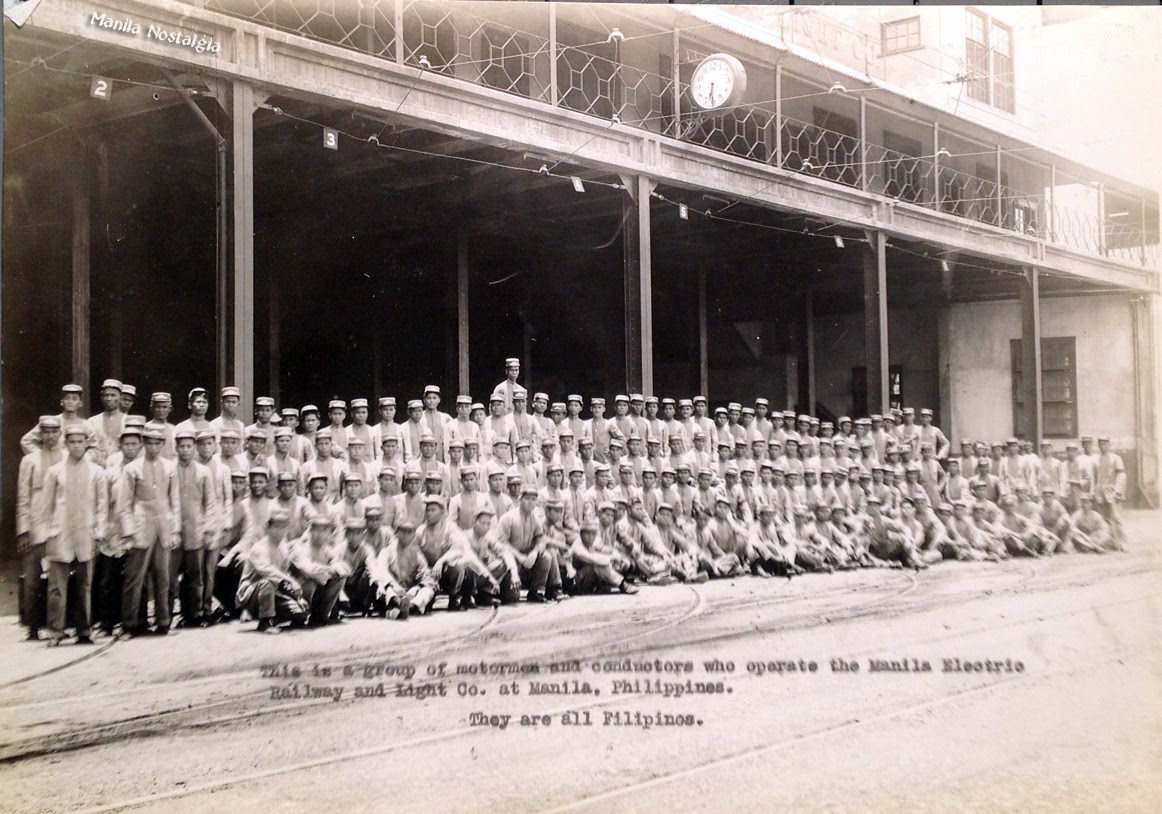

The tramway was in a derelict condition as the Americans had begun their control throughout the archipelago. In 1902, Act No. 484—the bill for the bidding of the streetcar system—was passed by a group of five American and three Filipino legislators.

When the Philippine Commission conducted a census in the same year, the technical aspects of the railway were recorded. The tracks used on the system weigh around 16 kilograms (35.3 lb), and the ballast work utilized sand or a mixture of sand and sharp ballast. Interestingly, the tranvía was built with the same gauge as that of the Manila-Dagupan; that is, 1067 millimeters (3 ft 6 in).

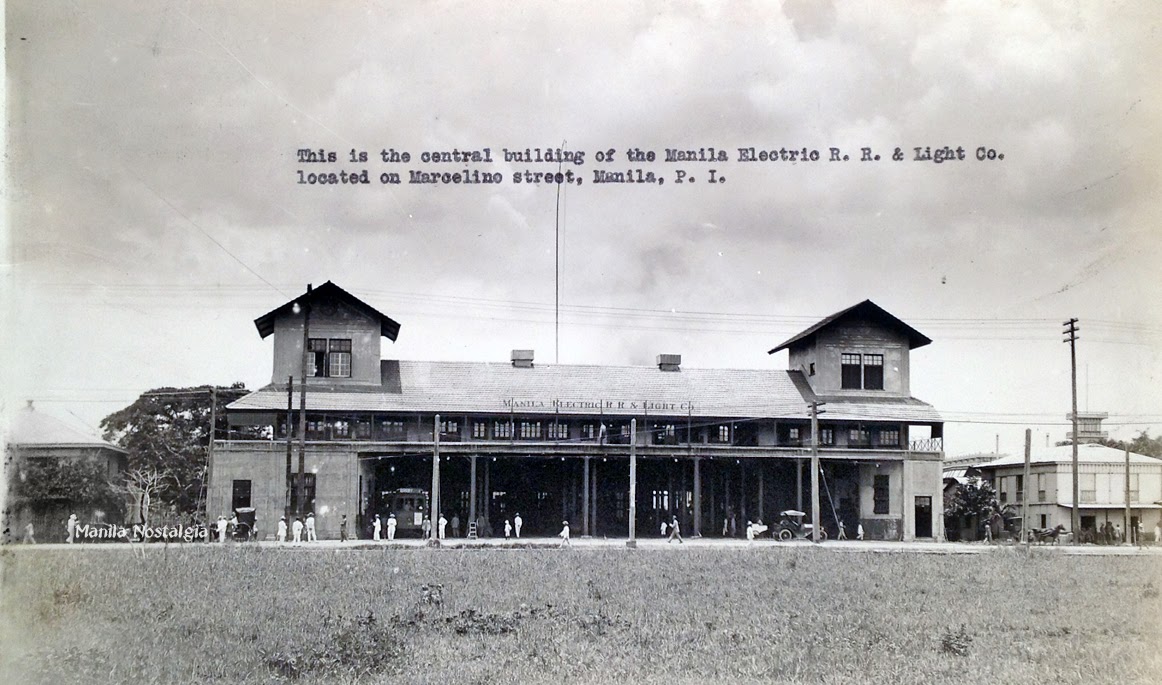

On 24 March 1903, Charles M. Swift, an American businessman, won the franchise for the Manila Electric Company. J.J. White, was then commissioned for the construction and engineering purposes. The following year, in 1904, the light rail transit company Compañía de los Tranvías de Filipinas and the Spanish electricity provider company La Electricista were both acquired by the Manila Electric Company, and subsequently in 1905 the tramway—better known as streetcar in North American terminology—was inaugurated.

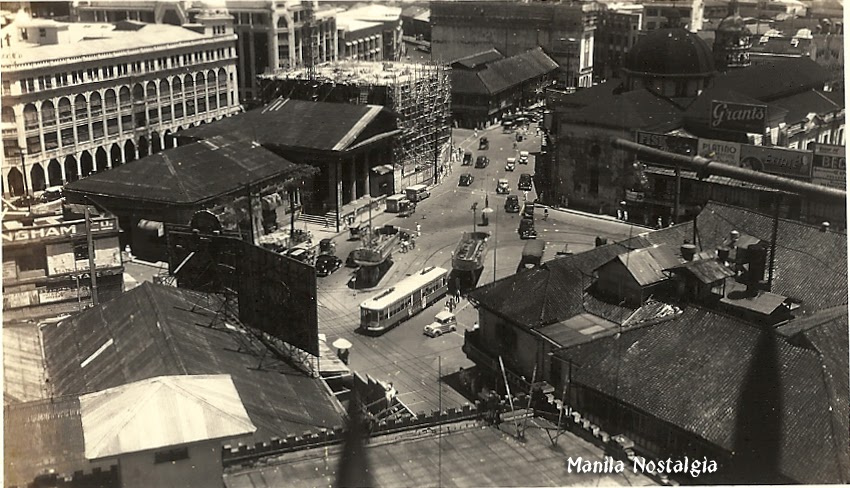

As the year concluded, the modernization projects achieved a total of 60 kilometers (40 mi) of light rail track. A major contributor to the overall trackage was the construction of the Pasig Line, which added 11.6 kilometers (7.2 mi). Additionally, the Spanish era horse-drawn trams were replaced with the electric-powered coaches of double wheel trucks and closed sides. (To note, the Spanish era trams had open sides and wheels decorated with a floral pattern of steel.)

The Manila Suburban Railway was another franchise by Swift in 1913. The company operated the streetcar line that runs south to Fort Mckinley from Paco. It did not take long before Swift merged the franchises of Manila Electric Company and Manila Suburban Railway to become the Manila Electric, Railroad, and Light Company, or Meralco.

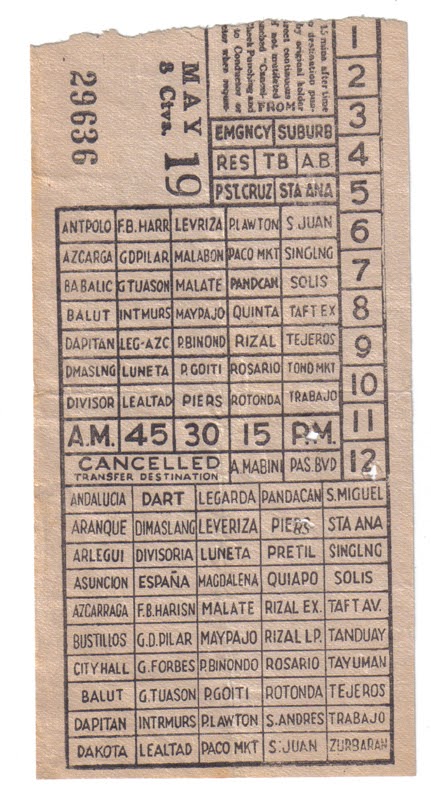

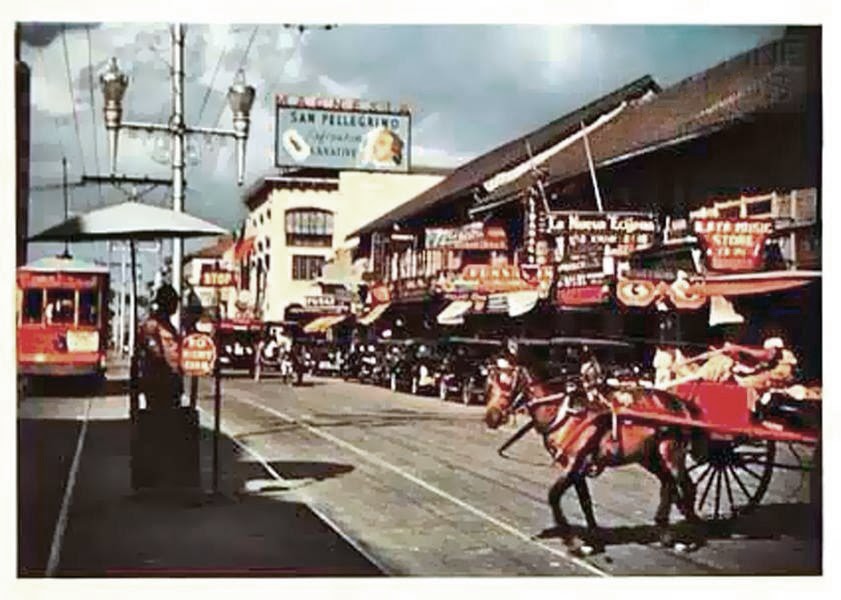

The streetcar services Meralco offered in a span of nearly four decades were expanded from the lines built during the Spanish era, connecting Binondo, Escolta, San Nicolas, Tondo, Caloocan, Malabon, Quiapo, Sampaloc, Santa Mesa, San Miguel, and going as far as Fort Mckinley in Taguig and Marikina. Most of the expansion efforts took place in the 1920’s for five years; by 1924 the streetcar fleet was a total of 170 coaches, produced in Meralco’s workshops.

The 1930’s was the peak of streetcar services under Meralco. It was regarded as a “state of the art” transport system. But aside from trams on rails, Meralco had also tinkered with “trackless trolleybuses”, or buses whose power sources are the same with that of the streetcars: catenary overhead wires, albeit without the rails. This experiment took place on Santa Mesa street, between the Rotonda and San Juan Bridge, and subsequently replaced the streetcar service there.

Towards the last years of the Manila streetcar system—at the onset of World War II—Meralco has expanded its road-based transportation services (i.e. buses), and in 1941 the streetcar fleet was reduced to 109. It was during the 40’s when Meralco’s source of income shifted into providing electricity. After the war, the company decided to abandon its transportation venture, thinking that reviving the streetcar system would be costly. And thus, the tranvia no longer strolled freely through the thoroughfares of Manila.

Trams in Corregidor (American colonial period and Japanese Occupation; 1901–1945)

Among the areas that the United States had converted into military bases, Corregidor is a special case. It has its own tram—or trolley system that served both the military and the residents of the tadpole-shaped island. It was also witness to the imperial motives of the Japanese, at least within the island. The trolley railway was built as such to assist the military workers in transporting goods that are shipped from the mainland United States, aside from constructing the fortifications within the area. During that time, steam engines were regarded as prime movers.

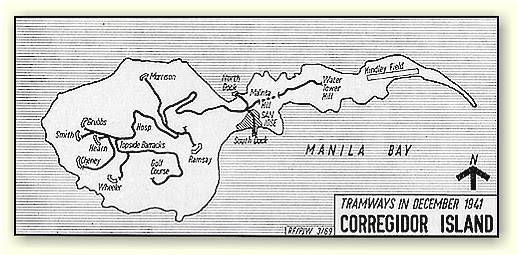

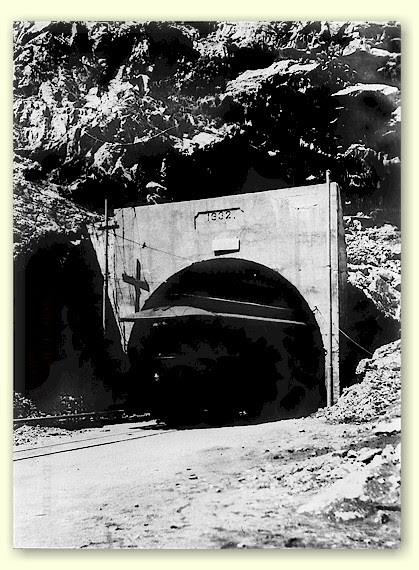

“The electric line started at the North Mine Wharf and connected junctions to Lorcha Dock and a junction to the South Mine Wharf . A junction was also built to connect Engineers Wharf From here a line ran to Barrio San Jose. Later, when Malinta tunnel was built, a line passed through it. The first station was at halfway to Middleside, serving the Corregidor Intermediate School , barracks and the stockade. From here a series of station were built that led to the end of the trolley line, just in front of the Mile Long Barracks at Topside. A car barn was located in front of the Ordnance Machine Shop, close to Topside.” Caption quoted from The Corregidor Railway System of the Corregidor Historic Society.

The tramway in Corregidor was at first a steam railway, similar to the Malabon Line. Steam tank engines of 0-4-0 were used to cope with the tight curves to travel on the rugged terrain of the island. The earliest rails laid out throughout the island connected major structures and the batteries for defenses.

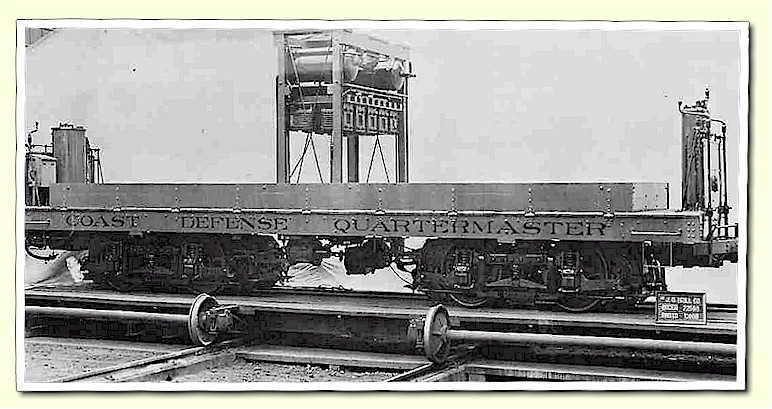

However, the island railway utilizes a narrower gauge, which measures 914 mm (3 ft), as this was the common practice for railways serving agricultural and construction purposes. While Meralco provided assistance in troubleshooting, it was the Quartermaster Corps who took charge of the railway. The soldiers who stayed on the island also served as the railroad’s workers.

Construction of the electrified lines was approved in 1907 by the US Congress. This was similar to the the Manila streetcar system. The Corregidor railroad—or trolley system—was electrified using 600V of direct current electricity on overhead lines. The electrification began in 1909. Subsequently, when the Malinta Tunnel was built, tracks were placed through; overall, the total track length on Corregidor is around 5.64 kilometers (18500 ft).

On 8 December 1941, the railroad was utilized to move tons of supplies and the hospital to Malinta Tunnel, using electric freight motors within two weeks. Subsequently on the 29th, major bombing on the area began, where the railroad suffered major damages; some bombs were able to cut the railway and the war’s intensity exacerbated the neglect on the tracks. While limited operations continued to push through, these were stopped eventually.

During the arrival of the Japanese in the island, the Americans used the broken railroad tracks as reinforcement for concrete barriers. Meanwhile, the trolley cars and engines were ultimately scrapped during the war, especially in 1942 when the Japanese had captured the island.

The Japs attempted to restore the railway in vain, having fixed a portion from Bottomside to Morrison Hill. Thus, they salvaged the rails and sent those to Japan as scrap, with the prisoners-of-war as the workers tasked to do the heavy hauling. Though the Americans managed to reclaim the island in 1945, the railway system was already gone; though at present a few tracks and rail lines may be seen, and the rest may be covered due to erosion over time.

Postwar

Both the tranvía at Manila and the Corregidor trolley lines were witnesses to development under the colonial era; the former having served communities, and the latter for military purposes. While these railways may be heritage we can call as pride, these bygone tracks are also a reminder of past and ongoing colonialism that shaped how our elders lived and how we do so today.

In the future, being independent of imperial powers and proactive political will suppressing our freedom, we can rebuild similar lines for the betterment of our mass mobility.

References

Cubeiro, D. (2018) Conectando la ciudad al mar: cambios en Manila con la llegada del tranvía (1880-1898) (in Spanish, PDF). Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) – CSIC.

Regidor, J.R., Aloc, D. (2017) Railway Transport Planning and Implementation in Metropolitan Manila, 1879 to 2014 (PDF). Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol. 12.

Gardner, R. (2004) Railways, Waterways, Stone-ways. Discovering Philippines.

Zobel y Zangroniz, J. (1884) Memoria y estatutos (in Spanish). Filipinas Heritage Library.

Gonzalez, M. (1979). The De Manila a Dagupan (PDF). Asian Studies Journal, 17, 18-36. University of the Philippines Diliman.

Satre, G (1998) The Metro Manila LRT System—A Historical Perspective. Japan Railway & Transport Review 16.

Jose, Ricardo T. (August 25, 2018). “Planning Metro Manila’s Mass Transit System”. riles.upd.edu.ph. National Center for Transportation Studies, University of the Philippines Diliman

Gopal, L. (2015) Manila’s Public Transportation – a pictorial essay. Manila Nostalgia.

Meralco (n.d.) “100 Years of Meralco: Colonial Outpost”. meralco.com.ph. Meralco. October 11, 2004. Archived from the original on September 18, 2009.

Philippine Commission (1903) Census of the Philippine Islands. Volume IV. United States Bureau of the Census, 1905. Retrieved from Google Books.

Feredo, Tony (June 6, 2011). “The Corregidor Railway System”. corregidor.org. The Corregidor Historic Society. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019.

Campbell, Don (June 6, 2011). “The Corregidor Tramway”. corregidor.org. The Corregidor Historic Society. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020.

Secretary of Commerce and Police (1907). United States Congressional Serial Set. Philippine Commission.

Morton, Louis (1953). The Fall of the Philippines. CMH Pub. LCCN 53-63678.

Text co-written by RailwaysPh; Art by Diego Gabriel Torres. Renacimiento Manila. All rights reserved.

The Renacimiento Movement. What, then, is the Renacimiento Movement? The movement is the core philosophy of the organization. It is founded on the reality that heritage is a cornerstone of holistic development and that it is indispensable in ensuring quality of life. As such, cultural revival is necessary for the promotion of heritage in the national agenda. Heritage should be driven by the people, regardless of race, gender, creed, or religion. This cultural revival can be achieved through the following ways: government support, the advancement of private initiatives, and the engagement of the people.

Leave a comment