Diego Gabriel Torres

29 November 2020

November 30 is celebrated all over the country as the day of birth of Andres Bonifacio, founder of the revolutionary organization Katipunan and considered to be the father of the Philippine Revolution. The occasion would be celebrated in different ways. The government would mark this solemn occasion by having wreath laying programs with simple ceremonies and speeches in places and monuments celebrating Bonifacio’s heroism. On the other hand, nationalist and progressive organizations would commemorate this day by holding programs and demonstrations.

One such monument, where the two celebrations usually both take place one after the other, is the Bonifacio Monument located in the middle of Liwasang Bonifacio – the former Plaza Lawton.

In the spirit of celebrating Bonifacio Day, Renacimiento Manila would like to educate readers as to the history of this plaza, how it evolved from a foreign ghetto into a park and how Bonifacio’s name and monument would make it a platform and take off point for the manifestation of the grievances of the people.

A Marketplace and Ghetto

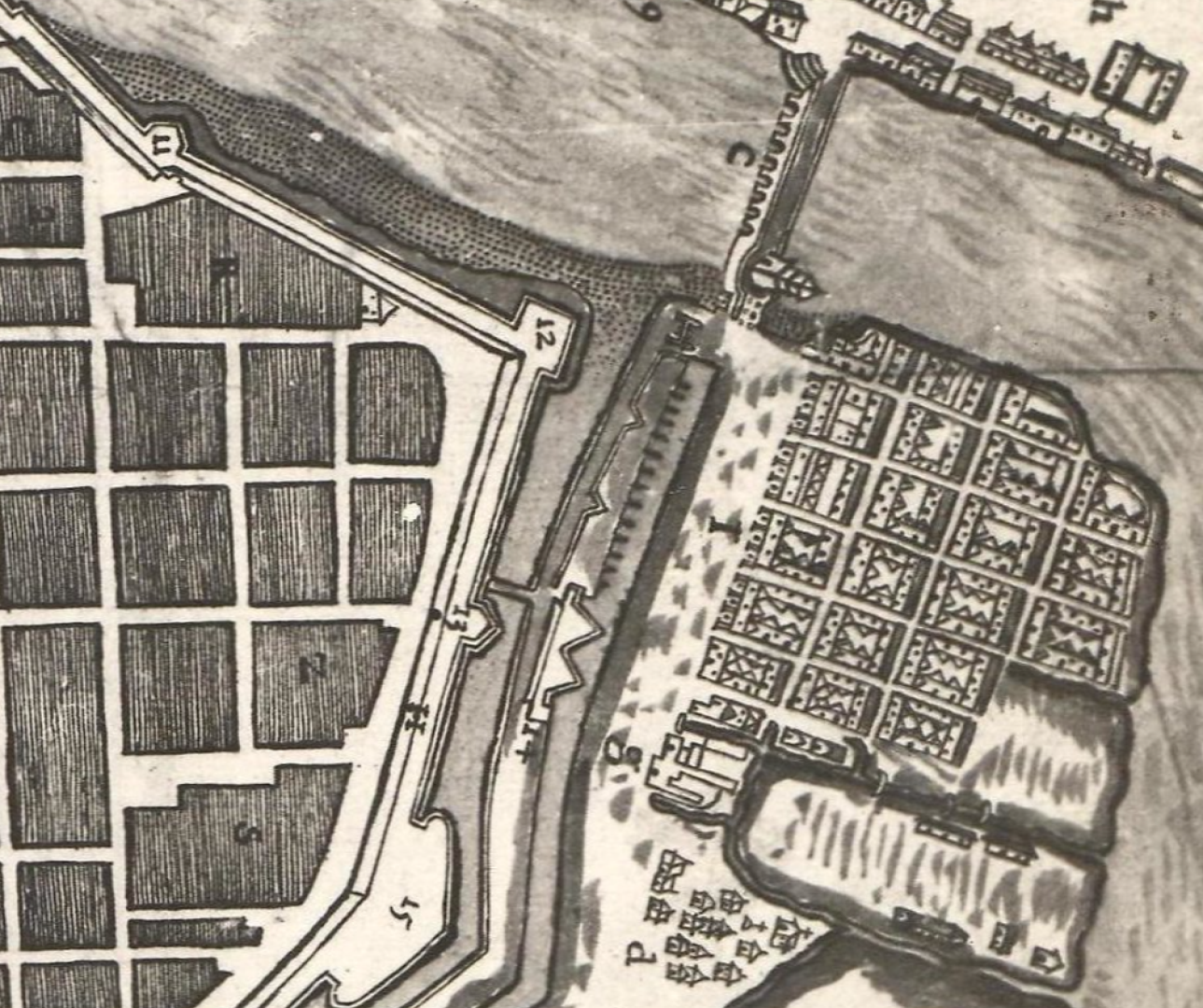

The area now occupied by Liwasang Bonifacio and the Post Office Building used to be the site of the Parian de Arroceros. The Parian was the marketplace of Intramuros and Manila’s early economic and trading hub. It was also a Chinese ghetto, a place where a minority group such as the Chinese were confine, closely guarded by the Spanish. The district occupied the area east of Intramuros, in what was the first bend of the Pasig River. The community eventually grew, having its own parish church, cemetery and stores like the Arroceros Rice Market.

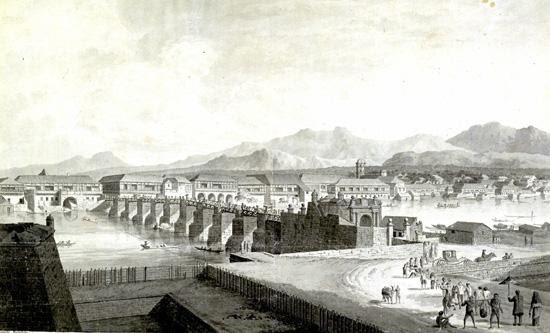

North of the community stood Manila’s oldest bridge and river crossing, the Puente Grande. The bridge was built in the 17th century or the 1600’s with contributions from the “Sangleys” or the Chinese traders. On the southern end of the bridge, the Spaniards erected a defensive structure. It was a small bastion that acted as a defense for anyone trying to attack the bridge. This was called the Fortin.

The decades after the British occupation of 1762-1764 was a tumultuous one for the Chinese community. Their closeness and support for the British would provide the Spanish with justification for their deportation and subsequent ban from the country. As for the Parian itself, its close proximity to the walls meant that it was a security threat to Intramuros, and so it was demolished. By the 1800’s the former Chinese ghetto and marketplace had become a vast marshy open field – with clear line of sight for Manila’s cannons.

From Ghetto to Botanical Gardens

The Spaniards would soon erect a few structures in the area of the former Parian. They filled the area with several barracks. One such barracks stood was the Infantry Barracks near the Fortin of the Puente Grande, in the area occupied by the Post Office Building today.

The open space in front of the barracks and the fortin came to be known as the Plaza del Fortin.

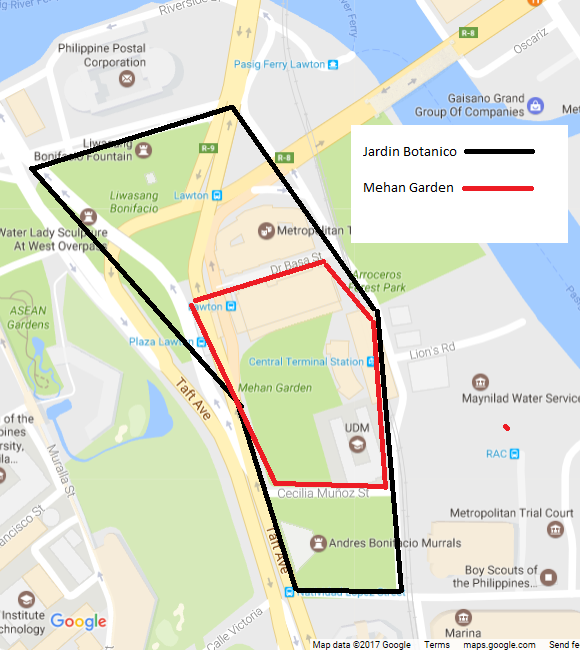

In 1858, Governor General Fernando de Norzagaray designated five hectares of the Arroceros field as parkland. It would eventually be developed into Manila’s Botanical Gardens or Jardin Botanico.

The Jardin Botanico featured flora and fauna, and was Manila’s zoo. It soon became part of Manila’s promenade and growing number of parks.

The northern portion of the garden was bisected by a road to Quiapo which crossed the Pasig River through the Puente de Claveria or the Puente Colgante which had been built earlier in 1852.

The earthquake of 1863 would destroy the Puente Grande, and the bridge was soon demolished and replaced by the Puente de España. But the name Plaza del Fortin remained.

A Plaza for an American General

When the Americans came, they converted the botanical gardens and zoo into a public park. This would become the Mehan Gardens, named after John C. Mehan, Manila’s sanitation officer at the time. Not included as part of the new Mehan Gardens was the area near the Fortin Barracks and Plaza.

The area was soon bisected by several roads coming from the three bridges that met near the area – Joes Bridge, Santa Cruz Bridge and the Colgante.

The barracks was turned into the Post Office building by the Americans. The location was ideal because at the time mail was delivered by steamers and boats and the location of the barracks near the Pasig River made it ideal for bringing in mail.

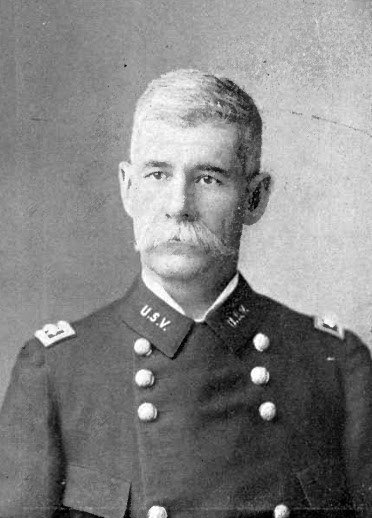

In the early 1900’s the plaza was renamed Plaza Lawton, in honor of Major General Henry Lawton. General Lawton fought in the US Civil War and was part of the “Indian Wars” waged by the US against the Native Americans such as the Apache nation. Lawton famously captured Apache chief Geronimo after wearing down the Apaches in a determined pursuit. He fought in Cuba against Spain in 1898 and was sent to Manila to fight the Filipino republican armies of Aguinaldo.

Tenacious as ever, Lawton did recognize the bravery of the Filipino “insurgents” that he was fighting, given the poor material condition of the republican armies. In the Battle of San Mateo (in the area part today of Bagong Silangan, Quezon City), Lawton was mortally wounded by a Filipino sniper who was part of the opposing troops led, coincidentally, by General Licerio Geronimo. He died soon after and was brought home to the US. Lawton was the highest ranking officer to fall in the American side during the Filipino-American War.

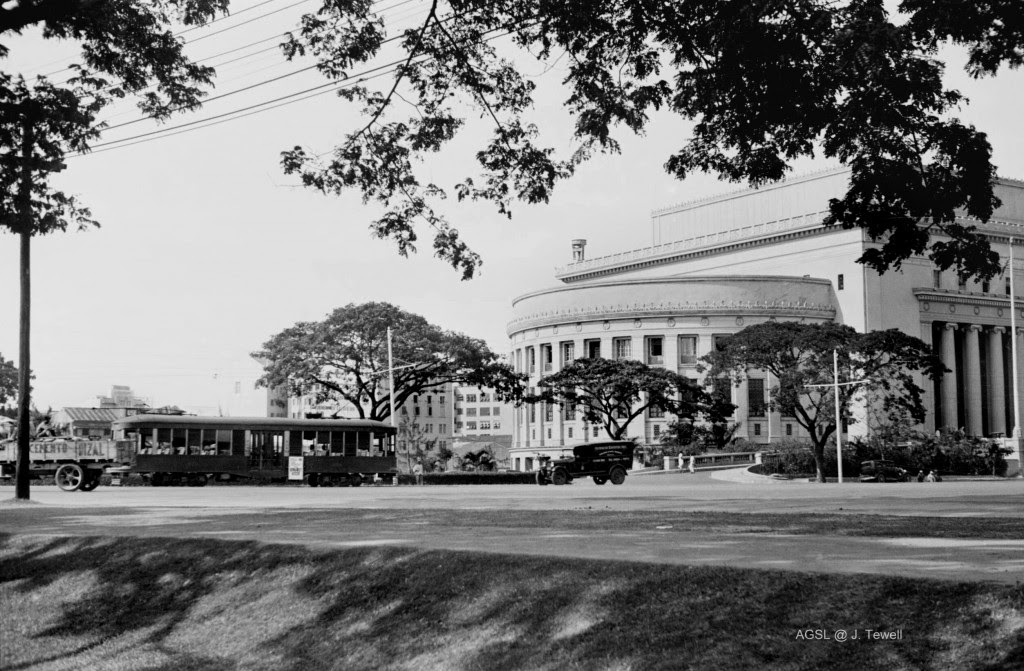

The Plaza del Fortin was renamed in his honor in the early 1900’s. The area soon became a busy and important crossing for traffic going and coming from the three bridges. The Plaza would eventually be dominated by the imposing Manila Post Office Building, whose neoclassical edifice by Juan Arellano would come to define the vista of the Plaza.

The Plaza also became a stop for the tranvia or tram cars which once dominated Manila’s streets.

A Plaza for a Revolutionary

The Second World war left Plaza Lawton and the surrounding buildings in ruins. Gone was the tranvia the postwar years. It would soon be replaced by jeepneys and, more importantly, the buses. As the former moat outside of Intramuros near Letran became a bus depot and terminal, Lawton would soon be a major bus stop for city and provincial buses (which continues to this day).

In 1963, the now independent Philippine Republic celebrated the centenary of Andres Bonifacio’s birth. In order of honoring the “father of the Philippine revolution”, it was decided that Plaza Lawton would be renamed into Liwasang Bonifacio. At the center of this plaza a new Andres Bonifacio monument was erected, designed by esteemed sculptor and national artist Guillermo Tolentino.

The 1960’s would witness a nationalist reawakening that was most profound among the youth. This would give birth to student and youth activism which would in turn manifest across all sectors. As nationalist and progressive groups emerged, they saw more and more the importance of Bonifacio’s revolutionary role and the need to continue the “unfinished” revolution that he started.

Demonstrations, camp outs and other protest actions would become a frequent site in the Liwasang Bonifacio. From the dark days of Martial Law, to the post dictatorship years, the Liwasan became a stage for the grievances of the people, all taking place under the gaze of the great revolutionary.

The plaza is designated as a freedom park, where demonstrations could be held without permits as a recognition of the important role of civil action and activism in the development of a democracy.

Liwasang Bonifacio has seen neglect through the years, overshadowed by dingy flyovers, and being turned into a terminal. But the city government today is showing signs that it has the intent of sprucing up the place. Hopefully, not by placing more grotesque sculptures or pouring more concrete, but by improving the park’s landscape and making it a healthy environment for the citizens.

A freedom park enjoyed and treasured by the people, and maintained by a state that owes its independence as a result of people like Andres Bonifacio, is a fitting tribute to the man, his compatriots and their ideals for independence and freedom.

References

Wolff, L. (1961). Little Brown Brother: How the United States Purchased and Pacified the Philippine Islands at the Century’s Turn. Doubleday.

Midnight Library Web (2017) Jardin Botanico. WordPress

Urban Roamer (2011) The Liwasan formerly known as Lawton.

Lou Gopal (2013) Jones Bridge. Manila Nostalgia

Lou Gopal (2013) Puente Colgante – Insular Ice Plant and Cold Storage. Manila Nostalgia

Text by Diego Gabriel Torres

Illustration by Jeremiah Inocencio, Renacimiento Manila

All Rights Reserved.

The Renacimiento Movement. What, then, is the Renacimiento Movement? The movement is the core philosophy of the organization. It is founded on the reality that heritage is a cornerstone of holistic development and that it is indispensable in ensuring quality of life. As such, cultural revival is necessary for the promotion of heritage in the national agenda. Heritage should be driven by the people, regardless of race, gender, creed, or religion. This cultural revival can be achieved through the following ways: government support, the advancement of private initiatives, and the engagement of the people.

Leave a comment