Angela Piguing, Ken Tatlonghari

21 February 2021

What is considered Filipiñiana attire today has always been attributed to the baro’t saya. The baro’t saya, on the other hand, has seen itself reimagined through the centuries, shaped by norms and possibly other unsaid implications. In line with the month of the Manila Carnival, the now-least-worn style of the baro’t saya—here, the traje de mestiza is to be inspected from the closet of centuries.

Dress of the Misses

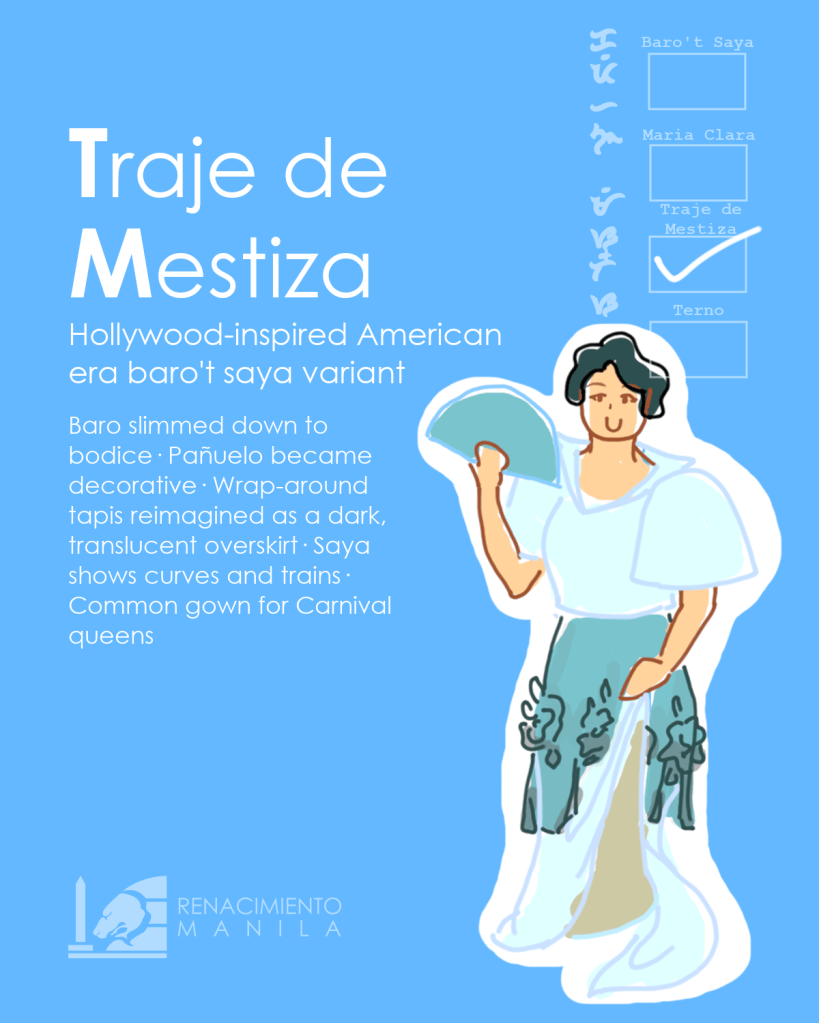

Although this may also refer to the female attire (dubbed the “Maria Clara”) during the Spanish era, the traje de mestiza became a prominent style of Filipiñiana attire during the American colonial era. Thus the pre war Filipiñiana could be best referred to with that term. The traje de mestiza features a somewhat-thinner pañuelo, a wider neckline, a clinging bodice, and the sleeves are noticeably wider. Such sleek features were influenced by Hollywood female stars and the Gibson Girl style. With the colonial style having changed the tides of norms, the conservative Maria Clara dress has taken a more open shape.

The traje de mestiza had become stylish in its heyday. Because the material used for the upper and lower apparel are similar, it is sometimes considered as “terno”. Putting emphasis on the hourglass figure and the shapely features of the ladies, it had become a staple for Manila Carnival candidates, aside from other Asian-inspired costumes.

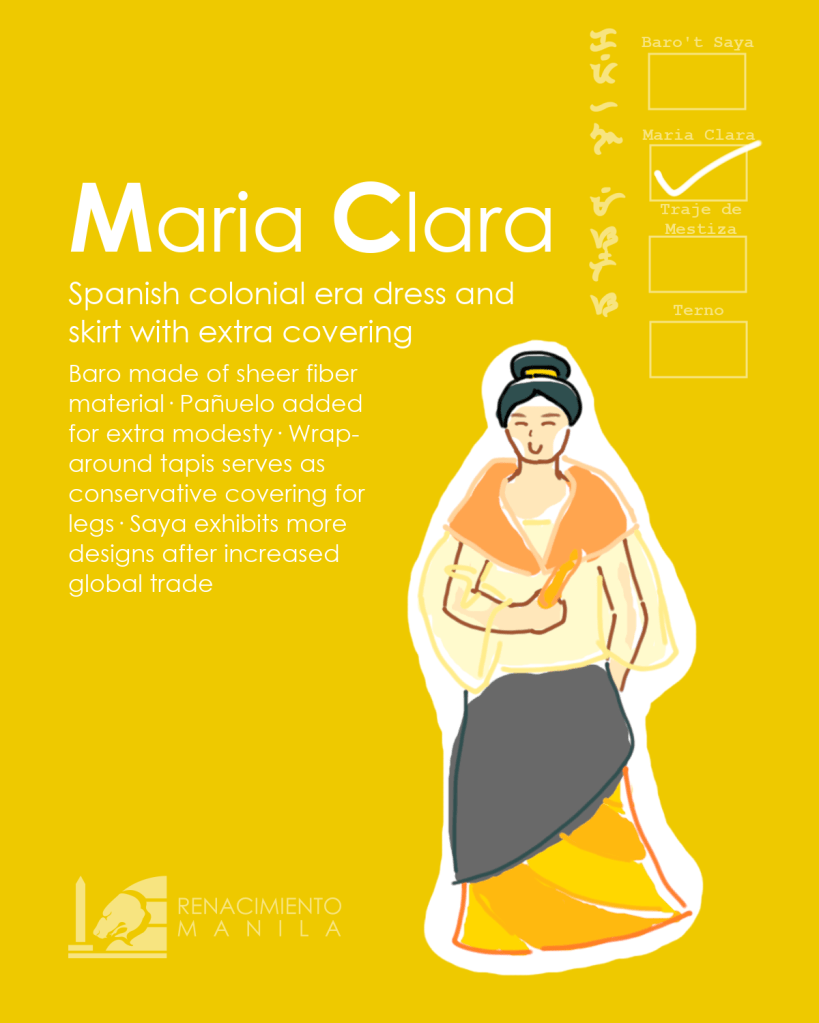

The Maria Clara dress called for a highly conservative style during the Spanish colonial era, when “showing off extra skin” was considered taboo. But by the time of Americanization, the traje de mestiza had replaced the need for “extra covering” and would have been considered “daring” from the older perspective.

During its heyday, the traje de mestiza has found itself used not only as formal wear, but also for the dailies; a direct wink to the widespread usage of the traditional baro’t saya.

The baro’t saya and its prewar successors has found itself in variety and practical usage. In our case today, is it about the lack of comfort brought by the clothing style that brought the Filipiñiana reserved for formal events? Connecting the dots of identity through hems may give us an idea of what makes up a true Filipiñiana attire.

Stitching parts of the “mixed dress”

The baro’t saya used to be the basic daily wear of Filipino women, where the basic elements of its successors came from. The baro or blouse used to be straight and loose, and was largely unadorned until the expansion of global trade and stronger Spanish influence brought about resources to adorn the ensemble, later on evolving to the Maria Clara style, named after Jose Rizal’s tragic character of the same name.

Of all elements in the Filipiñiana, the butterfly or bell sleeves remained a defining feature. Made of local fibers, the baro has a notable translucence and stiffness. Because of this, the pañuelo, alampay, or fichu served as modesty for the upper bosom. It is generously decorated with intricate lace or embroidery work.

Image courtesy of Leo Cloma via Flickr.

Image courtesy of John Tewell via Flickr.

Alternatively the pañuelo can be used as a headband. Fernando Amorsolo’s depiction of rural life showcases this in bright colors. Without the pañuelo above the chest, a camison is worn as an undergarment instead.

Meanwhile, the saya used to be a wrap-around skirt, akin to its other Malay counterparts. A baro’t saya whose skirt is shorter can be referred to as the “Balintawak” style. It became a defined variant of the baro’t saya during the 1930’s. As it requires lesser lengths of cloth, it was favored by ladies who go on trips with its knee-length skirt.

The tapis serves as an extra overskirt or apron. It adds an extra layer of modesty for the otherwise sheer material of the saya. For the case of the traje de mestiza, this has developed into the sobrefalda or a lacy outer skirt that adds a design in contrast to a light-colored saya.

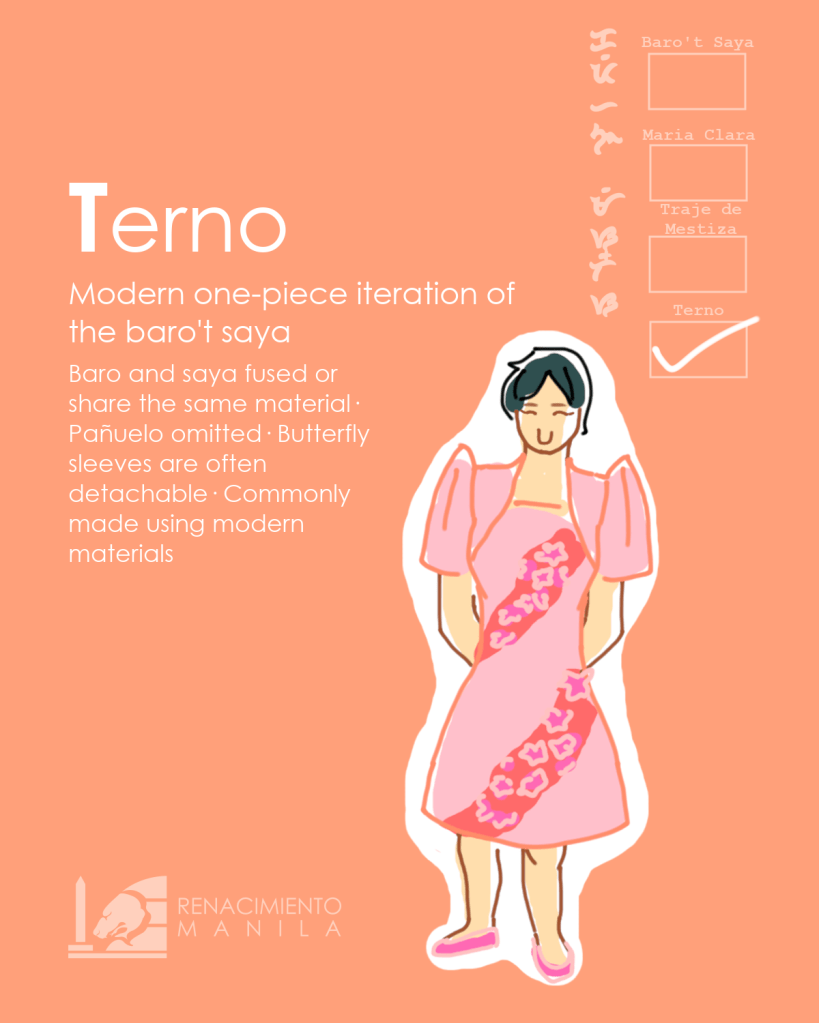

The terno has become a style of its own from being a description of a baro’t saya being of identical style and material. Although the term has been in use as early as in the Spanish period (terno meaning “matching” in Spanish), it has become the popularized term for the streamlined, one-piece incarnation of the baro’t saya we know today.

Redressing with modernity

In our modern era, the national costume has usually been reserved for formal occasions or for cultural events. But in Japan and South Korea, there have been efforts to celebrate the kimono and the hanbok respectively as street fashion. South Korea also incentivizes this by permitting hanbok wearers free entrance to Seoul’s 5 palaces. Perhaps one day Intramuros will also provide free access to certain places or events for wearers of the Filipiñiana and this would also contribute to instilling nationalism.

The Filipiniana costume has several variations, and one can always choose the style which best fits one’s taste. Elements from Filipino design can also be incorporated into casual wear and this is another opportunity to celebrate Philippine culture. We have many options to choose from how we can celebrate identity and fashion, best sewn with historical context.

References

- Center for Southeast Asian Studies (n.d.) Baro’t Saya. Northern Illinois University

- Center for Southeast Asian Studies (n.d.) Maria Clara. Northern Illinois University

- Center for Southeast Asian Studies (n.d.) Traje de Mestiza. Northern Illinois University

- Center for Southeast Asian Studies (n.d.) Balintawak Dress. Northern Illinois University

- Center for Southeast Asian Studies (n.d.) Terno. Northern Illinois University

- The Philippine Folk Life Museum Foundation (n.d.) Baro’t Saya.

- The Philippine Folk Life Museum Foundation (n.d.) Traje de Mestiza

- Sison, S. (2019) Here’s Everything You Need to Know About the Filipiniana Attire. Preview PH

- San Jose, C. (2019) The terno is back from the baul. Now what? Nolisoli PH.

The Renacimiento Movement. What, then, is the Renacimiento Movement? The movement is the core philosophy of the organization. It is founded on the reality that heritage is a cornerstone of holistic development and that it is indispensable in ensuring quality of life. As such, cultural revival is necessary for the promotion of heritage in the national agenda. Heritage should be driven by the people, regardless of race, gender, creed, or religion. This cultural revival can be achieved through the following ways: government support, the advancement of private initiatives, and the engagement of the people.

Leave a comment