Diego Torres; art by Dom Quiroga

23 March 2021

In celebrating National Women’s Month this March, we remember and celebrate the historic and present role of women in shaping our nation and our communities.

As a community, we remember the great deeds of individuals through different ways. We set up monuments and memorials, put up historic plaques, name buildings in their honor and we name plazas and streets after them. This is, for the most part, driven by our desire to always remember the name of such illustrious individuals.

Manila’s cityscape is no different. Here and there, we will see monuments, markers, and other memorials to the great and noble who have been important actors in the story of the city and our nation.

We focus today on streets and plazas named in honor of women. You will be surprised to find out that there are only a handful of places in Manila named after women. The name of saints, religious themes, Spanish words, male heroes, statesmen and, sadly, politicos are everywhere, but only a few streets and plaza are named in honor of women.

Here are some of these places that have been named in memory of Her, and her deeds for the nation:

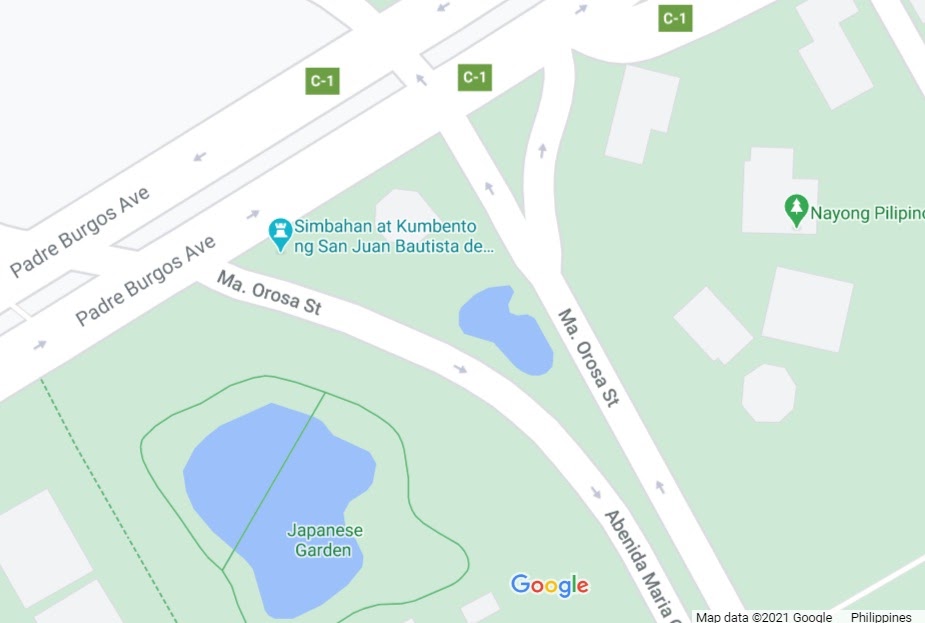

Avenida Maria Orosa and Triangle Garden

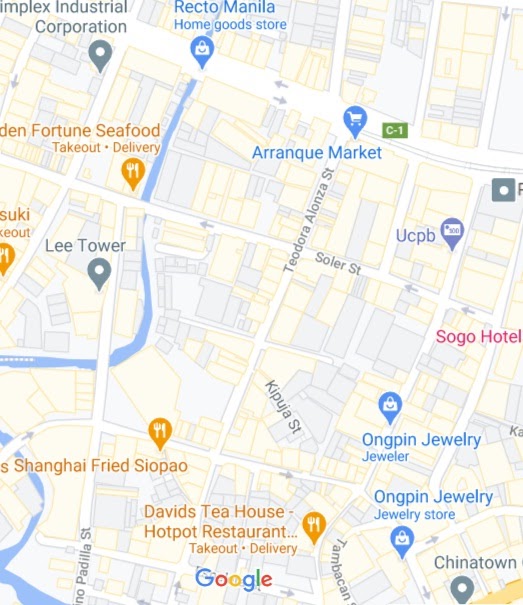

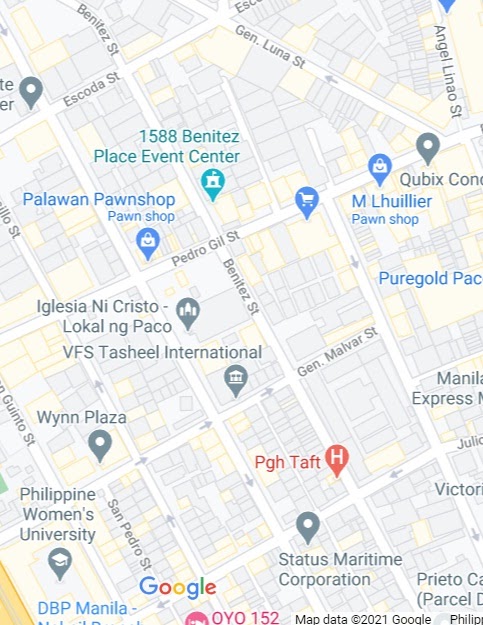

Right: Ma. Orosa St. and the triangle garden from Google Maps

Located at: Ermita

Formerly known as: Calle Florida

This street and triangular garden (which is part of the center island) is named after the chemist and food technologist Maria Ylagan Orosa.

A native of Taal, Batangas, Orosa was born in November 29, 1892. She grew up during a period and in a place that was rocked by the great nationalist upheavals of that time – the Philippine Revolution and Filipino-American War. Her father, Simplicio Orosa y Agonicllo, was a nationalist and supporter of the revolution. He campaigned for Philippines independence in the early years of American colonial rule.

Maria Orosa entered the University of the Philippines in 1915 as a government scholar. But seeing her talents, she was sent to the University of Washington in Seattle (USA) in 1916. There she studied pharmaceutical chemistry and food chemistry and later earned a master’s degree in chemistry.

Maria Orosa returned to the Philippines and worked in the government as a chemist of the Bureau of Science and Bureau of Plant Industry.

She worked on canning and food preservation, preserving fruits and canning local food produce as a way of relying less on imported goods and making canned produce cheaper. She worked with domestic products and applied preservation techniques like canning, dehydrating and fermenting. Maria Orosa was particularly keen in addressing the problem of malnutrition.

Maria Orosa is famous for inventing the banana ketchup, which was intended to be a substitute for imported ketchup. She also worked on soyalac, a nutritious drink made from soy beans, and also powdered calamansi juice. Her work on canning mangoes helped in the export of mangoes to other countries.

During the World War 2, Maria Orosa joined the resistance against the Japanese. She joined the Marking’s Guerillas and became a captain. She fought the Japanese in her laboratory, working to produce food products that were used by the guerillas or smuggled to prisoners inside Santo Tomas Internment Camp. She also did her best to save people from the Japanese.

Even when Manila was being torn apart by Japanese barbarity and American shelling in 1945, Maria Orosa stayed in her lab at the Bureau of Plant Industry in Malate. She was hit by shrapnel when the building was shelled. She was then taken to Malate Remedios Hospital, which was also shelled.

It was there that the nationalist and patriotic chemist, along with other civilians, perished. Her remains are yet to be found.

In honor of her, Florida Street was renamed Maria Orosa Avenue. Long forgotten, interest in Maria Orosa and her legacy were renewed when a memorial to her and other victims was excavated in the former site of the Remedios Hospital in 2020. The city government is also improving the center island triangle as a park with a memorial to Maria Orosa.

Plaza Salamanca

Right: Plaza Salamanca as seen from Google Maps

Located at: Ermita

Most people would seldom notice this small piece of triangular greenery located close to the UN Avenue LRT Station and the Central Methodist Church. This plaza is known as Plaza Salamanca, dedicated to Olivia Salamanca, M.D.

Olivia Salamanca was born in San Roque, Cavite in 1889, the daughter of a pharmacist. As a young child, Olivia was exceptionally bright, and even artistically inclined.

In 1905, she was chosen as part of a delegation of government scholars who will be sent to study in the United States. She first studied in St. Paul, Minnesota after which she entered the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia. The 20 year old Olivia graduated in 1910 with an average grade of “A”.

She was the first Caviteña to become a doctor and the second Filipina doctor – the first being Honoria Acosta-Sison who earned her degree a year earlier in 1909.

Olivia returned to the Philippines in 1910, where she joined the Philippine Anti-tuberculosis Society. But that same year, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis which at the time was almost a death sentence. She was assigned to a hospital in Baguio in 1911, where she busied herself taking strolls, reading books, doing crafts and even learning French. By 1913, her condition had worsened. She was brought back to Manila to be treated at the Philippine General Hospital.

The Philippine’s second female doctor succumbed to tuberculosis in 1913, at the age of 24.

Plaza Librada Avelino

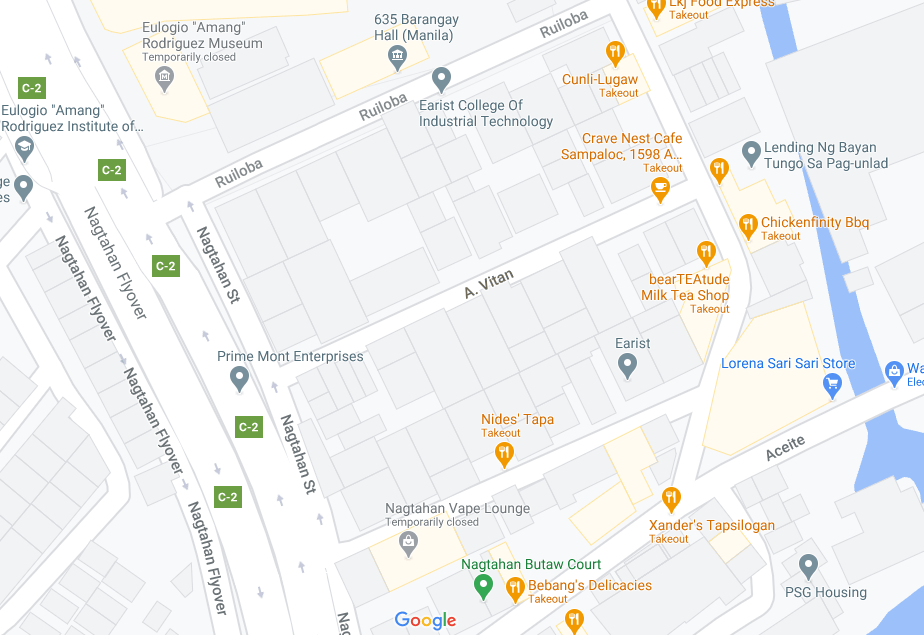

Right: The former site of Plaza Avelino, near what is colloquially referred to as “Nagtahan”

Located at: Sampaloc

Formerly known as: Rotonda de Sampaloc

The area today is a dystopian landscape of flyovers and tangled highways where several roads converge. It is a classic image of a drab inner city highway dominated cityscape.

But this area was once a scenic rotunda. In the Spanish period, the area where the Paseo de Sampaloc, Nagtahan Road and Marikina Road met was known as the Sampaloc Rotonda. This roundabout was graced by the Carriedo Fountain, a water fixture erected in honor of the man who bequeathed his money for Manila’s first modern water system – Don Francisco Carriedo.

But in the 20th century, the Rotonda was renamed Plaza Librada Avelino, in honor of a passionate educator.

Librada Avelino, called “Ada” by friends, was born in Quiapo in 1873. She grew up on Pandacan, then a sleepy island suburb south of the Pasig River from San Miguel. She was a passionate student, and hungered for knowledge beyond what was deemed acceptable for women at the time. As a result, she studied geography, and advanced mathematics during her primary schooling. She eventually took up education and she passed the civil exam in 1889, becoming an educator.

She opened a free school in Pandacan, but even so, she took up courses at La Concordia and the Assumption Convent, which would give her certification to teach high school. The Revolution of 1896 and subsequent American aggression disrupted her practice.

Following the American conquest, a new set of rules were implemented regarding schools, which included the teaching of English. Avelino studied English with American teachers in the Pandacan girl’s school. She later went to Hong Kong where she furthered her education in English.

By 1907, Avelino had only one thing in her mind, and that was the establishment of a new school for women. Together with Carmen de Luna (whom she had met earlier when she was still running her free school in Pandacan), she approached several women educators in order to realize her dream. With an investment of Php 750, they opened their new school in Calle Azcarraga (CM. Recto today), in June 1907. The school was called the Centro Escolar de Señoritas, with 27 students.

Through the years, Avelino and her colleagues worked hard to expand the school, which would gradually offer college degrees.

The Centro Escolar de Señoritas was the first non-sectarian school in the country.

Avelino was a liberal, a feminist and a modernist, but she was also a nationalist. She labored her whole life to give women the same educational opportunities as men.

By 1932, the Centro Escolar de Señoritas became the Central Escolar University.

She never married and spent her entire life advancing the opportunities of women via education. She died of stomach cancer in 1934. At the time of her death the schools she had started had become the largest women’s institution in the country, with 20,000 students.

In addition to the Rotonda, a school in Tondo and a street in Pandacan were also named in her honor.

Sadly, the volume of traffic in the rotunda increased through the decades as it became a busy intersection. In the 1970s, the fountain was removed and the streets were widened. New flyovers were later erected all over the place. The plaza is now an intersection.

Escoda Street

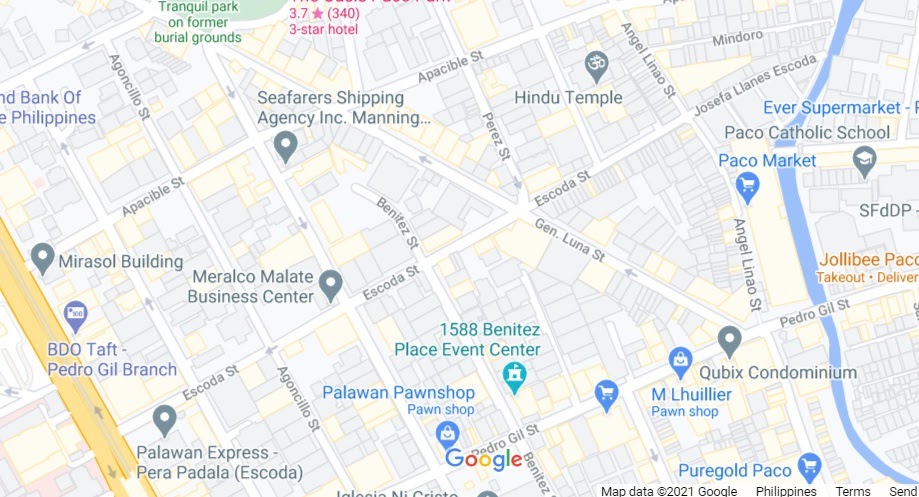

Right: Escoda Street seen from Google Maps

Located at: Malate-Paco

Formerly known as: Calle California

This street, which starts from Taft Avenue just across PGH and continues east towards Paco, is named in honor of Josefa Llanes Escoda, a suffragist, social worker and a martyr of the Japanese occupation.

Josefa was born in Dingras, Ilocos Norte in 1898. She studied teaching and education at the Philippine Normal School in Manila, where she graduated with honors in 1922. She became executive secretary of the National Federation of Women’s Clubs (NFWC) in 1923, where she advanced her advocacy for women’s involvement in governance as well the right of women to vote. Josefa was keen in advancing maternal health as well as child welfare.

She went on several trips abroad to the USA, where she would later train under the Boy Scouts. Upon her return to the Philippines in 1940, she, together with then NFWC President Pilar Hidalgo-Lim, established the Girl Scouts of the Philippines.

When the Japanese conquered the Philippines, Josefa and her husband Antonio Escoda, helped in aiding the prisoners of Bataan as well as civilian internees at Santo Tomas Internment Camp. The couple also supported underground resistance groups against the Japanese, which led their arrest in 1944.

Josefa was last seen at the Far Eastern University compound (used then by the Japanese military) in 1945, alive but visibly abused by her captors.

The Ilocana suffragist and feminist was martyred by the Japanese in the closing days of their brutal occupation in Manila. Her remains are lost in the many mass graves of victims of Japanese atrocities.

Natividad Lopez St.

Right: The eponymous street as seen from Google Maps

Located at: Ermita

Formerly known as: Calle Concepcion

The street that runs from Kartilya Park beside Manila City Hall, and continues all the way past Arroceros and SM Manila to the foot of Ayala Bridge is actually named in honor of the first female lawyer in the Philippines.

Natividad was not the first Filipina to pass the bar, but she was the first Filipina to practice law and handle cases when she became a lawyer in 1914.

In addition to being a lawyer, she was also an outspoken advocate for women’s suffrage, and even went to Congress to give speeches concerning women’s rights.

She married Domingo Lopez, a lawyer who was also governor of Tayabas province (Quezon today). Natividad used her husband’s political rallies to give speeches regarding women’s votes and women’s rights.

She eventually became the first female judge in the Philippines when she became Manila’s executive judge in 1934. As a judge in Manila, she believed earnestly that the poor must benefit the most from the law. During the war she would dismiss cases against guerillas, most of home have been tortured by the Japanese.

Natividad would go on to become a judge of the Domestic Relations Court and in 1961 she became a judge of the Court of Appeals, the first woman to do so.

Madre Ignacia St.

Right: Madre Ignacia Street from Google Maps

Located at: Malate

Formerly known as: Calle Carolina

A street that runs parallel to M.H. del Pilar and A. Mabini are named in honor of Mother Ignacia del Espiritu Santo, a religious sister who lived in 17th century Manila.

Ignacia was the daughter of a Filipina and a Chinese couple from Binondo. She was baptized in 1663 at the Dominican church in the Parian de los Chinos, the old Chinese quarter of Manila. Growing up, she became very pious and religious, and after seeking spiritual counsel from a Jesuit priest she decided to follow the example of St. Ignatius de Loyola and dedicated her life in the service of God.

In defiance of a Spanish law that forbade natives from entering the convent, Ignacia decided to start living in seclusion in a house located close to the First Jesuit Compound in Intramuros. Guided by a Jesuit priest, she began to live her life in prayer and pious labor. Eventually, native women who were interested in religious life joined her. She and her companions developed rules and regulations for their spiritual group, which they came to become the Beatas de la Virgen Maria, with the foundation of their congregation dated as 1684. She completed the necessary documents in 1726 and submitted them to the Archdiocese of Manila. In 1732, their religious congregation was recognized, a triumph for native women who wanted to express their religious beliefs.

The compound of the Beatas in Intramuros came to be known as the Beaterio de la Compania de Jesus, due to its proximity to the Jesuit compound.

Mother Ignacia died on the altar rail of San Ignacio Church while taking communion in 1748. She was 85 years old, and had lived her life dedicated to her religious beliefs.

The Beaterio still exists to this day, surviving both the expulsion of their Jesuit spiritual guides in 1768 and the destruction of their convent in 1945. They are located today in Quezon City and are now called the Religious of the Virgin Mary (RVM).

Mother Ignacia has also been bestowed with the title venerable in 2008.

There are also other streets in Manila named after women:

Pilar Hidalgo-Lim St.

Located at: Malate

Formerly known as: Calle Indiana

Renamed after Pilar Hidalgo-Lim, an educator and women’s advocate from Boac, Marinduque. Together with Josefa Llanes-Escoda, she founded the Girl Scouts of the Philippines in 1940. She was also the third president of Centro Escolar University, managing the university in the post-war years. She was the wife of Generel Vicente Lim, a commander during World War 2 who was executed by the Japanese.

Francisca Tirona Benitez St.

Located at: Malate-Paco

Formerly known as: Calle Kansas

Renamed after the Caviteña educator, Francisca Benitez. After graduating from the Philippine Normal School, she taught in several schools in Manila. In 1919, she and six companions established the Philippine Women’s College (now Phil. Women’s University), eventually becoming its president.

She was also a civic leader and she established numerous institutions for women.

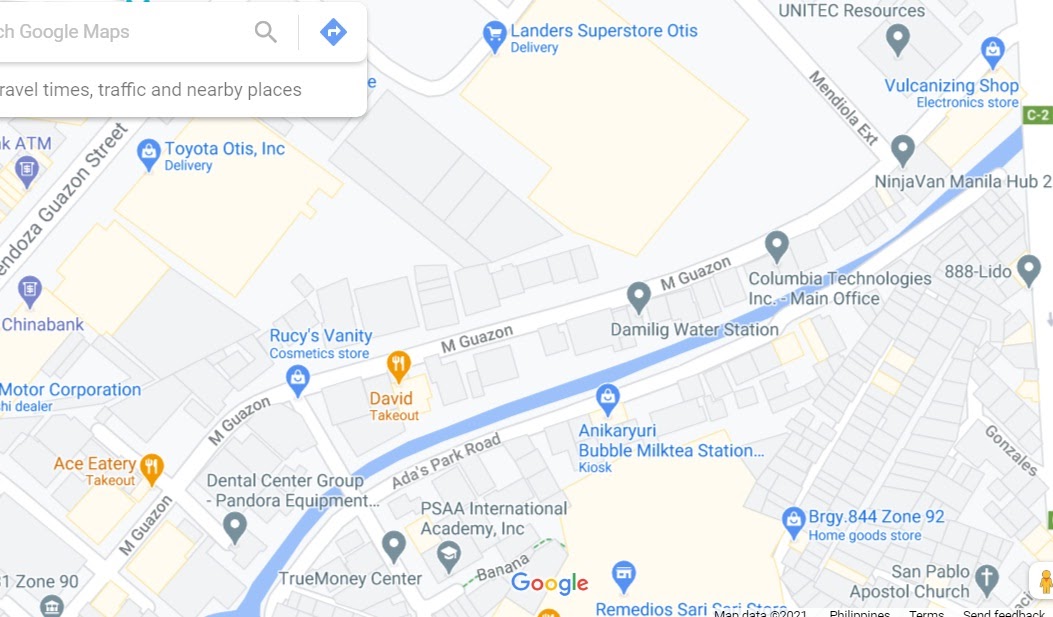

Paz Mendoza Guazon St.

Located at: Paco

Formerly known as: Calle Otis

Renamed in honor of Dr. Maria Paz Mendoza Guazon, the first woman to graduate from the first medical school in the country, the UP College of Medicine, where she graduated in 1912. She was the first female member of the UP Board of Regents, becoming its member numerous times, and she was also sent abroad by the government on educational missions. She was also a vocal advocate for Philippine Independence and the women’s suffrage movement. In her capacity as a pathologist, she was the first to call attention to “bangungut” as a medical condition.

Dr. Concepcion Aguila

Located at: Quiapo-San Miguel

Formerly known as: Calle Tuberias

Renamed after educator Dr. Concepcion Aguila. Originally from San Jose, Batangas, she became a kindergarten teacher at Centro Escolar. She took up law at the Philippine Law School and in 1926, she passed the bar exam. She would go on to be involved in numerous educational committees in the early days of the new republic.

Reina Regente

Located at: Binondo

Formerly known as: Calle Reina Cristina

Name after the Queen Regent Maria Cristina, who ruled as queen regent of Spain from 1885 to 1902. As regent to a young king, she oversaw the loss of most Spanish Overseas territories resulting from Spain’s defeat in the Spanish-American War.

Engracia Cruz-Reyes St.

Located at: Ermita

Formerly known as: Calle Arkansas

Filipina chef and entrepreneur who established the famous The Aristocrat restaurant chain. A native of Navotas, she began her culinary career assisting her family in peddling street food. She later opened a small carinderia in Ermita, as well as selling food in using a car. In 1936, she established a rolling restaurant in a truck, which she called the Aristocrat. Following the war, she moved the Aristocrat in Malate, where its menu of Filipino food has helped make local cuisines a staple.

Teodora Alonzo

Located at: Binondo

Formerly known as: Calle Arranque

The street was renamed in honor of Teodora Alonzo, the mother of Dr. Jose Rizal

Cecilia Muñoz St.

Located at: Ermita

Formerly known as: Calle Hospital

Named after Cecilia Muñoz-Palma, the first woman to be appointed to the Supreme Court. Although she was appointed by the late dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, Muñoz-Palma would go on to voice out her dissent in various rulings supporting the dictatorship and martial law. Following the overthrow of the dictatorship, Muñoz-Palma became head of the commission that drafted the new constitution.

Andrea Vitan Street

Located at: Sampaloc

Andrea Vitan-Arce was a Filipino teacher and writer, and had served as the first principal of Legarda Elementary School alongside serving as a school teacher for almost 20 years. Some of her works were also featured in the collection “50 Kuwentong Ginto ng 50 Batikang Kuwentista” containing literary works alongside others, curated by Pedrito Reyes. She has also taken part in patriotic movements.

These are just a few of the many stories of women in the bigger story of the Philippine nation. We must do our best to honor their legacy, and remember each and everyone who lived brave and exemplary lives. We must remember them not only during National Women’s Month, but as part of our everyday lives.

Mabuhay ang Kababaihang Pilipino!

The Renacimiento Movement. What, then, is the Renacimiento Movement? The movement is the core philosophy of the organization. It is founded on the reality that heritage is a cornerstone of holistic development and that it is indispensable in ensuring quality of life. As such, cultural revival is necessary for the promotion of heritage in the national agenda. Heritage should be driven by the people, regardless of race, gender, creed, or religion. This cultural revival can be achieved through the following ways: government support, the advancement of private initiatives, and the engagement of the people.

Leave a comment