Ken Tatlonghari

11 April 2021

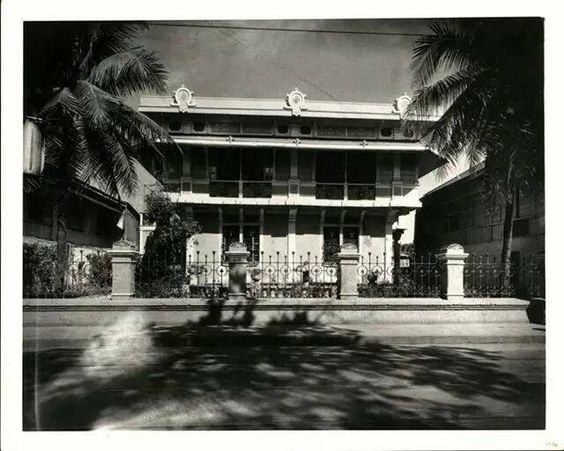

The Zaragoza-Araneta house currently owned by the Sisters of the Holy Face of Jesus was one of the Zaragoza/Araneta houses in Quiapo. It was once used as the consular office of Jose Zaragoza y Aranquizna, representing Ecuador and Liberia.

José Zaragoza was the son of Rafael Zaragoza, Spain’s representative in Nueva Ecija for ensuring Spanish profits from the tobacco monopoly tax. Rafael’s other son was Miguel, and both were born in San Isidro, Nueva Ecija. They were born during a time of economic prosperity brought on by the tobacco industry, the end of the galleon trade (1815) and the opening up of Manila to global trade (1834) which also led to the first Manila Art Academy’s creation (1821-34). Miguel would be ripe for the artistic path as he would recall the “emerald green and lavender sky” of his childhood in Nueva Ecija as inspiration for his art during his twilight years.

His pragmatic father was in fact supportive of Miguel’s artistic bent and was sent to study at the newly opened Ateneo de Manila in Intramuros in 1859 while attending free evening classes at the Academia de Dibujo y Pintura founded by Damian Domingo at 51 Cabildo St. As a criollo, he had to pay for his own materials, while the segregated Indios and mestizos were provided everything free of charge.

Zaragoza’s artistic growth was slow and steady, but sure. At the end of the 1859-60 school year, he garnered the third prize in coloring and drawing from nature and reproductions. He won the 2nd prize for the same class the following year. Finally, he won one of the scholarships granted to two students by the queen of Spain to study in Madrid and another art academy in Europe.

Unfortunately, it was delayed due to the government’s financial problems, but it was finally carried out in 1876 when the Bourbons were restored in Spain through Alfonso XII (son of Isabel II). The second scholarship went to none other than Felix Resurrección Hidalgo.

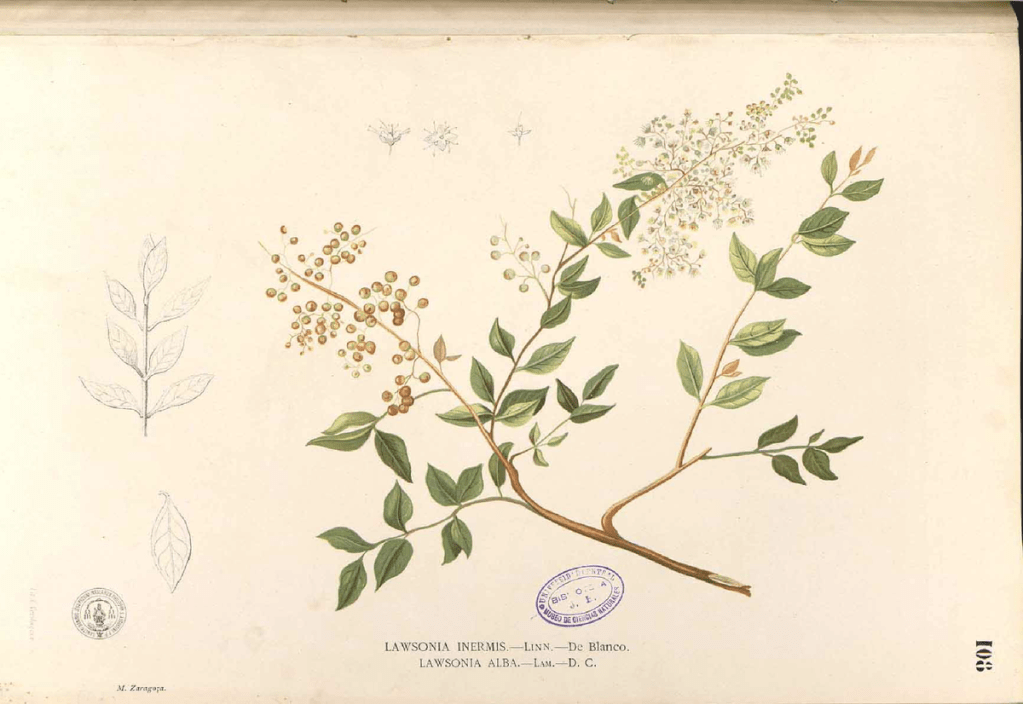

Photo from Flora de Filipinas […] Gran edicion […] [Atlas I]

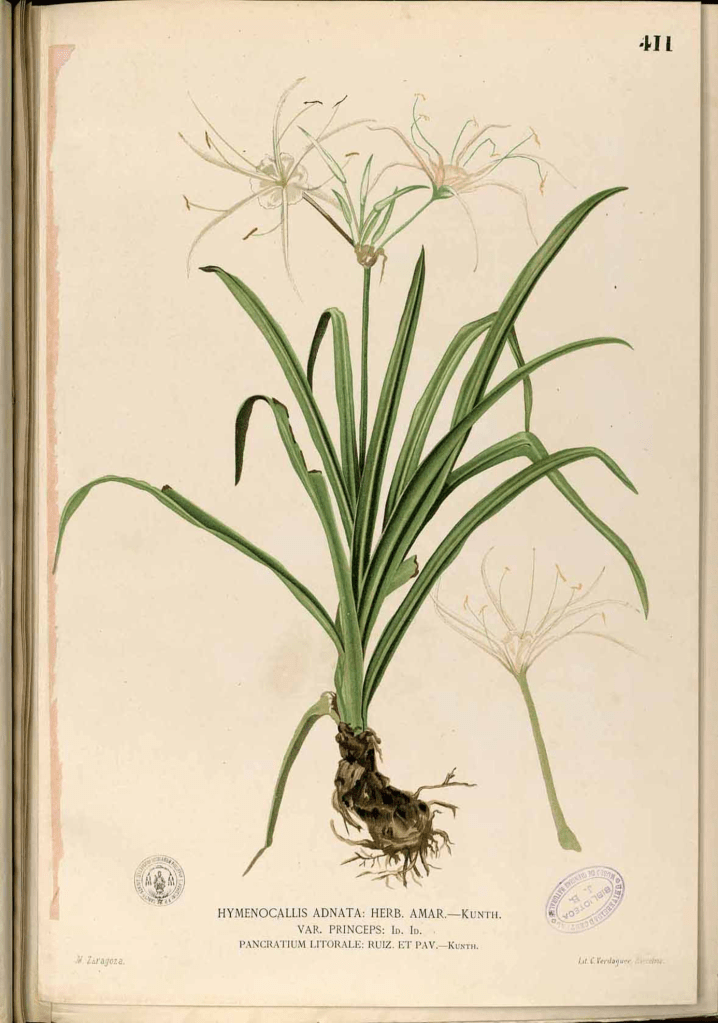

Photo from Flora de Filipinas […] Gran edicion […] [Atlas II].

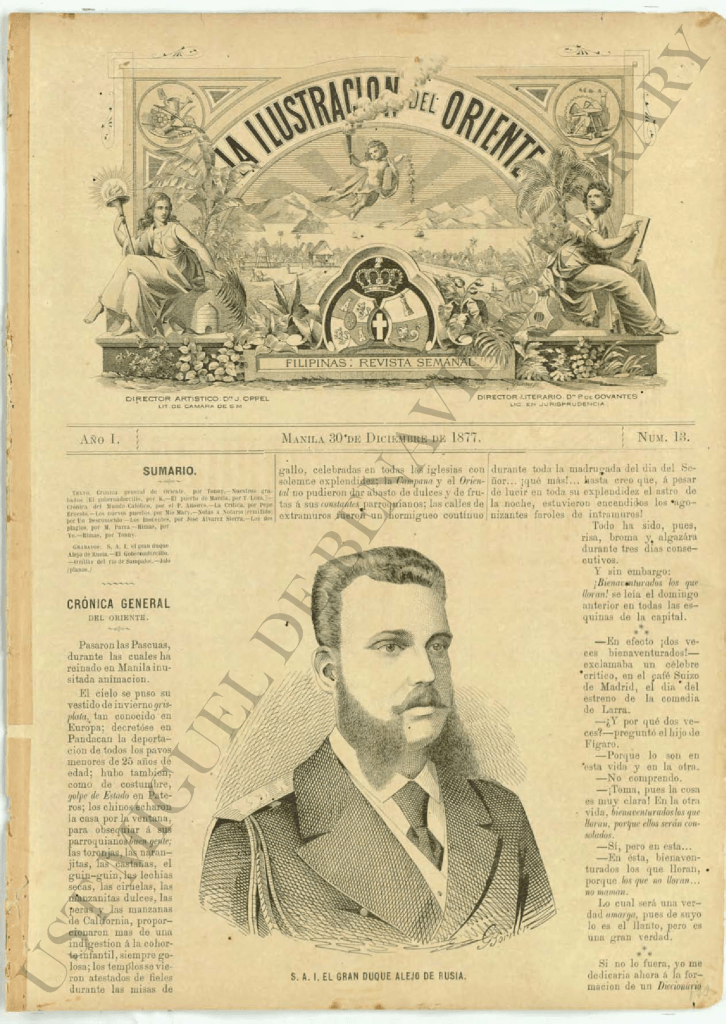

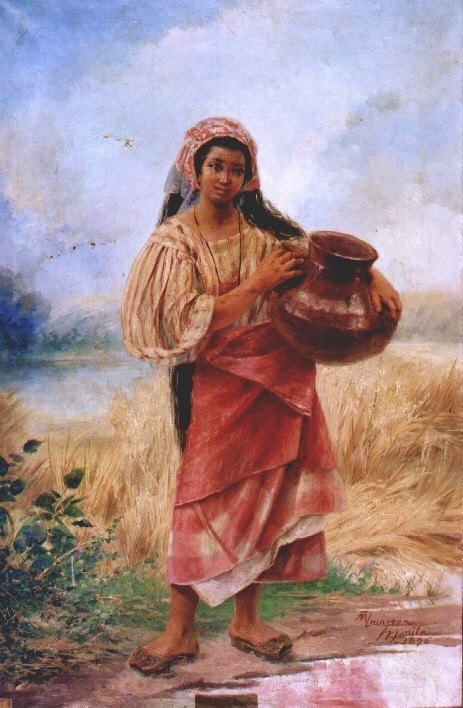

But during Miguel’s long wait for his scholarship, he was able to contribute 6 illustrations of native plants for Volume 1 of Flora de Filipinas (1878) by Fr. Manuel Blanco and at least one for Volume 2. Then a new magazine called La Ilustración del Oriente printed his illustration “La Lechera” (“The Milk Maid”) for its Christmas issue.

After Miguel and Felix bid farewell to the Philippines for their studies, the two were disillusioned by the lack of devotion of their classmates in Madrid. But eventually, they were able to make it work, and they spent their last academic year in Rome.

After 12 years in Europe, Miguel Zaragoza returned to the Philippines in 1891. His brother José, who was then a successful businessman and civic leader, came up with an offer he couldn’t refuse — revive the short-lived La Ilustración Filipina magazine (1859-60). José would be involved with writing for the magazine, while Miguel would also write and obviously contribute artwork for the publication. The first issue of Ilustracíon came out on 7 Nov 1891. The weekly publication became successful as it attracted the growing ilustrado class despite being derided by Spanish writer Wenceslao Retana. He drew portaits of indios, working-class mestizos, and the principalia (ruling nobility). He would then write the figures’ biographies.

Eventually, he would branch out into poetry, short stories, polemics, art and music criticism and history. His favorite subject to write about however, was his friend Juan Luna.

Photo from UST Miguel de Benavides Library

Photo courtesy of Rafael Minuesa

Aside from the pen and the brush, he would also contribute by teaching young painters. He taught at his alma maters — the Ateneo, and what became the Escuela Superior de Dibujo, Pintura y Grabado in 1893.

Then on February 25, 1895, his hardworking brother José suddenly died from cerebral hemorrhage, which also spelled the demise of La Ilustracíon. José was the husband of Rosa Roxas, a relative of the first registered architect in the Philippines Felix Rojas (1823-1889) who designed the original Santo Domingo Church.

After that of course came the Philippine Revolution in 1896. Although previously apolitical, he ultimately not only aligned himself with the Filipinos, he was one of only two artist members of the Malolos Congress. On June 12, 1898, Philippine Independence from Spain was declared in Cavite El Viejo whose signatures included that of Miguel Zaragoza.

He would continue to teach at the Ateneo as well as another school, Liceo de Manila during the difficult transition towards American rule. But surprisingly, the Americans were more appreciative of his art and at the St. Louis Exposition of 1904, he won his first gold medal.

When the UP School of Fine Arts was founded on June 18, 1909, he became one of its first three professors.

Photo from the Museo de Bellas Artes de Córdoba.

The Zaragoza brothers’ creative legacy would be continued by Carmen Zaragoza y Rojas, José’s daughter. She took formal painting lessons, and she also helped her father José publish La Ilustracion Filipina. Then in 1892, she was awarded for her painting “Dos Inteligencias” during the anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America. She would then win a copper medal for her two landscapes exhibited in the 1895 Exposición Regional de Filipinas.

In 1896, she married nationalist and businessman Gregorio S. Araneta and they had 14 children.

Elias Zaragoza y Roxas, her brother, would become the first licensed Filipino electrical and chemical engineer to practice in the country. His son, José Ma. Zaragoza y Vélez, became an architect.

José Ma. Zaragoza was the architect behind the current Santo Domingo Church, the Meralco Building, St. John Bosco Church, National Shrine of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal, Virra Mall in Greenhills, Casino Español de Manila and the expansion of the Quiapo Church among others. His modern “Spanish style” unique to the Philippines has inspired residential design in the country during the 1950s and 1960s.

José’s son, Ramon Ma. Zaragoza would also follow in his father’s footsteps as an architect, but specializing in heritage restoration. He was involved in the restoration of Intramuros, Vigan and some antique churches. Although he departed this world on July 4, 2019, why should his legacy die with him? Restoring the greatness of a country has never been one person’s task. The more people who support that goal (especially with funds), the closer we get to its realization.

References:

- Zaragoza, Ramón Ma. “Zaragoza Family of Quiapo”. Budhi, Vol. 10 No. 2 (2006), pp 98-119

- Santiago, Luciano P. R. “Miguel Zaragoza, The Ageless Master (1847-1923)”. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, Vol. 14, No. 4 (December 1986), pp. 285-312

- La Ilustración Filipina, via Wikipedia. Retrieved 11 April 2021

- The Asian Cultural Council Philippines Art Auction 2016

- Carmen Zaragoza y Rojas, via Wikipedia. Retrieved 11 April 2021

- José María Zaragoza, via Wikipedia. Retrieved 11 April 2021

- The legacy of architect Ramon Zaragoza in the heritage sites he helped bring back to life

Article by Ken Tatlonghari.

Cover art by Diego Torres.

Renacimiento Manila

All rights reserved.

The Renacimiento Movement. What, then, is the Renacimiento Movement? The movement is the core philosophy of the organization. It is founded on the reality that heritage is a cornerstone of holistic development and that it is indispensable in ensuring quality of life. As such, cultural revival is necessary for the promotion of heritage in the national agenda. Heritage should be driven by the people, regardless of race, gender, creed, or religion. This cultural revival can be achieved through the following ways: government support, the advancement of private initiatives, and the engagement of the people.

Leave a comment