Foreword

Words by: Diego Gabriel Torres

Kabihisnan: History Through Fashion

The title of the exhibit, Kabihisnan, is a play on the Filipino word kabihasnan meaning civilization and bihis, referring to clothes and fashion. The exhibit aims for visitors to see and experience Philippine history utilizing recreated articles of clothing from a specific time period in Manila’s history.

This is in line with Renacimiento Manila’s advocacy of promoting Manila’s history and culture. This includes using living history or reenactments which utilize recreated attires. The exhibit was first held in 2023 in Intramuros, showcasing primarily recreated military uniforms.

This year’s Kabihisnan Exhibit will showcase recreated civilian attire and uniforms from the late Spanish period of the years 1840 to 1899. This was a period immortalized in the novels of Dr. Jose Rizal as well as preserved through the watercolor paintings of painters such as Jose Honorato Lozano and Justinian Asuncion. The 19th century or the late Spanish period was a time of great transformation for the colony and would culminate in the struggle for Philippine independence.

This exhibit is done in partnership with Historia Viviente Manila, a cultural living history organization, and the Intramuros Administration.

The Late Spanish Period in the Philippines

Words by: Ivan Beley

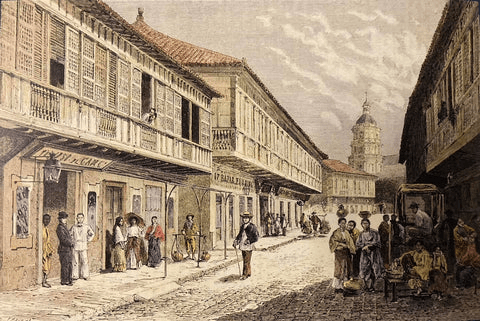

The 19th century was critical to the Spanish Colonial Philippines because they were affected by changes in the Iberian Peninsula. Concepts of the French Revolution and technological advancements of the Industrial Revolution produced a lasting impact in Spain and the colonies. These occurrences had profound effects on the socio-political and economic scene of the Philippines.

The social order in the Spanish Colonial Period significantly changed during this period. The native elite group known as the Principalias became powerful as land owners, municipal officials, and intermediaries between the colonial state and the Filipino masses. Simultaneously, a new educated class called the Ilustrados, influenced by liberal ideas from their education in Europe, began advocating for reforms. Meanwhile, the Mestizo class expanded through the wealth of the Chinese residing in the Philippines, resulting in a new group called the Mestizo de Sangleys, who were able to climb the social ladder through their wealth from trade and farming, joining the Principalias and the Ilustrados. Even with these internal changes, the overall colonial structure was still in place, with the Peninsulares, the Spaniards born in Spain, and the Insulares (Criollos), Spaniards born in the Philippines, placed at the top, followed by the Mestizos and the Principalias in the middle. Local natives, referred to as the Indios, held the lower class, with Chinese inhabitants, the Sangleys, though economically prominent, frequently discriminated against and subject to legal discrimination, holding the lowest place in the hierarchy.

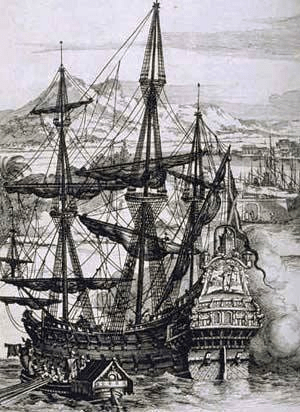

The 19th century also saw major economic transformation. The Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade ended in 1815, causing monopolies in provinces such as Ilocos, Batangas, Laguna, and Negros. The monopolies were dependent upon high taxes and debt peonage, keeping small farmers hostage to dependency. The economic system transformed for the better when Spain opened Philippine ports to global trade in 1834, causing thriving trade and drawing in additional foreigners, particularly after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

Through these economic and social advancements, political organization changed drastically. The Ilustrados started challenging the socio-political condition with the Glorious Revolution of 1868 and the Cadiz Constitution of 1812. They challenged issues such as government abuses of natives and ecclesiastical abuses, which ultimately gave rise to the Cavite Mutiny in 1872, challenging the legitimacy of Spanish colonial rule and setting the stage for the Propaganda Movement and the Philippine Revolution of 1896.

Timeline of Events in Manila During the 19th Century

Words by Diego Gabriel Torres and Ivan Beley

1805: The Balmis Expedition brought the smallpox vaccine to Manila from Spain and Mexico.

1808: Napoleon Bonaparte invades the Iberian Peninsula; The Mexican War of Independence begins.

1812: The Cadiz Constitution was proclaimed which promised citizenship to Spanish subjects (except salves) and representation in the Cortes. The constitution was scrapped two years later by King Ferdinand VII.

1808-1833: The Spanish American Wars of Independence would lead to the end of Spanish dominion in the Americas.

1815: The Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade comes to an end.

1823: Capitan Andres Novales, a criollo, leads an uprising of disgruntled American (Spanish America) and native troops in Manila, proclaiming himself emperor. The revolt is crushed after a day, and Novales is executed.

1834: The Ports of Manila are opened to international trade. Liberals burned convents and churches in Spain, and they confiscated Church Properties.

1843: Native troops of the Tayabas Regiment launch a revolt and capture Fort Santiago, the only native force to capture the fort. The uprising is crushed after a day.

1863: A strong earthquake destroyed many of Manila’s landmarks.

1868: The Guardia Civil is established.

1869: The opening of the Suez Canal; members of a Comité de Reformadores (Committee of Reformists), together with members of the Principalia class from Manila-Area Pueblos, serenaded Liberal Governor General Carlos Maria de la Torre; the establishment of the Juventud Escolar Liberal led to the arrest of student activists, including Felipe Buencamino.

1872: The Cavite Mutiny; Leading liberals and reformists are imprisoned and exiled; three priests associated with the secularization movement, Fr. Jose Burgos, Fr. Mariano Gomes, and Fr. Jacinto Zamora, are implicated and executed.

1880: A Major earthquake damages many buildings in Manila.

1887: A group of young Filipinos called the Illustrados, like Jose Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, and Graciano Lopez Jaena, who were studying in Spain called the attention of the Spanish government through writing in a Liberal Periodical called La Solidaridad.

1896: The Philippine Revolution begins; battles rage across Luzon and just outside of Manila; Revolutionaries score several victories in Cavite; Dr. Jose Rizal is executed.

1897: Spanish reinforcements arrive in Manila; General Lachambre’s Cavite Offensive destroys the rebel stronghold of Cavite; Pact of Biak na Bato brings an uneasy peace between the revolutionaries and the Spanish.

1898: The Spanish-American War begins; Philippine revolutionaries resume the struggle and sweep Spanish forces across the islands; Philippine Independence is declared; Manila falls to US Forces; Spanish rule ends in the country after 333 years. The Treaty of Paris was signed

1899: The First Philippine Republic is established; the Filipino-American War begins. The establishment of the First Philippine Commission.

SOURCES:

- Dumol, Paul A., and Clement C. Camposano. 2018. The Nation as Project. Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines: Vibal Group Inc.

- Guerrero, León Ma. 2007. The First Filipino: A Biography of José Rizal.

- De La Costa, Horacio. 1992. Readings in Philippine History: Selected Historical Texts Presented with a Commentary.

- Tan, Samuel K. 2008. A History of the Philippines. UP Press.

- Francia, Luis H. 2013. History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos. Abrams.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. 1990. History of the Filipino People. 8th ed. Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines: R.P. Garcia Publishing Co.

- Schumacher, John N., S.J. 1991. The Making of a Nation: Essays on Ninteenth~Century Filipino Nationalism. Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines: Ateneo De Manila University Press.

The Church and the Colony

Words by: Diego Gabriel Torres

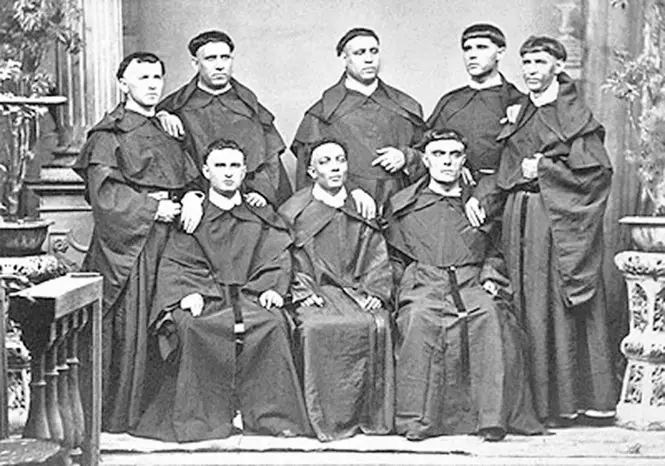

The Catholic Church formed one of the pillars of Spanish colonial rule in the country, next to the state and the military. Under three centuries of Spanish rule, the Church would come to dominate the lives of the inhabitants of the islands.

Religious orders helped spread the faith as missionaries and maintained parishes in evangelized areas. Each religious order wore a particular habit, reflecting the specific teachings of their order.

Augustinian Friar’s Habit

Words by: Ivan Beley

The Augustinian Friars in the Philippines during the 19th century continued to be a prominent representation of religious dedication, even in the tropical climate of the region. Grounded in the medieval heritage of St. Augustine’s community, their clothing included a basic wool tunic (the soutane), a scapular worn on the front and back, and a black leather belt (cincture) secured around the waist. Over the years, friars engaged in Philippine missions adapted the heavy European wool to a lighter, natural cotton blend, which was produced locally in convent workshops. This adaptation offered improved breathability while reducing weight, making it more suitable for the heat and humidity found in Luzon and the Visayas.

The various elements of the habit held deep symbolic significance. The black wool or cotton tunic symbolized penance and poverty, while the scapular, comprising two pieces of cloth hanging at the front and back, stood for commitment to Mary. The black belt signifies all deaths of the animal inclinations, even those parts that include the sources of lust, which was traditionally provided by the Blessed Virgin Mary to Saint Monica as a symbol of protection towards the order.

In addition to these essential items, friars frequently carried a wooden rosary and opted for simple leather or woven abacá sandals (higantes) rather than the closed shoes typical in Europe. During outdoor processions or visits to fields, some friars added a wide-brimmed straw hat and a light linen cloak to their attire.

By the mid-19th century, the Augustinian Provinces in Manila and Cebu had established specific standards for certain items, such as the scapular’s dimensions and the cincture’s width, while permitting flexibility in material selection based on available local resources. In the later years of Spanish governance, photographs captured friars in both fully white habits (crafted from bleached cotton) and traditional undyed gray habits, indicating the varying availability of bleaching agents or dyeing facilities across different convents. Nevertheless, the recognizable shape of the Augustinian habit—marked by its hooded tunic and simple cincture—remained uniform throughout the archipelago.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

This display showcases an Augustinian Friar’s Habit during the 1800s, characterized by an ankle-length soutane or tunica made of undyed cotton twill, complemented by an attached hood (cuculla) that embodies the order’s principles of simplicity and humility. The outfit features a scapular, consisting of two rectangular cotton panels joined at the shoulders as a symbol of the friar’s devotion, along with a six-foot cincture—a black leather belt tied, securing the habit at the waist. Accompanying the ensemble are modest sandals made with woven abacá straps and split-toe leather soles well-suited for the tropical climate of the Philippines. Additionally, for outdoor ministry, the friar would don a wide-brimmed straw hat (sombrero de heno) to shield against the sun while upholding the austere dignity tied to the Augustinian mission.

SOURCES:

- LeRoy, James A. “The Friars in the Philippines.” Political Science Quarterly 18, no. 4 (1903): 657–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/2140780.

- Pilapil, Vicente R. “Nineteenth-Century Philippines and the Friar-Problem.” The Americas 18, no. 2 (1961): 127–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/979040.

- Gerencia. 2018. “LAS ÓRDENES RELIGIOSAS EN FILIPINAS.” Sociedad Geográfica Española. December 20, 2018. https://sge.org/publicaciones/numero-de-boletin/boletin-61/las-ordenes-religiosas-en-filipinas/.

- Borre, Ericson, OSA. 2021. “The First Hundred Years of the Augustinians in the Philippines (1565 -1665).” Daily Life, Customs, and Traditions 56 (167). https://doi.org/10.55997/1001pslvi167a1.

- Augustinian Province of the Most Holy Name of Jesus of the Philippines. THE AUGUSTINIAN HABIT The garment worn by the Augustinian friars is called a habit….Facebook. May 10, 2025. https://www.facebook.com/OSApilipinas/posts/the-augustinian-habitthe-garment-worn-by-the-augustinian-friars-is-called-a-habi/1136693243426889/

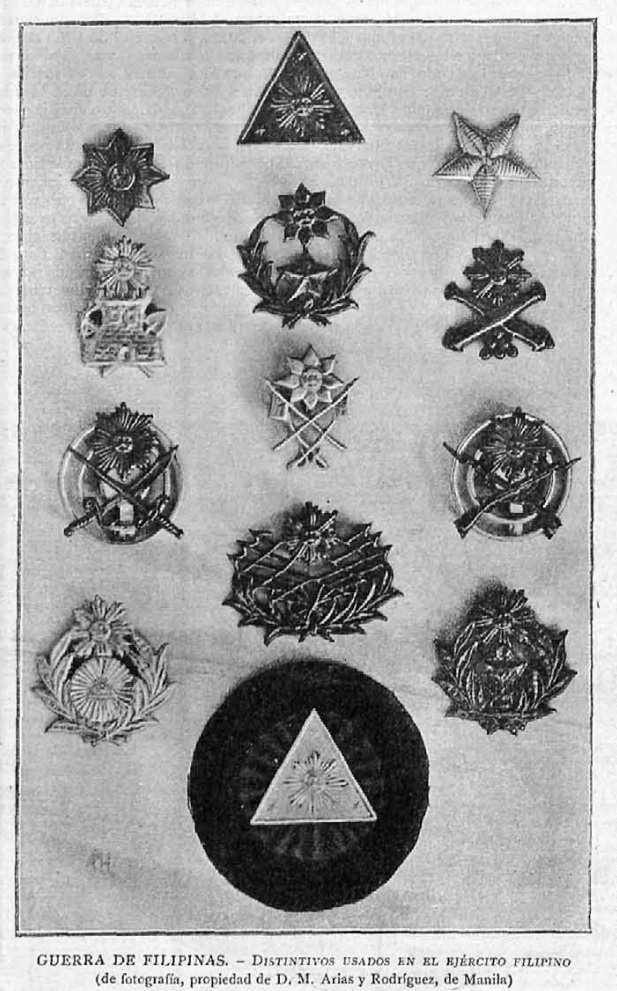

Ejército de Filipinas (Spain’s Army of the Philippines)

Words by: Diego Magallona

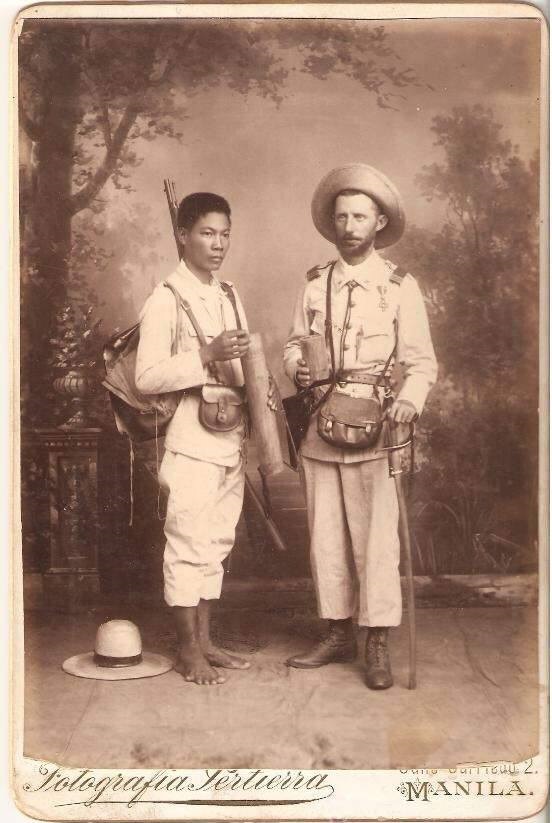

Spain’s Ejército de Filipinas (Army of the Philippines) traced its origins to 1587, when King Philip II of Spain ordered Manila to be garrisoned by 400 soldiers recruited from the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico). For much of the first 200 years of Spanish rule in the Philippines, the permanent garrison of the Philippines was a relatively small force of soldiers from Peninsular Spain and New Spain, while native Filipino warriors rarely served in a regular capacity but more often as auxiliary or militia forces called upon to fight when needed. This began to change in the 1800s when the Army of the Philippines began forming regular army regiments recruited from the native Filipinos, armed, trained, and dressed in a similar fashion to European armies of the period. The Filipinos in these units served as privates and non-commissioned officers, commanded by Spanish officers.

(Acción Cultural Española (ed.). 2006.)

By the 1890s, Filipinos made up the bulk of the Spanish Army’s strength in the Philippines, with natives serving in the Infantry, Cavalry, Engineers/Sappers, Guardia Civil (militarized police force), Carabineros (port/customs guards and coast guard), and other Army Corps. Only the Artillery Regiment garrisoned at Fort Santiago recruited exclusively from Peninsular Spaniards. The Captain-General’s bodyguard unit, the Alabarderos (Halberdiers), was drawn from the best men of this Artillery Regiment. At the beginning of 1896, the onset of the Philippine Revolution, the strength of the Army of the Philippines was reported as 13,291 men – “4,269 son europeos y 9,022 indigenas” – Filipino soldiers numbering more than double the number of Spanish officers and men. Despite this, only Spaniards could serve as commissioned officers; the highest rank a native (without Spanish blood) could hold was Sargento Primero (1st Sergeant).

During the Philippine Revolution, the Army of the Philippines, reinforced by fifteen battalions of Cazadores – light infantry – and other units from Peninsular Spain, fought the revolution to a stalemate resulting in the Pact of Biak-na-Bato and the exile of many revolutionary leaders in 1897. In 1898, the United States went to war with Spain and destroyed the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay. The exiled leaders of the Revolution, led by Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, returned with arms and ammunition urging the country to rise up and resume the revolution against Spain. The Army of the Philippines began to disintegrate as its garrisons across the archipelago were besieged, and many of their once-loyal Filipino soldiers began deserting, defecting, and mutineering in the face of certain defeat. Spain lost control of much of the country and eventually the entire archipelago, and what remained of the Army of the Philippines surrendered to the US Army after the Mock Battle of Manila on 13 August 1898.

SOURCES:

- España, Ejercito de Filipinas. Ejército de Filipinas: Estado Militar de todas las armas é institutos y escalafón general en 1.° de enero de 1889. Manila: Establecimiento Tipográfico de Ramirez y Compañía, 1889.

- Ministerio de la Guerra. Anuario Militar de España, Año 1896. Madrid: Depósito de la Guerra, 1896.

- Toral, Juan. El Sitio de Manila (1898): Memorias de un voluntario. Manila: Imprenta Litografica Partier, 1898.

Native Soldier’s Campaign Uniform, 70th “Magallanes” Infantry Regiment, Army of the Philippines (Spain), 1890s

Words by: Diego Magallona

Native Filipinos (called Indigenas or Indios by the Spanish) formed the bulk of the infantry in Spain’s Ejército de Filipinas (Army of the Philippines), serving as enlisted soldiers and non-commissioned officers. At the outbreak of the Philippine Revolution in 1896, there were seven regiments of native infantry in the Ejército de Filipinas.

The Regimiento de Infantería “Magallanes” num. 70 spent most of the Philippine Revolution garrisoned around Manila to defend the city. The regiment is most notable for providing the firing squad that executed Filipino national hero Dr. Jose Rizal on 30 December 1896 at Bagumbayan, Manila. On 13 August 1898, with the city under siege by Filipino and US forces, the Spanish and US armies staged a “Mock Battle” before the Spanish surrendered Manila to the Americans. The 70th Infantry were among the Spanish forces that surrendered on that day. With the Philippines lost to Spain, the Ejército de Filipinas was soon disbanded, marking the end of the 70th Infantry Regiment.

These soldiers were most often seen wearing the guerrera de rayadillo uniform. Rayadillo is a cotton fabric of small blue and white stripes adopted by the Spanish Army for their tropical uniforms from c. late 1860s to the 1910s. Guerrera refers to the specific cut of the uniform, introduced in 1887 and in service with the Spanish Army until 1898. Guerrera tunics of the Ejército de Filipinas have their front buttons hidden, and sometimes a standing collar, distinguishing them from Guerrera uniforms of the Spanish Armies of Cuba and Puerto Rico.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

Displayed is the traje de campaña (campaign/battle dress) of a native Filipino soldier in the Spanish Army’s 70th Infantry Regiment: a Guerrera pattern military tunic and pantalones (trousers) both made of rayadillo fabric. Worn over the uniform is a set of leather equipment including a belt, suspenders, bayonet frog, and three leather pouches to store ammunition for the Model 1871 Remington Rolling Block rifle. The straw sombrero used as a campaign hat has an oilcloth band with the regiment number painted on it. The soldier wears no footwear, as most Filipino soldiers of the period preferred to march and fight barefoot.

SOURCES:

- Combs, Bill. “Guerrera: The Rayadillo Tunic 1887-1898.” Last modified 2011. http://www.agmohio.com/LRguerrera.htm

- Ministerio de la Guerra. Anuario Militar de España, Año 1896. Madrid: Depósito de la Guerra, 1896.

- Toral, Juan. El Sitio de Manila (1898): Memorias de un voluntario. Manila: Imprenta Litografica Partier, 1898.

Native Soldier’s Full Dress Uniform, Army of the Philippines (Spain), 1870s

Words by Diego Magallona

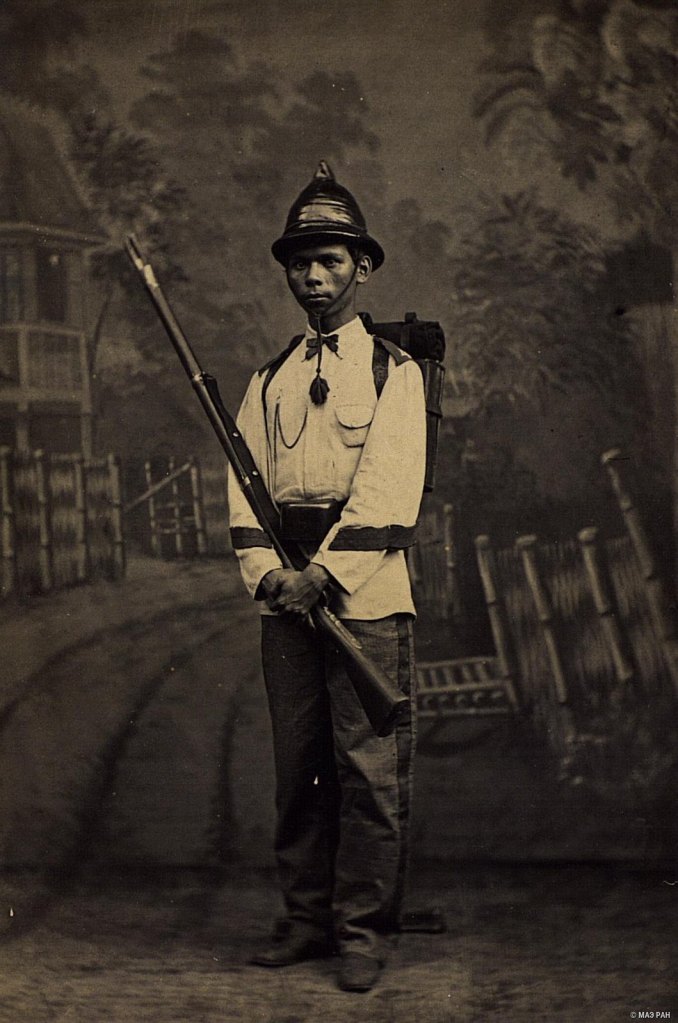

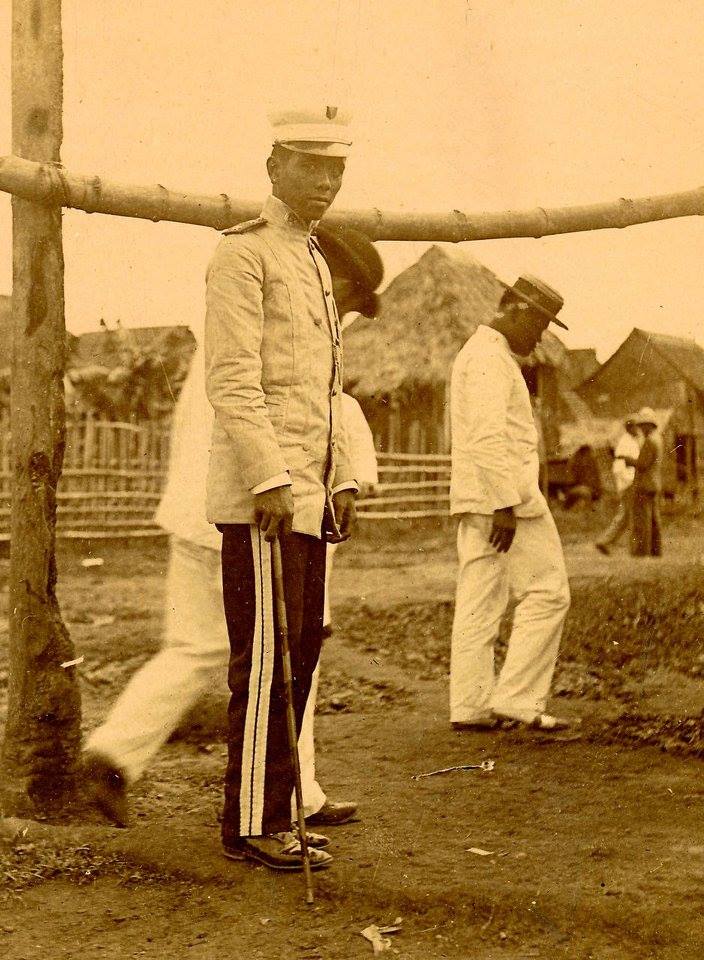

Throughout the 19th century, the Ejercito de Filipinas (Spanish Army of the Philippines) underwent many significant changes as warfare during this period was advancing rapidly. In addition to the introduction of new weapons, technology, and tactics, nearly every decade of the 19th century saw different uniforms being worn by the soldiers of the Army. Until the 1860s, these changes would mostly be observed in illustrations or paintings. But from the 1870s onwards, the growing accessibility and popularity of photography allowed for more soldiers to be photographed with their actual uniforms and equipment.

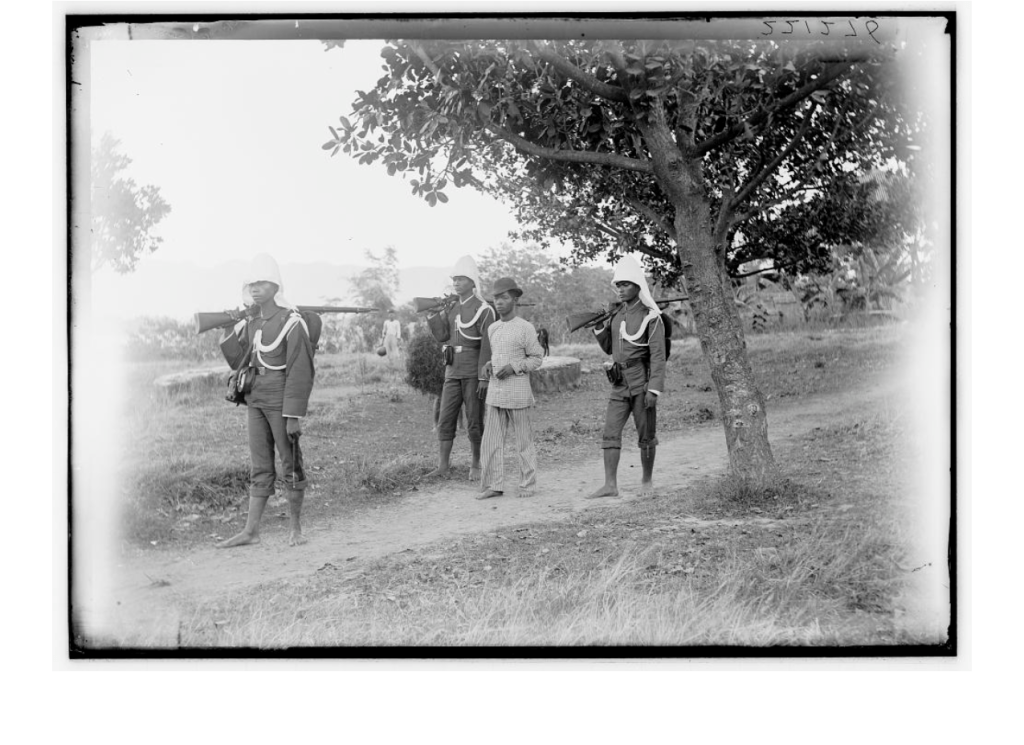

One of the changes to military life brought about during the 19th century was the development of separate attires for different tasks or occasions. The photographs featured come from the 1870s and feature native Filipino soldiers in traje de gala (full dress) and traje de diario (service) uniforms during the 1870s. The de gala or full dress uniform was worn on formal occasions such as parades, ceremonies, and certain religious festivals. Gala uniforms typically featured the white Blusa military tunic. The de diario or service uniform was used for most of the soldiers’ everyday functions, with a Blusa made of rayadillo fabric. Soldiers also had separate uniforms for campaigns or pitched battles, manual labor, quarters/barracks, etc.

The 1870s also saw the widespread adoption of military sun helmets adopted by several militaries from the mid-19th century as part of their tropical uniforms. In English, these are often referred to as “pith helmets” as the British and some other nations made their sun helmets out of pith or cork. The Spanish Army, however, manufactured most of their sun helmets from wool. The Spanish term for their sun helmet was capacete (Spanish for helmet) and from the 1870s it began to replace the salacot or salakot – a traditional Filipino wide-brimmed hat which Spanish and Filipino soldiers in the Ejercito de Filipinas had adopted for use during campaigns since at least the 1840s (although traditional salakot seem to have remained in use by the Spanish Army in Mindanao up to the 1890s).

EXHIBIT ITEM:

This is a replica of a de gala uniform worn by a Native Filipino infantryman in the Spanish Army during the 1870s. It consists of a blusa and pantalones made of paño blanco (white cloth, most likely cotton) with maroon trimmings and stripes. The single maroon stripe on each outer pant leg identifies the soldier as part of the Infantry. He also wears an 1870s Spanish-style capacete (sun helmet), also covered in white cloth. When under arms, he would wear a belt around his waist with a single ammunition pouch for his rifle or musket. When in de gala uniform, Filipino soldiers were required to wear boots.

SOURCES:

- Acción Cultural Española (ed.). El Imaginario Colonial: Fotografia en Filipinas durante el periodo español. Madrid: Casa Asia, 2006.

- España, Ejercito de Filipinas. Ejército de Filipinas: Estado Militar de todas las armas é institutos y escalafón general en 1.° de enero de 1889. Manila: Establecimiento Tipográfico de Ramirez y Compañía, 1889.

Guardia Civil (Provincial) Service Uniform, 1890s

Words by: Arthur Napiere

The Guardia Civil in the Philippines was established under the approval of the Royal Order of March 24, 1868. Its primary duty was to ensure peace and order in the Philippine provinces (e.g. Nueva Ecija, Bulacan, Cavite, Ilocos etc.). Manila and Mindanao specifically were outside the GC’s jurisdiction. The first regiments or Tercios of the Guardia Civil in the Philippines were formed from native infantry regiments of the Ejercito de Filipinas (Spanish Army of the Philippines) units that were disbanded and reorganized into Guardia Civil units.

The Guardia Civil remained under the command of the Ejercito de Filipinas, and thus functioned as a gendarmerie or a military police force with law enforcement duties over the civilian population (as opposed to “Military Police” who are charged with law enforcement of military personnel / within military grounds). As with the rest of the Spanish Army, native Filipino soldiers of the Guardia Civil could only hold enlisted and non-commissioned officer ranks, and were led by Spanish military officers.

Though seen as a more effective replacement to previous police and law enforcement units, and sometimes had good relations with the communities they were assigned to, the Guardia Civil gradually earned a reputation among many Filipinos as an intrusive, abusive, and brutal instrument of Spanish colonial rule.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

For the Guardia Civil’s traje de diario (service dress), they wore a type of uniform called blusa de guingón, made of guingón fabric with two pockets on the left side of the chest and another on the lower right, along with a fallen collar within the jacket. They also wore the pantalon de guingón, with the same fabric as the jacket and featured a maroon stripe on both sides of the pants. They also had accouterments known as hombreras (epaulettes) on both shoulders and a forrajera, a braid that ran from the shoulder to the middle of the chest. On Sundays and parades, the Guardia Civil were required to wear maroon collar and cuffs. Their headgear was a white sun helmet of what is called capacete. Guardia Civil soldiers in the provinces could be seen both barefoot or wearing boots.

SOURCES:

- Marco, Sophia Martha B. “The Guardia Civil in the Philippines 1868-1898: Filipino Soldiers in Service of the Colonial State”. (Diliman, Quezon City, 2019).

- Peréz, M. Cartilla de uniformidad para el ejército de Filipinas/Redactadas por una Junta de Jefes y mandada observar por el Excmo. Sr. Capitán General. Manila, Philippines. (1887)

Guardia Civil Veterana (Manila) Service Uniform, 1890s

Words by: Alex Avila

The Cavite Mutiny of 1872 exposed inadequacies in the capabilities of the recently formed Guardia Civil in the Philippines. In response, Governor General Rafael Izquierdo y Gutierrez established an additional force of police to enforce law and order in the very heart of Manila. This was the Guardia Civil Veterana (GCV), an elite gendarmerie police force that patrolled the walled city of Intramuros as well as the districts of Santa Cruz, Sampaloc, Tondo, San Lazaro, Binondo, and Malate.

The Guardia Civil Veterana included both Spaniards and Filipinos. Filipinos served as Privates and Non-Commissioned Officers under the leadership of Spanish officers and NCOs. As implied by their name, men of the Guardia Civil Veterana were recruited exclusively from veteran troops of the Ejercito de Filipinas, especially Filipino soldiers with previous service in the Infantry, Guardia Civil, or other Army Corps.

During the Philippine Revolution of 1896, the Guardia Civil Veterana were responsible for hunting down, arresting, and eliminating suspected and identified members of the Katipunan in Manila. They were feared for their swift and brutal action against threats to the Spanish colonial regime. During the later phase of the Philippine Revolution, however, some of its members defected to the Revolutionary Army and helped them take parts of Manila close to Intramuros.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

This item represents the traje de diario or daytime service dress of a Native Filipino soldier in the Guardia Civil Veterana during the 1890s. The main uniform consists of a guerrera de guingon – a guerrera pattern military tunic of dark blue guingon fabric, pantalon de guingon trousers of the same material with a single maroon stripe on each outer pant leg. They wear white hombreras and forrajera similar to the Guardia Civil, but unlike their provincial counterparts, the Guardia Civil Veterana always wear the maroon collar and cuffs on their uniforms. Under the guerrera tunic, GCV soldiers wear a collared long-sleeved shirt with a black necktie. The headgear is a white capacete sun helmet. When in service dress, they are usually required to wear boots.

SOURCES:

- Marco, Sophia Martha B. “The Guardia Civil in the Philippines 1868-1898: Filipino Soldiers in Service of the Colonial State”. (Diliman, Quezon City, 2019).

- Corpuz, O.D. Saga and Triumph: The Filipino Revolution Against Spain.

What the Indios or Naturales Wore Attires of the Native Masses (1840s)

Male Naturales Laborer’s Attire

Words by: Ivan Beley

The Boxer Codex underscores the significance of clothing and adornments in expressing social status among Filipinos during the Spanish Colonial Period, beginning from the 16th century. Commoners, referred to as Male Naturales or Indios, typically wore minimal garments and jewelry, in stark contrast to the elite class known as the Principalias.

By the 18th century, men’s fashion transformed, moving away from traditional loincloths to more structured clothing such as the baro and salaual. These were made from coarse guinara cloth and paired with knee-length trousers. The potong, a headpiece introduced in the 16th century, became a symbol of bravery, especially in battle.

As the 19th century approached, the design of the potong shifted to a more practical style, gaining popularity among the working class. Men’s baros featured V-necks and long sleeves, while trousers became increasingly narrow. Common dyes, such as indigo and achuete, were widely used, and during the rainy season, laborers often donned palm-made anajao raincoats. Carriage drivers, or cocheros, sported uniforms that mirrored the status of their affluent employers, often opting for all-white outfits for practicality.

The Male Naturales began to adopt Western-style attire, with all-white ensembles symbolizing professional status. Workers tended to wear practical clothing appropriate to their jobs; for instance, farmers opted for simpler garments, while domestic workers frequently received clothing from their employers. During community fiestas, it was common for lower-class individuals to be gifted clothing, reinforcing cycles of dependence rooted in patron-client relationships.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

The typical outfit of a lowland Male Naturales Laborer in the 1840s was that which was meant to be practical and comfortable in the heat of the tropical climate. As seen in this display, he would typically have on a Camisa de Chino, a collarless Camisa made of rough cotton or canton cloth, usually worn untucked for convenience. These were accompanied by Salawal or Calzones, drawstring trousers from knee to ankle, typically in solid or checkered patterns and made of durable material such as abacá or cotton. He also brought with him a Tapis, a woven fabric worn as a sling for tools or wiped against to remove perspiration while working. For sun protection, a Salakot Hat fashioned from rattan or bamboo was a must. Most workers were barefoot, but some wore Bakya (wood clogs) or abacá sandals. Hair was often cut short or tied in a topknot (buhok sa isang tabi) in the countryside, both practical and a matter of cultural pride.

SOURCES:

- Coo, Stephanie Marie R. 2019. Clothing the Colony: Nineteenth-Century Philippine Sartorial Culture, 1820-1896. Ateneo De Manila University Press.

- Camagay, Maria Luisa T. 2018. Unraveling the Past: Readings in Philippine History.

- De La Costa, Horacio. 1992. Readings in Philippine History: Selected Historical Texts Presented with a Commentary.

Female Naturales Laborer’s Attire

Words by: Ivan Beley

Working-class Natives, known as the Naturales, especially the females, often wore practical and simple clothing due to economic hardships. This straightforward style made them less vulnerable to foreign fashion influences. Their garments, like the baro and saya, were made from affordable materials such as cotton, guinara, and sinamay, with little decoration. The lack of luxurious details, like lace or intricate embroidery, ensured that their outfits remained functional and modest, even while reflecting elite styles in their overall design.

As the 19th century progressed, the clothing of Female Naturales began to change, incorporating more elegant features such as angel sleeves and vibrant colors. Some women adopted styles influenced by the elite, including petticoated skirts, particularly for formal or staged photographs. However, these images were often embellished or specifically designed for studio portraits and public displays. A significant instance is the 1887 Madrid Exposition, where weavers and cigar workers wore idealized traditional clothing to appeal to foreign spectators.

In everyday life, Female Naturales usually wear simpler, more practical outfits. For example, factory workers known as cigarreras often wore worn versions of the baro’t saya. They may have dressed more elaborately for special events or photographs. Despite enduring low wages and economic challenges, the textile industry in factories flourished, often under exploitative circumstances, such as charging workers inflated prices for fabric on installment plans.

Images of working women often romanticized their looks, presenting them as neat, graceful, and well-dressed, a sharp contrast to the reality of their working environments. Weavers (tejedoras) and cigar workers were frequently showcased for their visual appeal rather than offering an honest depiction of their labor, thereby reinforcing colonial stereotypes and aesthetic norms.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

This example shown in the display is an outfit of a Female Naturales in the 1840s. She wore a loose-fitting Baro, a hip-length blouse with short or elbow-length sleeves, made from breathable fabrics like plain cotton, abacá, or sinamay in white or undyed colors to ensure comfort during lengthy manual labor. Accompanying this blouse, they donned a Patadyong or Saya—either a wrap-around or tubular skirt often decorated with stripes or checkered patterns, fashioned from locally sourced fibers such as abacá or cotton. To maintain practicality and modesty, women would sometimes layer a tapis over their skirts, serving both as an apron and an overskirt. Footwear was usually minimal, with many women working barefoot or opting for wooden clogs, known as Bakya, or Abacá Slippers for market trips. Hairstyles were commonly simple, featuring a bun or a single braid secured with a ribbon or string, while headscarves or bandanas offered protection from the tropical sun. Functional accessories, such as hand-woven baskets or bilao, were generally utilized to carry commodities, either being hand-held or balanced upon the head.

SOURCES:

- Coo, Stephanie Marie R. 2019. Clothing the Colony: Nineteenth-Century Philippine Sartorial Culture, 1820-1896. Ateneo De Manila University Press.

- Camagay, Maria Luisa T. 2018. Unraveling the Past: Readings in Philippine History.

- De La Costa, Horacio. 1992. Readings in Philippine History: Selected Historical Texts Presented with a Commentary.

The Sangleys: Chinese Fashion in Manila During the 19th Century

Words by: Diego Gabriel Torres

The Chinese, referred to as Sangleys, were an important part of Manila’s economic and cultural life since pre colonial times and continued to be as important during the 19th century. They worked as laborers and as skilled artisans, and those who have success were able to establish themselves as merchants and businessmen.

Sangley Merchant Attire 1840s

Words by: Ivan Beley

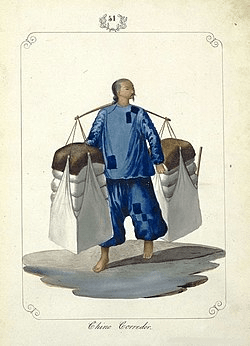

During the 19th century, the Chinese immigrants, often referred to as the Sangleys, held tightly to their native customs, dress, and traditions, which led the Spanish colonial authorities to view them as outsiders. Their unique appearance, lifestyles, and business practices clearly distinguished them from the rest of the population. The Sangleys were easily identifiable by their traditional attire, including bisia shirts, loose jareta trousers, thick-soled Manchu shoes, and small caps featuring red knots. A significant amount of their garments, foods, and merchandise were imported directly from China.

A defining aspect of the Chinese during this period was the “queue” hairstyle, a long braid mandated by the Qing dynasty’s Queue Order of 1645. The queue was more than just a cultural marker; it symbolized enforced loyalty to the Manchu rulers, with severe penalties for those who refused to comply. This mandate was part of a larger and violent resistance that persisted until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911.

Sangley clothing in the Philippines adapted more to practical needs and social circumstances than to traditional Chinese class divisions. Their attire, typically crafted from silk or cotton, stood in contrast to that of the native indios, who donned the baro and salaual. Wealthy Sangley Merchants often wore well-tailored outfits, including light-colored silk trousers and shirts in subdued tones. Thicker-soled shoes and rounded cerda caps were also common among the affluent Sangleys.

By the mid-1800s, the Sangleys commonly sported simple yet uniform outfits of various lengths and colors. Despite the modesty of their clothing, their growing economic strength was unmistakable. Observers noted that wealthy Sangleys in Manila appeared well-groomed and content, sharply contrasting with the impoverished migrants from southern China. While clothing played a role in signaling social or economic status, factors such as posture, confidence, and overall demeanor were equally important indicators.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

This is an example of the attire of a Sangley merchant that exemplified a blend of Chinese and colonial Filipino styles, crafted to accommodate both business needs and the tropical climate in Manila’s Parian District during the 1840s. These merchants typically wore a Changshan Or Camisón Chino, a lightweight tunic that fell to mid-calf and featured a Mandarin Collar, designed for easy movement with its side slits. Accompanying this tunic were wide-legged linen or cotton trousers that offered ventilation during extended trading hours. Footwear often included black cloth or leather slippers with soft soles, suitable for both indoor and outdoor activities. Accessories were practical, such as a hand-held folding fan, an abacá pouch for coins, and a broad-brimmed straw hat for sun protection during errands. Hair customs varied, with many adhering to Qing Traditions by sporting long braided queues, while others, particularly those who had assimilated or adopted Christian Customs, might choose shorter hairstyles paired with Western-style hats, reflecting a cultural adaptation in the colonial landscape.

SOURCES:

- Coo, Stephanie Marie R. 2019. Clothing the Colony: Nineteenth-Century Philippine Sartorial Culture, 1820-1896. Ateneo De Manila University Press.

- Camagay, Maria Luisa T. 2018. Unraveling the Past: Readings in Philippine History.

- De La Costa, Horacio. 1992. Readings in Philippine History: Selected Historical Texts Presented with a Commentary.

- Kaisa Para sa Kaunlaran Inc., and Teresita Ang-See. 2005. Tsinoy The Story of the Chinese in Philippine Life. Edited by Teresita Ang-See, Go Bon Juan, Doreen Go Yu, and Yvonne Chua. Manila City, Metro Manila, Philippines: Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran Inc.

- Bahay Tsinoy, The Museum of the Chinese in Philippine Life

Sangley Laborer’s Attire 1840s

Words by: Ivan Beley

During the Spanish Colonial Era, a substantial number of Chinese Immigrants or Sangleys, came to the Philippines, from China. As part of the lowest class in Chinese Society, they experienced economic hardships and poverty during the Manchu Dynasty. These Sangley Laborers practiced different trades and offered useful goods and services, dealing mainly in products like sugar, medicine, wax, tea, herbal medicine, and general merchandising. Though a select few were successful, most of them struggled as poor workers, mostly engaging in humble street jobs such as street food vendors, tailors, shoemakers, bakers, barbers, and housemaids.

One of the most well-known groups among these Sangley Laborers were the panciteros, who hawked pansit and chanchao and became ubiquitous figures in urban and rural landscapes. These Sangley workers could be found carrying baskets of food on poles, establishing makeshift stalls along factory sites and busy streets.

Sangley Laborers wore basic attire, usually going shirtless because of the heat, which helped to reinforce their reputation as cheap service providers. Their customary attire was shirts with knotted buttons and hairstyles such as the queue, symbolizing their cultural background. Paintings and photographs done in this period often showed them with clean-shaven heads, clad in their specific attire.

Visual accounts, such as paintings and photographs, not just recorded their work but also caught glimpses of leisure time, evidencing recreational pursuits like smoking, playing games, and relaxation by rivers or lakes. These images evidence the daily lives and major contributions of the Sangleys to Philippine society.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

The example of a work attire of a Sangley Laborer in the mid-19th-century Philippines, displayed here, exemplified a blend of practicality and cultural influences from both Colonial and Chinese heritage. Typically, he donned a Camisa, a loose cotton shirt with options for short or long sleeves, suitable for the tropical climate. This was complemented by salawal, drawstring trousers crafted from durable canton cloth or woven abacá, ensuring comfort during labor. A tapis, a rectangular strip of cotton or abacá, was often used to carry tools or supplies, either slung over the shoulder or tied around the waist. For sun protection, a salakot, a conical straw hat sometimes lacquered or reinforced with metal, was commonly worn. While many laborers worked barefoot, some opted for basic abacá-soled shoes or rattan sandals known as Bakya. Hair was generally kept short for ease, though some chose to maintain the traditional Qing Queue, a testament to their Chinese Identity amidst colonial influences.

SOURCES:

- Coo, Stephanie Marie R. 2019. Clothing the Colony: Nineteenth-Century Philippine Sartorial Culture, 1820-1896. Ateneo De Manila University Press.

- Camagay, Maria Luisa T. 2018. Unraveling the Past: Readings in Philippine History.

- De La Costa, Horacio. 1992. Readings in Philippine History: Selected Historical Texts Presented with a Commentary.

- Kaisa Para sa Kaunlaran Inc., and Teresita Ang-See. 2005. Tsinoy The Story of the Chinese in Philippine Life. Edited by Teresita Ang-See, Go Bon Juan, Doreen Go Yu, and Yvonne Chua. Manila City, Metro Manila, Philippines: Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran Inc.

- Bahay Tsinoy, The Museum of the Chinese in Philippine Life

The Rich Elite: The Principalias

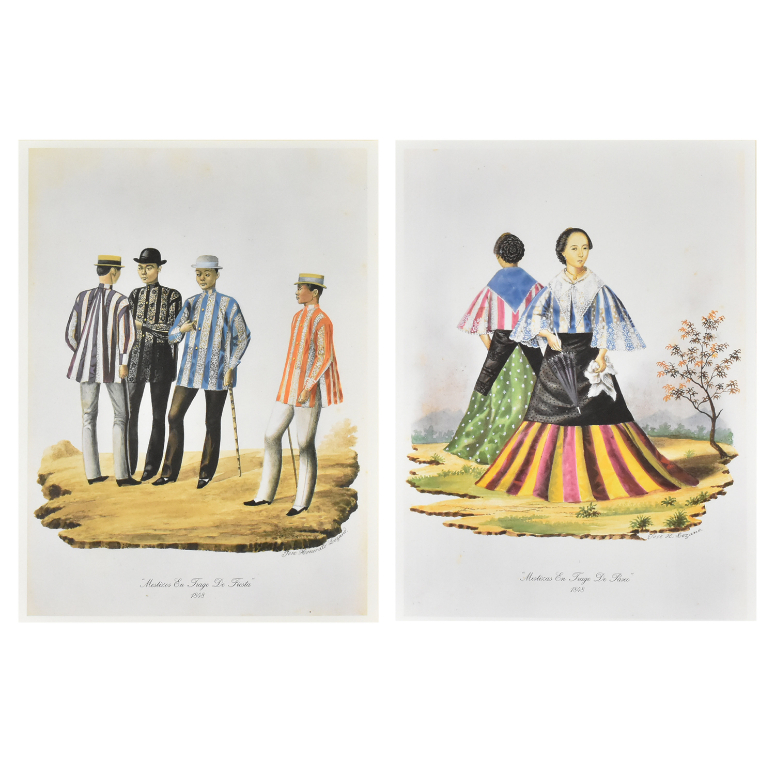

Traje de Mestiza (1840)

Words by: Ivan Beley

During the 18th century, the style of dress for women called the Traja de Mestiza emerged from a culturally rich society shaped by Spanish colonial influence, Anglo-Chinese trade, and the tropical climate. While drawing inspiration from European structures, silhouettes, and styling, this attire also incorporated local fabrics and decorative elements. This is why the Traja de Mestiza is a significant symbol of the Mestiza Identity in the Spanish Colonial Philippines. The women of the Colonial society, including the Indias and the Mestizas, embraced voluminous skirts and layered outfits to reflect the European ideals of status and property.

European influence was evident in tailoring techniques and even fashion accessories. The traditional garments in the native colonies, like the baro, saya, and pañuelo, were reinterpreted through sewing methods taught by the Europeans, while they are still being made from local materials like the piña, which symbolizes luxury. Observers during that era noted that even though native embroidery was intricate and skillful, many designs were still inspired by Spanish patterns.

When the 1840s started kicking in, fashion began to show a blending of styles from social and racial groups. The Indigenous natives and Mestizas often chose between native and European clothing based on the occasion, while the foreign women generally retained their traditional styles. Social standing during the Spanish Period increasingly manifested through the details of attire— the fine textiles, exquisite jewelry, and accessories like embroidered piña kerchiefs and handcrafted hats became prominent markers of class in the Colonial Philippines.

What played a crucial role in defining sophisticated dressing was urbanidad, or genteel conduct. This ideal underscored modesty, elegance, and meticulous detail as advised by European Etiquette Literature. As International trade and influence grew, particularly in bustling urban centers like Manila, Cebu, and Iloilo, local fashion began to globalize. At that time, layered clothing became a symbol of decency and class, as societal expectations dictated that both upper and lower body parts be thoroughly covered, often requiring multiple layers to meet these standards of modesty.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

This outfit is an example of the traditional wear of the Mestiza Women during mid-19th-century colonial Philippine society was characterized by sophistication and cultural synthesis. At the heart of this outfit of the Traje de Mestiza was the floor-length sheer baro, or blouse, made of fine piña or jusi material, usually having elbow-length butterfly or bell sleeves with complex hand-embroidery. This was supplemented by the alampay or pañuelo, a starched triangular shawl that draped elegantly over the shoulders, adding modesty and shape. The saya, a floor-length skirt characterized by bold stripes or flowers, was wrapped around the waist securely, with cotton petticoats (enaguas) providing volume. The appearance was also completed by accessories, such as a peineta comb in the hair, a rosary or crucifix necklace, coral beads, and beautifully styled velvet slippers or delicate sandals. Hair was usually styled into a neat bun or chignon, frequently with a ribbon or lace trim, echoing a combination of Spanish colonial influence and local expressions of femininity.

SOURCES:

- Coo, Stephanie Marie R. 2019. Clothing the Colony: Nineteenth-Century Philippine Sartorial Culture, 1820-1896. Ateneo De Manila University Press.

- Camagay, Maria Luisa T. 2018. Unraveling the Past: Readings in Philippine History.

- De La Costa, Horacio. 1992. Readings in Philippine History: Selected Historical Texts Presented with a Commentary.

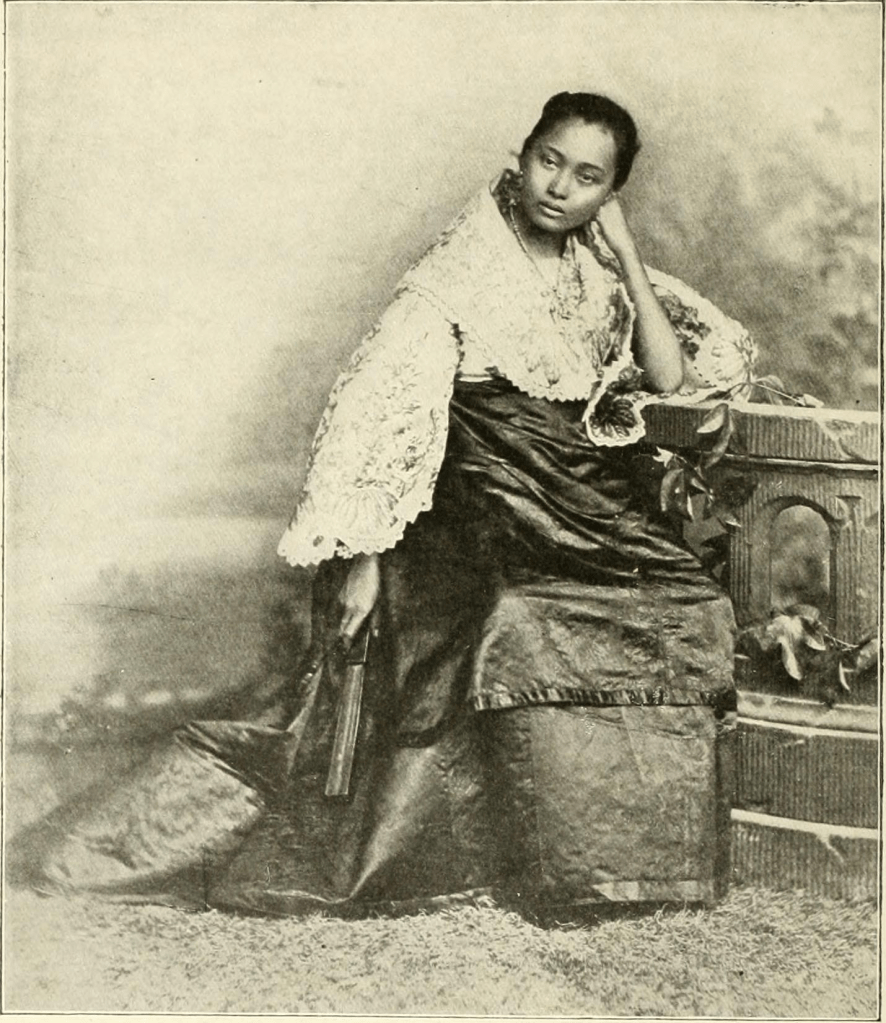

Traje de Mestiza (1880)

Words by: Ivan Beley

In the 1800s, formal occasions in the Philippines typically called for European-style attire, particularly for women who donned bustle skirts inspired by Victorian England. However, as nationalist feelings began to emerge in the mid-1880s, the prevalence of this fashion started to wane. The Traje de Mestiza—often referred to today as the Maria Clara dress—slowly supplanted European fashions and gained wide acceptance among Filipino women from various social backgrounds. This garment eventually came to represent Filipino identity, especially during the nationalist movement and subsequent revolution.

Historically, the native women had worn saya (wrap-around skirts) and baro (blouses) crafted from locally sourced materials such as cotton, sinamay, or lace for centuries. By the 1880s, the Traje de Mestiza evolved to include flowing sleeves that became progressively wider and more structured as embroidery techniques advanced. These sleeves transitioned from the delicate angel shape to bell forms and ultimately developed into the puffy butterfly sleeves popularized by the 1890s—a style that continued to undergo refinements over the years.

Given that the baro was often made from sheer fabrics like nipis, women frequently wore embroidered or trimmed undershirts such as the camiseta, camisón, and corpiño for added comfort and modesty. Wealthier women sometimes opted for luxurious imported materials like Swiss cañamoso for their undergarments.

As the designs of the baro shortened and the fabrics became increasingly delicate, accessories such as the pañuelo—a lace or embroidered kerchief—gained prominence for both practical and ornamental purposes. Often starched to hold a graceful appearance, the way the pañuelo was styled or pinned turned into a personal and fashionable expression.

Upper garments, particularly the baro, were a reflection of a woman’s skill and social standing, often passed down through generations as cherished family heirlooms. Caring for these garments was a meticulous process, especially due to the delicacy of materials like piña and sinamay. Each time the garments were worn, they required careful disassembly, washing, pressing with traditional wooden tools like the prensa de paa, and reassembly.

A notable example of this craftsmanship is a preserved piña baro from 1876 to 1900, held at the Museo del Traje. This piece showcases intricate embroidery and design elements characteristic of the post-1850s fashion, exemplifying the dedication, creativity, and identity inherent in these traditional garments.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

This ensemble represents the traje de mestiza worn by upper-class women in the 1880s. The outfit featured a sheer, fitted baro (blouse) made from fine piña or jusi fabric, with elbow-length butterfly sleeves and delicate embroidery, often in lace or calado openwork. Draped over the shoulders was a stiffened pañuelo, a triangular shawl typically made of starched lace, piña, or jusi, and richly decorated with floral embroidery. The saya, a high-waisted and full-length skirt, was deeply pleated and worn over several layers of cotton or lace enaguas (petticoats) to create volume and structure. Over the saya, women often wore a sobrefalda, a decorative outer skirt or overskirt made from silk or brocade, adding contrast and elegance to the ensemble.

To complete the look, accessories such as fans, parasols, coral or gold jewelry, and embroidered slippers or chinelas were commonly used. The hair was neatly tied in a bun and adorned with a peineta (ornamental comb), and a mantilla was sometimes added, especially when attending church or formal social gatherings. Together, these elements created a refined and stately silhouette that reflected both colonial influence and Filipino identity.

SOURCES:

- Coo, Stephanie Marie R. 2019. Clothing the Colony: Nineteenth-Century Philippine Sartorial Culture, 1820-1896. Ateneo De Manila University Press.

- Camagay, Maria Luisa T. 2018. Unraveling the Past: Readings in Philippine History.

- De La Costa, Horacio. 1992. Readings in Philippine History: Selected Historical Texts Presented with a Commentary.

- The Philippine Folk Life Museum Foundation (n.d.) Traje de Mestiza

- Sison, S. (2019) Here’s Everything You Need to Know About the Filipiniana Attire. Preview PH

- San Jose, C. (2019) The terno is back from the baul. Now what? Nolisoli PH.

- Piguing, and Ken Tatlonghari. 2021. “The ‘Mixed’ Dresses’ Development.” Renacimiento Manila. February 26, 2021. Accessed May 11, 2025. https://renacimientomanila.org/2021/02/21/traje-de-mestiza-devt/.

Mestizo Attire (Male) 1840s

Words by: Ivan Beley

During the 1840s, fashion among the Principalia underwent a significant transformation, influenced by colonial dynamics and local social aspirations. A prominent development during this period was the embrace of sheer untucked shirts known as Barong Mahaba, crafted from luxurious native materials like piña and jusí. These garments, often adorned with intricate embroidery, were typically paired with striped trousers and stylish accessories. Aside from showcasing their wealth and status, wearing these outfits aligned with Western ideals of social distinction.

Later on, men’s fashion began to diversify based on different occasions. Western suits became the norm for work and education, while the baro was the preferred choice for church and festive events. Over time, the baro evolved into shorter, more fitted styles decorated with embroidered patterns, resembling what we now know as the modern Barong Tagalog. Along the way, color palettes transformed from vibrant hues to more muted shades.

With the rise of social mobility and a growing middle class, traditional class distinctions in fashion began to blur. While Indios and Mestizos adopted European styles, the elite still highlighted their luxury through elaborate embroidery and high-quality fabrics. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 also played a pivotal role, exposing locals to global fashion trends and speeding up these changes. Ultimately, the fashion of elite native men showcased a blend of cultural adaptation and social assertion, even as the precise origins of the Barong Tagalog remain somewhat unclear due to limited historical documentation.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

This is a typical clothing of an Upper Class Male Mestizo in the 1840s that showcased a blend of Filipino Heritage and Spanish Colonial Styles. This emphasizes both comfort and formality. He would often don a Barong Mahaba, a long-sleeved, hand-embroidered shirt crafted from fine piña cloth, which reached the hips. This was elegantly paired with Calzones Rayados, tailored striped trousers in the Spanish fashion. A silk or muslin cravat was loosely tied around his neck, adding an element of sophistication, while a Sombrero de Paja, a braided straw hat, provided both shade and a finishing touch when outdoors. On his feet, he alternated between low-heeled leather slippers and imported European lace-up shoes based on the occasion. Accessories like a silver-mounted walking cane, a pocket watch, and a handkerchief were subtle yet effective indicators of his status, education, and social ambitions, marking the outfit as a distinct representation of elite mestizo identity within colonial society.

SOURCES:

- Coo, Stephanie Marie R. 2019. Clothing the Colony: Nineteenth-Century Philippine Sartorial Culture, 1820-1896. Ateneo De Manila University Press.

- Camagay, Maria Luisa T. 2018. Unraveling the Past: Readings in Philippine History.

- De La Costa, Horacio. 1992. Readings in Philippine History: Selected Historical Texts Presented with a Commentary.

Reform and Revolution

Words by: Ivan Beley

The 19th century was marked by the rise of Filipino consciousness and nationalist ideals that challenged Spanish colonial rule in the Philippines. After nearly three centuries of oppression, new economic trends and the influence of liberalism and nationalism from Europe and America sparked calls for reform.

The reform movement began in early 19th-century Spain after the resistance to the invasion of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1810, and the passing of the Cadiz Constitution in 1812. When the Iberian Peninsula faced a time of political upheaval, including the loss of colonies in America, and the Carlist War from 1834 to 1839, following the La Gloriosa Revolución of 1868, Liberal Reform was then introduced, resulting in the temporary dethronement of Queen Isabel II. The opening of the Philippines to international trade in the 1830s and the launch of the Suez Canal in 1869 facilitated the influx of ideas about liberty, equality, and fraternity, encouraging Filipinos to advocate for rights and reforms.

The ilustrados, an educated class, formed the backbone of a movement, which, especially after the Cavite Mutiny in 1872, which led to the martyrdom of three secular Filipino priests—Fr. Mariano Gomez, Fr. Jose Burgos, and Fr. Jacinto Zamora—collectively known as GomBurZa. The movement called the Propaganda Movement was formed in 1880-1885 to seek representation in the Spanish Cortes and legal equality for the natives.

However, the efforts of the reformists faced persecution, leading to censorship and exile. Frustration among the masses, particularly the lower class, grew, and revolutionary sentiments began to spread. On July 7, 1892, the Kataas-Taasan, Kagalang-galangan, Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (Katipunan) was founded at 72 Calle Azcaraga. This organization aimed for total independence from Spain, operating secretly and disseminating revolutionary propaganda.

As tensions escalated, the execution of José Rizal ignited a surge of public support for independence. Key figures such as Andres Bonifacio played crucial roles in driving the revolution, which culminated in the declaration of independence on June 12, 1898. The transition from seeking reform to pursuing revolution was fueled by widespread disillusionment with colonial liberalism, significantly altering the course of Philippine history.

SOURCES:

- Dumol, Paul A., and Clement C. Camposano. 2018. The Nation as Project. Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines: Vibal Group Inc.

- Camagay, Maria Luisa T. 2018. Unraveling the Past: Readings in Philippine History.

- Guerrero, León Ma. 2007. The First Filipino: A Biography of José Rizal.

- De La Costa, Horacio. 1992. Readings in Philippine History: Selected Historical Texts Presented with a Commentary.

- Tan, Samuel K. 2008. A History of the Philippines. UP Press.

- Francia, Luis H. 2013. History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos. Abrams.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. 1990. History of the Filipino People. 8th ed. Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines: R.P. Garcia Publishing Co.

- Schumacher, John N., S.J. 1991. The Making of a Nation: Essays on Ninteenth~Century Filipino Nationalism. Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines: Ateneo De Manila University Press.

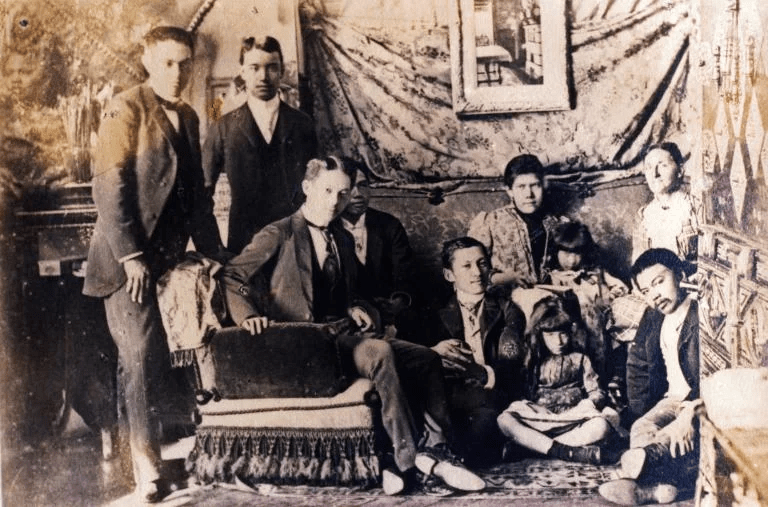

Ejército Filipino (Army of the Philippine Republic)

Words by: Diego Magallona

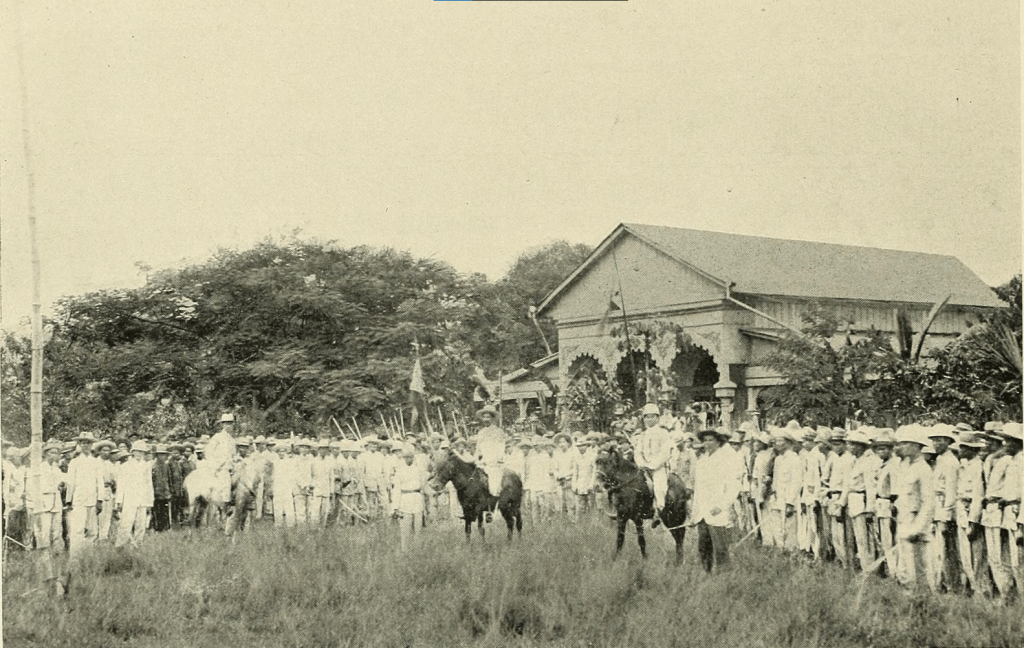

The Philippine Army during this period had several names, often translated as the “Philippine Revolutionary Army” or “Philippine Republican Army.” In primary sources, “Hocbong Tagapagbagong Puri,” “Hocbo ng Panghihimagsic” and “Ejército Revolucionario” (“Revolutionary Army” in Tagalog and Spanish, respectively) are some of its names, but the Army was more commonly referred to in documents as simply “Ejército Filipino” – Philippine Army.

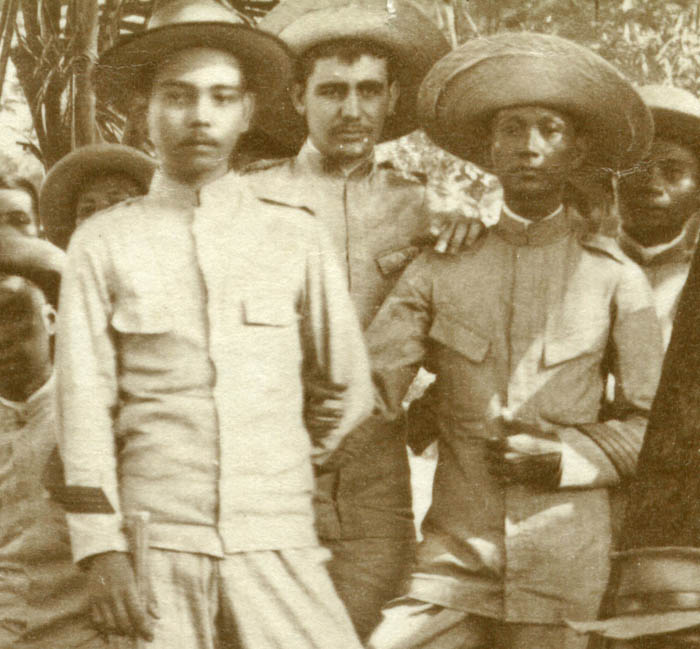

The Philippine Army can trace its origins to the Tejeros Convention of 22 March 1897, where the Magdiwang and Magdalo councils of the Katipunan organized a revolutionary government and formal army organization to take charge of the Revolution against Spain. In practice, they remained an irregular peasant army, dressed mostly in civilian clothing and using whatever weapons they could get. This began to change in 1898 with the return of General Aguinaldo and the collapse of Spanish resistance across the archipelago. The Filipino revolutionaries were able to acquire plenty of Spanish weapons and uniforms from surrendering and defecting Spanish Army units, which they readily incorporated into their forces.

From 30 July 1898, the Ejército Filipino officially adopted Spanish military doctrines and tactics, and in the months leading up to the Filipino-American War, its soldiers were trained in the Spanish style. The Philippine Army was divided into multiple corps, including the Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery, Engineers, Signals, Medical and Pharmaceutical, and Military Clergy. Most units of the Army were Infantry, but they did have limited numbers of Cavalry and Artillery, as well as a competent Corps of Engineers that constructed the Army’s trenches and other fortifications.

However, while the Philippine Army was beginning to look like a modern military, it still lacked the experience, organization, and logistics to effectively wage a modern war. These weaknesses would prove disastrous during the Filipino-American War. The Ejército Filipino made a valiant and costly effort to defend the Philippine Republic from the invading United States using both conventional and guerrilla warfare tactics, but by 1901 Pres. Aguinaldo and most of his government had been captured, and the last generals of the Republic surrendered with their battalions by 1902.

SOURCES:

- Angeles, Jose Amiel. As Our Might Grows Less: The Philippine-American War in Context. PhD Dissertation, University of Oregon. 2014.

- Guevara, Suplicio (ed.). The Laws of the First Philippine Republic (The Laws of Malolos), 1898-1899. Manila: National Historical Commission, 1972.

- Taylor, John R.M (ed.). The Philippine Insurrection Against the United States. Vol. 3-4. Pasay City: Eugenio Lopez Foundation, 1971

Infantry Officer’s Service Uniform, Philippine Republican Army, 1899

Words by: Diego Magallona

In its effort to professionalize the Philippine Army, the Revolutionary Government introduced new uniform regulations for the officer corps, formalized in December of 1898. Among these new regulations was the official adoption of the “Mambisa” military tunic or jacket, possibly named in honor of “Mambises” – Cuban freedom fighters. This uniform’s design was unique to the Philippine Army, and not a copy of any Spanish or other foreign pattern. The mambisa was worn mostly by officers of the Philippine Army (and rarely by enlisted men as well) during the Filipino-American War.

Philippine Army regulations described the mambisa as a jacket with a standing collar, 2 vertically-oriented chest pockets with buttoned pocket flaps, and pockets at the bottom of the jacket. The Filipino mambisa uniform was also distinguished by two vertical pleats that ran from the shoulders to the bottom of the jacket.

While most Philippine Army mambisa uniforms were made with striped rayadillo fabric, Army regulations specified other variations of the mambisa made with different fabrics: mambisa blanca (white), de kake (khaki), de guingon (dark blue), and de cañamo (greyish/natural hemp).Some collectors and historians have referred to this Philippine uniform as the “Norfolk”-style Filipino jacket because of certain similarities to that English jacket design, particularly the vertical pleats. However, there is no evidence that the English Norfolk jacket served as inspiration for the design of the mambisa. It is more likely that the Guayabera tunic (of Cuban origin) inspired the design. Aside from the Cuban term “mambisa” being used in Philippine Army regulations, Gen. Jose Alejandrino in one of his letters described the new uniform as being “in the shape of the mambisa cubana.”

EXHIBIT ITEM:

This uniform is an example of Traje De Diario (service dress) worn by an infantry officer of the Ejército Filipino. The officer wears a Mambisa De Rayadillo jacket with scarlet epaulets that identify him as an officer of the Infantry, with two gold stars denoting the rank of Teniente Coronel (Lieutenant Colonel). The sword/pistol belt is worn inside the jacket, and the weapons are attached to the belt via slits on the sides of the jacket. He is wearing regulation trousers for officers of the Infantry, made of dark blue guingon fabric with two stripes of white piping running down the sides. Unlike enlisted soldiers, the officers were expected to wear leather boots. In the field, infantry officers usually wore sombreros (straw hats), but they would wear capacetes (sun helmets) and gorra (peaked caps) as well.

SOURCES:

- Alejandrino, Jose. La senda del sacrificio: episodios y anecdotas de nuestras luchas por la libertad. Manila: 1933

- Gobierno Revolucionario, 1898. “Decree of November 25, 1898, regulating Army Uniforms.” In The Laws of the First Philippine Republic (The Laws of Malolos), 1898-1899, compiled and edited by Suplicio Guevara. Manila: National Historical Commission, 1972.

Corporal’s Uniform, Manila Battalion, Philippine Republican Army, 1899

Words by Diego Magallona

The regular forces of the Philippine Army were organized into several battalions, some numbered or specialized but most named after their province of origin. The Batallón Manila was mustered in the town of Malabon (then a part of the Province of Manila) in 1898. They were led by Colonel Cipriano Pacheco and were part of the 4th Military Zone of Manila, under the command of Brigadier General Pantaleon Garcia. Both commanders were members of the Katipunan and veterans of the revolution against Spain.

The Batallón Manila was considered one the most well-trained battalions of the Philippine Army because many among its ranks were Filipino veterans of the Spanish Army who had defected, mostly from the 73rd Infantry Regiment and the Carabinero customs guards. The Battalion saw its fiercest fighting from the 25th-27th of March 1899 during the battles to defend the Philippine Republic’s capital of Malolos. On the 25th of March they managed to check the advance of Gen. Loyd Wheaton’s 2nd Oregon and 3rd Infantry Regiments at the Tuliahan River, which prevented Wheaton’s brigade from crossing the river at Tinajeros and Malabon and allowed the Manila Battalion to retreat in good order and fight again in the following days.

Their valor and discipline earned the battalion the moniker of “El Famoso” – “the famous” Manila Battalion – on both the Filipino and American sides. At some point in 1899, the Batallón Manila donned red trousers, signifying that they were among the elite units of the Philippine Army. The last major engagements of the Manila Battalion were fought around Arayat, Pampanga in October 1899. After the war, some of its surviving members, including Col. Pacheco and Gen. Garcia, joined the Asociación de los Veteranos de la Revolución.

EXHIBIT ITEM:

The uniform on display represents a Cabo (Corporal) of the Manila Battalion as described in US Army reports in October of 1899. This soldier wears a sombrero made of straw, with a black oilcloth band where the words “Bón. Manila” are written in gold-colored paint. He wears a Spanish Army Guerrera de rayadillo tunic and red trousers. On the cuffs of his uniform are the gold and white chevrons of a corporal. Like most Filipino soldiers, he is barefoot. He is also equipped with Spanish Army leather accoutrements for the Remington rifle; these could be complete or incomplete, as Filipino units tended to divide the ammunition pouches of a single set to equip multiple soldiers.

SOURCES:

- Garcia, Pantaleon. Maikling Kasaysayan ng Himagsikan Sa Pilipinas. Manila: Dalaga, 1930.

- Rivera, Jose Maria. “Un batallon que se deja diezmar pero no se rinde,” La Vanguardia, 10 November 1934.

- Wells, Harry Laurenz. The War in the Philippines. San Francisco: Sunset Photo-engravers, Printers, Publishers, 1899.

- US War Department, Annual Reports of the War Department for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899: Report of the Major-General Commanding the Army in Three Parts – Part 3. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899.

Leave a comment